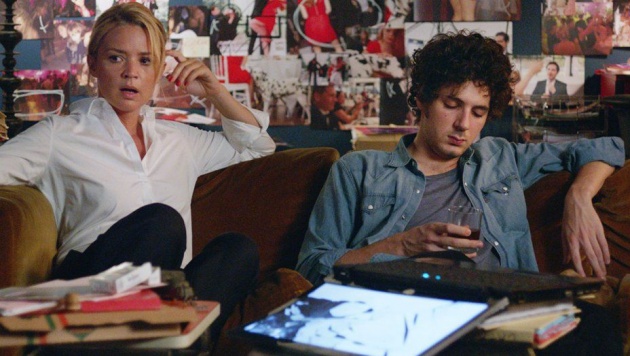

Pictured: Victoria (Virginie Efira) and Sam (Vincent Lacoste) in Victoria. Still courtesy of Ecce Films

Potentially the most over-used title of the last two years, Victoria is not just the title of a German 140 minute single take orchestrated by Sebastian Schipper or a British BBC mini-series starring Jenna Coleman as young Queen Victoria but also a French female-driven comedy written and directed by Justine Triet. Its titular heroine is Victoria Spick (Virginie Efira), a thirty-something lawyer and single mother with an intense desire to be re-ignited. While she is a professional and assured advocate, she is uninterested in sex. Yet her personal life is a revolving door of men. Her problem is that she does not ‘see’ them. To her they are neither interesting nor engaging nor even arousing. She is an equal opportunities neurotic, turning to both a male psychiatrist and a female (braided) card reader, open to any explanation of her condition. She is not stimulated by motherhood. Her two young daughters are shown early on sitting in tiny revolving chairs, dolorous, as if they had inherited their mother’s insensibility to life. As a lawyer, Victoria is not judgmental. She prefers it when her clients are guilty because (we guess) it gives her something to do, and, if she fails to get them acquitted, well, their guilt was obvious to see. But this lack of judgment dulls her emotions.

Doing not feeling

Victoria compensates for her lack of emotional engagement by doing things. In the extended pre-credits sequence – it’s so long that you forget that the credits are coming – she says farewell to her regular male child minder (they converse in English so the children cannot understand), gets an older woman to fill in and attempts multiple times to record a heartfelt but light and ‘surprised’ video greeting (of the ‘wow, you’re getting married, it’s so exciting’ variety). Victoria brings energy to every take, but each one falls short; genuine enthusiasm is something she cannot fake.

The wedding reception is a busy affair. One couple, Vincent (Melvil Poupaud) and Eve (Alice Daquet) perform a song. He performs competently, she is off-key. Eve’s cleavage-exposing red dress looks like it will fall off her at any second, embarrassed by her singing. They have barely finished when the next act takes to the stage, a man with a chimpanzee.

The real drama between Vincent and Eve occurs afterwards, but Triet does something stylistically interesting. Her camera follows Victoria from a distance and loses her in the crowd. Instead, we notice what a great time everyone is having or trying to have, because doing and feeling are two different things. Then we see Vincent on a chair facing a growling Dalmatian.

‘I said you didn’t look like a drug dealer’

At this same reception, Victoria runs into Sam (Vincent Lacoste), a one-time drug dealer whom she got acquitted who has given up his past profession – Victoria interrupts, ‘I said you didn’t look like a drug dealer’. He asks Victoria for an apprenticeship. His manner is flirtatious, yet nervous. The next day, the plot kicks in: Eve has accused Vincent of attempted murder in the act of sex; Vincent wants Victoria to defend her.

Triet constructs scenes for maximum business. For instance, Victoria arrives home to find both Sam and David (Laurent Poitrenaux) waiting for her. David, her ex, wants to see his two daughters and tells her that he’s blogging. Sam wants a job. Sam is hired to mind the children. David is sent away. Then Victoria remembers that she has a date coming round (‘Hot Paris Intellectual’). She will retire to her room. Sam will cook. Victoria allows him to use her cash card and tells him the pin. How’s that for no references?

Wrong signals

If Victoria has a flaw, it is that she sends me the wrong signals. Inviting a man into her bedroom, because daughters are outside, her date thinks this is a prelude to sex. But far from it! She wants to get to know him. She offers him a drink. He asks for ‘whiskey with sugar’. ‘That’s how I like it,’ she replies. ‘Really?’ he asks. ‘No, I just said that to make a connection.’ Poised over their drinks, the couple really have nothing to say to each other.

Victoria doesn’t want to take Vincent’s case. She has another problem. David’s blog is all about her. It is thinly disguised dirt entitled ‘Vicky Spock’ about a lawyer who slept with judges. Told by Sam about a reading David is giving, Victoria discovers a bunch of single male losers who lap up David’s blog. This is the one thing that didn’t quite ring true – I thought that most blogs written in the female voice are read mainly by women.

Portrait of apathy

The film is ostensibly about two cases: one that Victoria prosecutes against her ex; the other in which she defends Vincent. But there is a complication. The bride complains that Vincent and Eve spoilt her 20,000 Euro wedding - it’s amazing how much chimpanzees charge. Victoria cannot talk to her. But for being seen to discuss a case with a witness, she is disbarred for six months. During that time, Vincent and Eve get back together.

There is a terrific montage in which Victoria, having fired Sam, throws herself into life with her daughters in their large cluttered apartment. One of them rubs her back and says, ‘I love you, Mummy’. They put whipped cream on paper plates as if having made cakes. Victoria’s face throughout is a portrait of apathy.

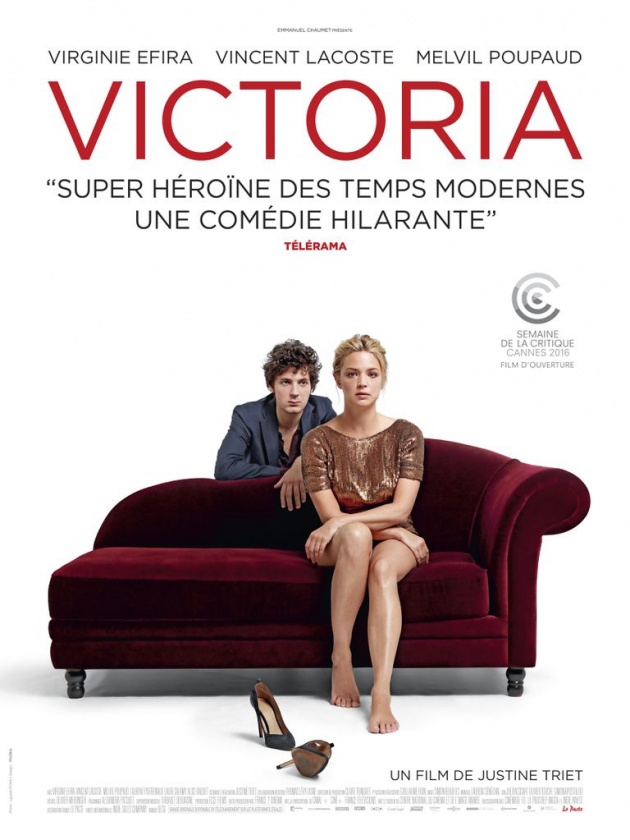

Poster courtesy of Ecce Films

Say that again

Victoria defies categorisation in the conventional way we talk about female-driven comedies. It is not a romantic comedy because it doesn’t focus on a couple that try to make a relationship work. It is not a satire of excessive behaviour in the manner of Absolutely Fabulous. It is not about a woman who learns to love motherhood, as in Baby Boom. It is not a critique of the way women are taught not to feel as a means of getting ahead – Victoria isn’t particularly ambitious. It is absolutely about the absence of satisfaction. At one point, Victoria tells an acupuncturist – she has moved on to acupuncture – that she throws her passion into her work. The bespectacled acupuncturist leans over her. ‘Say that again,’ he sneers. ‘I get passion from my work.’ The acupuncturist is sceptical. ‘Say that again.’ There isn’t a debate. For his part, the acupuncturist doesn’t argue that personal relationships are the only ones that matter. Each character has staked out their territory but, you sense, each is aware of the fragility of their own conviction.

At the heart of Victoria is a sex scene. It isn’t gratuitous – and it is the only one. It shows the only real connection between two of the characters. Moreover, it is very sexy, not in an elaborately choreographed way, with the popping of a champagne cork a substitute for the moment of ejaculation but because passion is communicated.

Sylvia Plath

Victoria’s flat gets even more cluttered when Sam, now re-employed, fills the wall with photographs from the wedding. Victoria’s office has been trashed by a former client who was upset by his inclusion in the ‘Vicky Spock’ blog. Now given police protection, Victoria becomes more stressed. When Sam leaves her, Victoria empties her medicine cabinet and as we see her lying down there is a picture of Sylvia Plath in the background. Why a lawyer would have a picture of Plath in her apartment is anyone’s guess, but it is there to signify ‘suicidal’.

You don’t get that in John Grisham

The climax is Victoria’s summing up whilst under the influence; each hesitant gesture makes us wonder if she’ll make a point with any coherence. The case has become a laughing stock, not least because a dog trainer was brought in to testify to the significance of a Dalmatian wagging to the right (he approves) or to the left (‘go away’). Then selfies taken by the chimpanzee provide vital evidence. You don’t get that in John Grisham.

Efira makes us root for Victoria even though she is – by all evidence – a terrible mother and reckless with her children’s safety. She hails Sam as a saint, but he keeps telling her that he isn’t. Lacoste is a good foil; you can see why Victoria might be attracted to a younger man. He is unformed, a kindred spirit. Victoria has neither siblings nor parents – no extended family. That said, I never did find out the identity of the older woman who looks after her children.

How to shoot a scene in a big city without anyone noticing?

Most of the scenes in the film are interiors, but at two points, Victoria is seen running towards a station. These scenes are shot through the window of a nearby building, the camera panning to follow Victoria. This is a slightly ingenious way to avoid getting a permit.

The verdict

As female-centred comedies go, Victoria doesn’t have any huge laughs or sustained set pieces. You laugh fairly frequently. It does dispense with the stereotype that cold or unfeeling women are aloof and indifferent. No, they are in a state of anticipation for the Eureka moment when it all finally makes sense.

Reviewed at Cine Lumiere, South Kensington, London Saturday 4 February 2017, 15:40 screening. Stills courtesy of Ecce Films