Long before there was a Federal Bureau of Investigation, there was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Founded in the early 1850s by Scottish immigrant Allan Pinkerton, the “Pinkertons” were the nation’s first and most prominent private police force. They’re best known for hunting down Old West outlaws and train robbers, but they also worked as presidential security, intelligence operatives and—most controversially—as management muscle during labor strikes. Check out 10 little-known facts about the detective agency that helped usher in the modern era of law enforcement.

Its founder became a detective by accident.

In 1842, Allan Pinkerton immigrated to the Chicago area and opened a cooperage, or barrel-making business. His detective career began just five years later, when he stumbled upon a band of counterfeiters while scrounging for lumber on an island in the Fox River. The Scotsman conducted informal surveillance on the gang, and was hailed as a local hero after he helped police make arrests. “The affair was in everybody’s mouth,” he later wrote, “and I suddenly found myself called upon from every quarter to undertake matters requiring detective skill.” Pinkerton soon won a gig as a small town sheriff. He went on to work as Chicago’s first police detective and as an agent for the U.S. Post Office. Around 1850, he opened the private investigation firm that became the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

The Pinkertons inspired the term “private eye.”

The Pinkerton agency first made its name in the late-1850s for hunting down outlaws and providing private security for railroads. As the company’s profile grew, its iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.

The Pinkerton agency first made its name in the late-1850s for hunting down outlaws and providing private security for railroads. As the company’s profile grew, its iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.

They hired the nation’s first female detective.

In 1856, 23-year-old widow Kate Warne walked into Pinkerton’s Chicago office and requested a job as a detective. Allan Pinkerton was hesitant to hire a female investigator, but he gave in after Warne convinced him that she could “worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.” True to her word, Warne proved to be an expert at working undercover, once busting a thief by cozying up to his wife and convincing her to reveal the location of the loot. During another case, she got a suspect to feed her crucial information by disguising herself as a fortune-teller. Pinkerton would later list Warne as one of the best investigators he ever hired. Following her death in 1868, he even had her buried in his family plot.

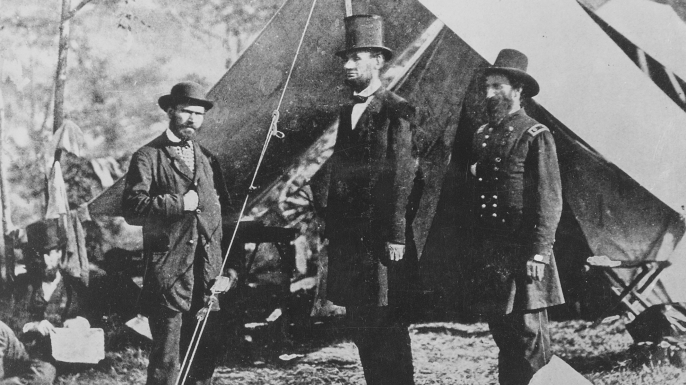

The Pinkertons may have foiled an assassination attempt on Abraham Lincoln.

Shortly before Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration in March 1861, Allan Pinkerton traveled to Baltimore on a mission for a railroad company. The detective was investigating rumors that Southern sympathizers might sabotage the rail lines to Washington, D.C., but while gathering undercover intelligence, he learned that a secret cabal also planned to assassinate Lincoln—then on a whistle-stop tour—as he switched trains in Baltimore on his way to the capital.

Pinkerton immediately tracked down the president-elect and informed him of the alleged plot. With the help of Kate Warne and several other agents, he then arranged for Lincoln to secretly board an overnight train and pass through Baltimore several hours ahead of his published schedule. Pinkerton operatives also cut telegraph lines to ensure the conspirators couldn’t communicate with one another, and Warne had Lincoln pose as her invalid brother to cover up his identity. The president-elect arrived safely in Washington the next morning, but his decision to skirt through Baltimore saw him lampooned and labeled a coward in the press. Meanwhile, none of the would-be assassins was ever arrested, leading some historians to conclude that the threat may have been exaggerated or even invented by Pinkerton.

They spied for the Union Army during the Civil War.

Allan Pinkerton was a staunch abolitionist and Union man, and during the Civil War, he organized a secret intelligence service for General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Operating under the name E.J. Allen, Pinkerton set up spy rings behind enemy lines and infiltrated southern sympathizer groups in the North. He even had agents interview escaped slaves to glean information about the Confederacy. The operation produced reams of intelligence, but not all of it proved accurate. A famous misstep came during 1862’s Peninsula Campaign, when Pinkerton reported that the Confederate forces around Richmond were more than twice their actual size. McClellan believed the faulty intel, and despite outnumbering the rebels by a large margin, he delayed his advance and made repeated calls for reinforcements.

The Pinkertons created one of the world’s earliest criminal databases.

One of the many ways the Pinkertons revolutionized law enforcement was with their so-called “Rogues’ Gallery,” a collection of mug shots and case histories that the agency used to research and keep track of wanted men. Along with noting suspects’ distinguishing marks and scars, agents also collected newspaper clippings and generated rap sheets detailing their previous arrests, known associates and areas of expertise. A more sophisticated criminal library wouldn’t be assembled until the early 20th century and the birth of the FBI.

The Pinkertons warred with Jesse James and his gang.

During the era of frontier expansion, express companies and railroads often employed the Pinkertons as Wild West bounty hunters. The agency famously infiltrated the Reno gang—perpetrators of the nation’s first train robbery—and later chased after Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch. The Pinkertons usually got their man, but in the 1870s, they spent months engaged in a fruitless hunt for the bank robbers Jesse and Frank James. One of their agents was murdered while trying to infiltrate the brothers’ Missouri-based gang, and two more died in a shootout.

The hunt came to a bloody end in 1875, when the Pinkertons launched a raid on the James brothers’ mother’s house in Clay County, Missouri. Frank and Jesse were nowhere to be found—they’d been tipped off—but the Pinkertons got into an argument with their mother, Zerelda Samuel. During the standoff, a member of the detectives’ posse tossed an incendiary device through Samuel’s window, blowing part of her arm off and killing the James brothers’ 8-year-old half brother. The botched raid turned public opinion against the Pinkertons. After seeing his detectives denounced as murderers in the papers, Allan Pinkerton reluctantly called off his war against the James gang. Jesse would go on to elude the authorities for another seven years before being killed by an assassin’s bullet in 1882.

They played a role in 1892’s infamous Homestead Mill Strike.

Along with their exploits in the Wild West, the Pinkertons also had a more sinister reputation as the paramilitary wing of big business. Industrialists used them to spy on unions or act as guards and strikebreakers, and detectives clashed with workers on several occasions. During an 1892 strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, the Carnegie Steel Company paid some 300 Pinkertons to act as security at its mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania. After arriving at the plant on river barges, the agents squared off with thousands of striking workers in an all-day battle waged with guns, bricks and even dynamite. By the time the outnumbered Pinkertons finally surrendered, at least a dozen people were dead and several more wounded. The fallout from the melee crippled the steel union, but many also branded the Pinkertons as “hired thugs,” leading several states to pass laws banning the use of outside guards in labor disputes.

The Pinkertons were once larger than the U.S. Army.

After Allan Pinkerton died in 1884, control of his agency fell to his two sons, Robert and William. The company continued to grow under their watch, and by the 1890s, it boasted 2,000 detectives and 30,000 reserves—more men than the standing army of the United States. Fearful that the agency could be hired as a private mercenary army, the state of Ohio later outlawed the Pinkertons altogether.

The agency still exists today.

By the early 20th century, the Pinkertons’ crime fighting duties had largely been absorbed by local police forces and agencies like the FBI. The company lived on as private security firm and guard service, however, and still operates today under the shortened name “Pinkerton.”