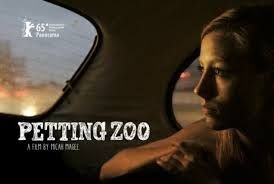

I’m only three films into watching ’52 films directed by women’ and I have seen my first modern masterpiece. Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you ‘Petting Zoo’ by the prodigiously talented writer-director and mother of three, Micah Magee.

Mother of three? Yes, I know – it’s an irrelevance. You don’t ask how many children Martin Scorsese has fathered (from how many different wives) or why he didn’t allow his daughter to throw pies in the house. Sometimes being the progeny of a film director is no help at all – ask Jake Scott, son of Ridley Scott, who helmed Plunkett and Maclaine (1999). Jake’s only other film is Welcome to the Rileys (2010) - I haven’t heard of it either.

But Petting Zoo is about unwanted pregnancy, a feeling Magee has outgrown.

Now I am aware as the next film reviewer that ‘unwanted pregnancies’ – serious problem as they are - are becoming a movie cliché. Why, I have only just recently seen Paul Weitz’s Grandma, in which Lily Tomlin’s titular character helps her granddaughter scrape together $640 for a ‘procedure’. And, for schizz, there is Juno.

But Magee is a real moviemaker – a natural converter of experience into meaningful storytelling. Her protagonist, Layla (Devon Keller) is on, if not the lowest economic rung, the one just above it. She doesn’t have a car; you can’t get any poorer than that.

Layla is a seventeen year old San Antonio Texas High School student who has succeeded in getting a scholarship at the University of Austin. When she expresses a small gesture of surprise that her bong-chugging boyfriend, who, if not a total drug head, then the rung just above it, wants to move to Austin with her and support her, he gets all uppity and sulks off to the next room, where the pipe is at.

Layla loves her grandmother, who is naturally pleased for her, but exists in a whole different astral plane to her uncle who is busy selling off the little they have – he asks his mother for twenty dollars and settles for five. He does, however, give Layla a lift to work at a call centre, where she has a three word maximum when it comes to engaging with customers who are asked for their zip code. Having dumped her man and been told by her best friend, ‘can you not have a boyfriend for five minutes’, Layla sees a handsome boy at a concert. She abides by her friend’s request and sleeps in the car while her friend parties on.

But then Layla discovers that she’s pregnant. This puts her college application – her whole future – in jeopardy.

Petting Zoo is not one of those heart-warming Hollywood movies that milks tears from vulnerable audience members. It is honest. Not depressingly so, but enough for you to believe in it on a scene-by-scene basis. The only time it deviates from realism is during a pre-sex scene when Layla takes off her shirt (her back to camera – she’s just seventeen) and a boy is in his underpants. The kid doesn’t have an erection. This is a low-budget, independently produced, part crowd-funded movie. It has a European vibe (and some German financing). So you wonder why the director couldn’t show a boy being sexually aroused. I know the answer: in America, a hot dog inside the ‘y’ fronts is taboo. But it have the unfortunate effect of reminding me, albeit briefly – pun intended – that I was watching a movie.

I don’t want to describe how Layla deals with her pregnancy, but each scene follows the last in a matter-of-fact way. There is at least one extraordinary, but believable, image of Layla in bed with her grandmother, and one shocking one after a family row gets out of hand. This is also one of the few films to feature a Denny’s restaurant, not in a product placement sort of way. Cineastes will know that Quentin Tarantino wanted to film in a Denny’s but was refused permission. The chain naturally didn’t want to make the same mistake twice.

The economy of storytelling is what really impresses you, notably when we are introduced to Layla’s parents. Layla’s father is so controlling – ‘you’re going to have this baby and we’re going to deal with it as a family’ – that you understand both why Layla doesn’t live at home and why she responds in the way that she does – one of the film’s few moments of humour. There is a terrific scene as Layla gets a driving lesson and a ‘what the heck’ moment when her ex-boyfriend and family show up to undertake some damage limitation.

Magee instructed her lead actress not to judge the character of Layla. She certainly has some lapses, but then we all do. These add to the realist vibe. Also, and let’s not forget, she’s just seventeen. The finale is as unsentimental as it is possible to be about something horrific. Yet, there is hope. Magee had to re-shoot the final scene, making a particular stylistic choice to underline that things might get better.

In the opening scene, we hear how a boy got hold of his father’s gun. This isn’t a film where a gun introduced in Act One goes off in Act Three. It illustrates how children in the world Layla inhabits aren’t treated as kids. One of the other humorous scenes involves two young children shielded from an adult conversation yet watching a horror film. There’s not much control of ‘inappropriate material’ either.

Watched on Saturday 18 October, 18:15, Cine Lumiere, South Kensington – London Film Festival screening. Third of ’52 films directed by women’. With thanks to Cine Lumiere and LFF Box Office staff