A ‘wake up call for the world’: that is how one writer described the vote for Brexit, the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, with all the existing trade benefits that it gives. On 23 June 2016, 51.7% of those who voted backed a decision to ‘take back control’ from Brussels (actually, Brussels and Strasbourg – the Union has two headquarters), to ditch overly proscriptive legislation designed to assure uniformity of goods and services and to protect the national border. The vision of the United Kingdom outside the European Union is at best cloudy. Nevertheless, the result was perceived as a vote for repatriating jobs to the British people as well as homes, school places and hospital beds for Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Never mind that the United Kingdom – the South especially - relied on immigration especially from its former colonies to rebuild the country after the Second World War. Never mind the length of time it took the UK to join the European Union in the first place – its close (‘special’) relationship with the United States was seen as a barrier. Never mind the positive elements of the European Union in bringing peace to Eastern Europe in the 1990s. Never mind shared expertise in science and innovation.

Exiting the European Union – the word ‘exiting’ looks like ‘exciting’ but the process will be anything but – will, we are told, take up to two years. After the triggering of the procedure specified in Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty to break away from the Union, members of the UK Parliament (MPs for short) will closely scrutinise proposals and counter proposals for the UK’s new relationship with the EU. As with any divorce, additional fees – in the billions of pounds - will be paid. Confidence in the UK economy has been hit. The value of the pound has dropped. We are assured that this is an expression of the will of the people, influenced by knowingly misleading advertising campaigns and slogans without substance. Strangely, it is the so-called ‘Remainers’ who are perceived as the ignorant ones. They have been dubbed as ‘Remoaners’.

The result of Britain’s ‘EU Referendum’ is as good a point to look at Britain’s national cinema. Does it contain the clues to the population’s desire to quit the EU club, to go it alone on the basis of its historic connections, educated workforce and centres of expertise, or, if you prefer, blind nationalistic faith? Is the problem a disconnection between elected officials and the people? Or has the UK population been lulled into a sense of malaise, that it thinks there is one obvious answer to the country’s problems that doesn’t involve being embroiled in military action overseas or an acknowledgement of the human rights of non-UK nationals?

British filmmakers rarely tackle such questions directly in fiction filmmaking. It doesn’t sell tickets or downloads. So the test will be what a choice of subject matter tells viewers about the British character, its self-confidence (or lack thereof) and the true source of such external constraints. Is there an archetypal protagonist, someone who expresses the aspirations of the British people and what does that person offer the world? Or is Britain a mass of contradictory impulses held together by its imperfect but functioning institutions of state? Unlike other European countries, the UK has not experienced an ideological revolution where the country has changed from a monarchy (nominally ruled by a Queen or King) to a republic (where the head of state is a President). The UK’s version of liberal democracy has evolved through a steady sequence of pacification. Vested interests have been protected through concessions that allow institutions to remain at the expense of the transfer of some power. Workers’ rights are one such concession; a National Health Service is another. The concessions have been just enough to placate a population. Only in extreme cases – the abandonment of the so-called ‘Poll Tax’ in 1992 – has UK domestic legislation proved unpalatable.

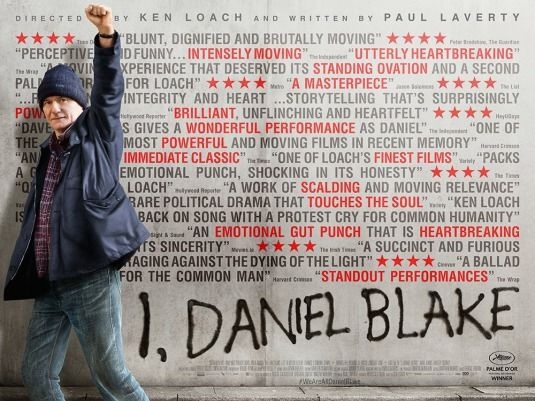

Set in Newcastle in the North of England, I, Daniel Blake, written by Paul Laverty and directed by Ken Loach, is a film that seeks to repeal sharp practices in UK welfare policy. It concerns a widowed carpenter, Daniel (Dave Johns) who is recovering from a heart attack but has been denied access to Employment and Support Allowance, what used to be termed sickness benefit. Whilst waiting to lodge to an appeal against the decision, Daniel has no choice but to apply for Job Seekers Allowance, that relies on him looking for work, even though his doctor and his hospital have recommended that he refrain from strenuous activity until his heart is functioning properly again. Whilst at a Job Centre Plus (job centre minus, more like) he encounters a single mother, Katie (Hayley Squires), moved out of London with her two children, who is late for her first appointment and faces benefit sanctions. The two become friends. However, Katie finds herself forced into the black economy to provide for her children. Daniel too is forced to make an extreme gesture.

The film is absolutely about the squeezed unwaged, working on the premise that the cost of providing welfare is too high and therefore something has to be done about it. What has this got to do with Britain’s membership of the European Union? Partly the UK’s welfare bill has increased owing to an influx of migrants requiring state assistance. However, Loach and Laverty aren’t interested in this aspect of the problem. They have taken migration out of the argument, making it purely about government policy bearing down in a cruel manner on the most vulnerable.

The film catalogues some of the extremes of UK welfare policy. Unwaged families are moved from the South to the North to avail themselves of rented accommodation at reduced costs regardless of the lack of social connection. There are sanctions against claimants who turn up late for appointments, resulting in the loss of welfare payments. In extreme cases of poverty, families and individuals are made to queue outside food banks, a Victorian concept of charity outside the welfare system. Moreover, employers are allowed to hire staff on ‘zero hour’ contracts, meaning that an employee has no guarantee of a weekly income. They could work for one hour a week or thirty-seven; there is no minimum. CV writing classes encourage job seekers to stand out; how can they do so when they can’t afford to dress well or cannot gain the experience?

The intention is to shock the poor into doing something about their lot. Does this approach work? Not if the individual has mental health issues. However, even those that don’t are alienated by the lack of help. Job seekers have to access employment opportunities using the internet, even if they don’t have a computer. If they lose social housing, they won’t be considered reliable by employers.

What the film asks for is an assumption of dignity and respectability of the welfare claimant; they are not all mass consumers of junk food working their way to their first mobility scooter. Television channels treat the poor like zoo animals gorging their way through sugary snacks and entirely uninterested in social improvement; Loach’s film is a corrective to that. Significantly, funding for his film has moved from UK’s Channel Four – home to such programmes – to the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation, paid for through the television licence fee). Channel Four has shifted in its programming from social challenge to tabloid sensationalism (‘The Killing of Tony Blair’); if you can’t beat ‘em, exploit ‘em!

The worst charge than can be levelled against Loach and Laverty’s angry and heartbreaking film is that it is propaganda. This is defined as ‘information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view’. So the test of the film is the extent to which it is biased or misleading. Do Job Centre Pluses really prevent access to benefits? Does the qualifying test for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) really ignore or downgrade medical advice?

The makers posit that the answers on Daniel’s Work Capability Assessment form (known as an ESA50) are unclear. In the first section, he is required to provide reports from his doctor, care and treatment plans. However, in the first scene in the film, as he receives his face to face assessment, the interviewer goes through the form one question at a time. For the form to be ‘unclear’, Daniel would have had to have skipped the questions, such as ‘can you lift at least one of your arms high enough to put something in your top pocket?’ (Q3). So Loach overstates the patronising nature of the Work Capability Assessment for the purpose of black comedy; Daniel is at fault for not completing the form properly. He would at least be familiar with the questions by the time the assessment takes place.

However, it is true that recovering from a heart attack does not guarantee entitlement to ESA. It isn’t one of the qualifying conditions. Even if Daniel had complained of shortness of breath, he would at most have got six points rather than the fifteen points necessary for qualification; somehow he scored 13 points. So the general argument – that the system downgrades cardiac events to non-debilitating – is correct.

There is only one scene involving a doctor; for the most part we see Daniel interact with government officials. He looks for work as an activity purely for recording in a book; when he is offered a job, he cannot take it on medical advice.

In real life, Daniel would go through a series of medical appointments to have his blood pressure checked – assuming they aren’t cancelled owing to a strain on local health services. Scenes with benefit officials would be offset by scenes with medical professionals. The film could have been about the conflict between so-called ‘health care professionals’ and medical practitioners. It isn’t. Loach wants to narrow the film down to one bureaucracy only; one man against the system, rather than one man torn between conflicting pieces of advice. Nevertheless, I would have liked a scene in a doctor’s office where Daniel asks, ‘can I work part time?’

The film offers a distorted view of the system underpinned by some factually accurate details. The general point is that the poor are forced into illegality as a result of a system that would rather pay private companies than people in need. It is malfunctioning. However, Loach and Laverty’s view of the general population is romanticised. Where are the curses against Londoners? Where is the racism? In attributing social ills entirely down to government policy, Loach perpetuates the idea that the people aren’t partly responsible for the broken system. His analysis – as evidenced by the film – is too binary.

Reviewed at Launching Films Movie Preview Network October screening event, Tuesday 18 October 2016, Vue Cinema, Piccadilly Circus, London, 16:00hrs