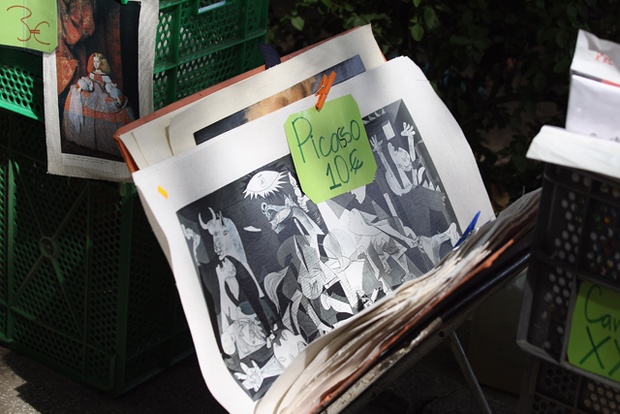

You already know Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica is among his most revered works, but do you know how and why he created the anti-war masterpiece?

1. GUERNICA WAS A COMMISSIONED PAINTING.

As the 1937 World’s Fair approached, members of Spain’s democratic government wanted the Spanish pavilion at Paris’ International Exposition Dedicated to Art and Technology to feature a mural that would expose the atrocities of Generalissimo Francisco Franco and his allies. Naturally, these organizers set their sights on one of Spain’s most celebrated painters, Pablo Picasso, who had first gained recognition in the 1910s with his adoption of cubist artistic expression.

2. PICASSO HADN’T BEEN TO SPAIN IN OVER THREE YEARS.

Picasso didn’t have to go far to work on a piece for the Paris exhibition—he had lived in France since 1904. An expat who was vocal about his opposition to the militant autocracy of his home country, Picasso crafted the tribute to the war-torn Spanish city without having set foot within the nation’s borders since 1934. He would never return to Spain.

3. FRANCO’S FORCES BLAMED THE BOMBING DEPICTED IN THE PAINTING ON THEIR RIVALS.

Picasso’s painting depicts the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937. Franco’s German and Italian allies in the Spanish Civil War carpet-bombed Guernica, a stronghold of Republican opposition to Franco’s Nationalists, for hours. Casualty estimates vary from 200 to 1000 deaths. To make matters worse, Franco and his allies blamed the horrific attack on Republican forces.

4. AN ARTICLE IN THE TIMES INSPIRED PICASSO.

Picasso didn’t witness the Guernica atrocities firsthand, but he was deeply moved by a report of the event written by South African-British journalist George Steer for The Times. The article, titled, “The Tragedy of Guernica: A Town Destroyed in Air Attack: Eye-Witness’s Account,” was attributed in print to “Our Special Correspondent.”

5. HE BEGAN WORKING ON THE PAINTING AT THE LAST MINUTE.

Getty Images

Picasso was so affected by Steer’s Guernica story that he scrapped all pending plans to devote himself to the pavilion mural. The artist began work on what would be one of his earliest politically inclined pieces on May 1, 1937, approximately three weeks before the scheduled launch of the exhibit. Guernica was not completed until early June, about two weeks after the pavilion opened.

6. PICASSO SIMULTANEOUSLY PUT TOGETHER ANOTHER CRITIQUE OF FRANCO.

The fact that Picasso cranked out what is now known as one of the most famous paintings of the 20th century in just over a month is impressive enough in its own right, but Guernicawasn’t even the sole focus of the artist’s attention during this time. In January 1937, Picasso had published a set of etching and aquatint prints, collectively titled The Dream and Lie of Franco. On June 7 of the same year, around the same time that he delivered Guernica to the Spanish pavilion, Picasso added a second batch of images to The Dream and Lie of Franco.

7. AN EARLY VERSION OF THE PAINTING WAS MORE EMPOWERING.

Unsurprisingly, Guernica evolved between its inception and completion. One of Picasso’s earliest drafts of the painting included a raised fist, a universal symbol of solidarity in resistance to oppression. Opponents of Franco’s reign had embraced the emblem during the Spanish Civil War. Picasso depicted the fist empty-handed at first, then grasping a sheaf of grain. Ultimately, he deleted the image altogether.

8. ANOTHER STAGE OF GUERNICA INVOLVED COLOR.

Guernica is one of history’s most recognizable grayscale paintings, but at one point during the piece’s development, Picasso entertained the idea of adding color to the project. He included a red teardrop sprouting from a crying woman’s eye, as well as swatches of colored wallpaper. None of these elements made the final cut.

9. PICASSO REFUSED TO TALK ABOUT THE PAINTING’S SYMBOLISM.

Scholars have long tried to decode the significance of the symbols in Guernica, especially the horse and bull figures. Naturally, Picasso was probed to explain the use of these creatures in his painting. He never offered anything more revelatory than “This bull is a bull and this horse is a horse,” adding, “If you give a meaning to certain things in my paintings it may be very true, but it is not my idea to give this meaning. What ideas and conclusions you have got I obtained too, but instinctively, unconsciously. I make the painting for the painting. I paint the objects for what they are.”

10. EARLY REVIEWS OF THE PAINTING WEREN’T ALL POSITIVE.

Getty Images

Today, Guernica is celebrated as one of Picasso’s premiere achievements. But it wasn’t always hailed as a masterpiece. Among the piece’s leading detractors were American critic Clement Greenberg (who called Guernica “jerky” and “compressed”), French painter and communist Edouard Pignon (who maligned the painting for its misplaced political message and lack of empathy for the working class), French philosopher Paul Nizan (who shared Pignon’s sentiments, and further called Guernica a product of the bourgeoisie mentality), and American abstract painter Walter Darby Bannard (criticizing in particular the painting’s counterintuitive scale).

11. NAZI GERMANY TOOK POTSHOTS AT GUERNICA.

Due to both Guernica’s antifascist message and Adolf Hitler’s personal aversions to modern art, the official German guidebook for Paris’s International Exposition recommended against visiting Picasso’s piece, which it called “a hodgepodge of body parts that any four-year-old could have painted.”

12. YEARS LATER, GERMANY USED THE PAINTING IN A MILITARY CAMPAIGN.

Apparently misunderstanding the nature of Guernica and its antiwar stance, the German military used the painting in an ill-conceived recruiting advertisement in 1990. The ad featured the slogan, “Hostile images of the enemy are the fathers of war.”

13. THE PAINTING INSPIRED A PICASSO EXCHANGE WITH A GESTAPO OFFICER.

Almost as famous for his biting wit as he was for his artistic prowess, Picasso once treated a German Gestapo officer to a sharp rejoinder in reference to the painting’s depiction of the atrocities of fascism and war. When asked by an officer about a photo of the painting, “Did you do that?” Picasso is said to have replied, “No, you did.”

14. THE PAINTING WAS VANDALIZED BY AN ANTIWAR ACTIVIST.

Getty Images

At one point its long residency at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, Guernica suffered an act of politically-charged defacement. In 1974, Tony Shafrazi—who would later become a respected art dealer—spray-painted the words “KILL ALL LIES” over the painting. Upon his apprehension by museum security, Shafrazi famously shouted, “Call the curator. I am an artist.”

15. THE PAINTING WAS COVERED UP DURING A SPEECH MADE BY COLIN POWELL.

From 1985 to 2009, the United Nations adorned the entrance of its Security Council with a tapestry reproduction of Guernica. In February 2003, then-Secretary of State Colin Powell delivered a televised speech on site at the UN, testifying in favor of America’s imminent declaration of war on Iraq. A large blue curtain covered the tapestry during Powell’s speech.

Conflicting reports attributed the decision to obscure Guernica both to journalists thinking the violent imagery would be unpleasant for viewers of the broadcast, and to the Bush Administration deeming the display of such a recognizable antiwar painting inappropriate for the backdrop of Powell’s promotion of military action.