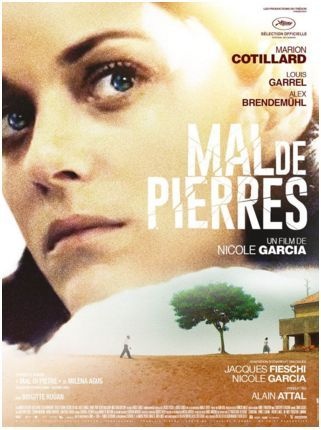

Pictured: Wedding day for Gabrielle (Marion Cotillard) and José (Alex Brendemühl) in Mal de Pierres. Still courtesy of Studio Canal

The title Mal de Pierres refers to stone disease, an abdominal pain caused by the presence of a kidney stone. Kidney stones typically occur when a person is dehydrated, so people living in hot climates are more likely to develop them. You can also develop kidney stones if you have too much calcium and you are consuming way too many oxalates – vegetables like beetroot, asparagus or rhubarb – that prevent your body from absorbing it. Chocolate is also an oxalate. Before seeing Mal de Pierres, I had done zero research into kidney stones or excessive calcium, so at the very least director Nicole Garcia’s film encouraged me to learn about them. Put that on the film poster: ‘An overwrought tale of amour fou’, Wendy Ide, The Guardian; ‘Sent me straight to NHS Direct’, Larry Oliver, Bitlanders.

Re-titled From the Land of the Moon in the UK – you can’t really sell a film called ‘Kidney Stones’ – Mal de Pierres is adapted by Garcia and co-writers Jacques Fieschi and Natalie Carter from a novel, Mal di Pietre by the Sardinian author Milena Agus which was first published in 2006 and was a best seller in France. The film is set in the South of France in the 1950s and focuses on Gabrielle (Marion Cotillard), who suffers painfully from kidney stones and eats standing up. She has developed a painful crush of a literature professor who loans her a copy of ‘Wuthering Heights’. ‘Why don’t you do a correspondence course?’ he asks. ‘I learn better by being talked to,’ Gabrielle replies. At an open air, early evening village banquet, Gabrielle hands him a note. ‘Who wrote this?’ he asks, shocked by the directness of the language. At this point, you might expect Gabrielle to list her literary influences – DH Lawrence, Anaïs Nin. ‘Me,’ she replies. The married professor is disgusted and stomps off. Returning to the table, he gets a nasty shove from Gabrielle. ‘You’re a nothing,’ she cries before running off. Cotillard does a lot of running in this movie in flat shoes and if Tom Cruise is looking for a running partner, he couldn’t do much better.

Visual style

Still courtesy of Studio Canal

The lighting and composition in the first quarter of the film are sumptuous. Early on, there is a shot of Gabrielle walking on a flat mown path in one direction on one half of the screen, whilst farm workers wade through purple lavender fields on the other. In another scene, Gabrielle’s mother, framed by a barn door, calls to her, then when she receives no reply disappears. The camera moves towards the empty door and Gabrielle, stepping out of the shadow, is suddenly illuminated. Given that Gabrielle suffered from kidney stones in her younger days, it is worth noting that in the opening, set in the 1960s, she is eating black cherries without any difficulty. The cherries in her bag are the first things we see as she is driven towards Lyon.

Gabrielle is forced to marry a Spanish farm worker, José (Alex Brendemühl) who marvels at her when she plays the piano, one of the few things we see her doing. Her mother (Brigitte Roüan) brokers the deal. She knows José has a profession – he’s a bricklayer. She can help him start his business. For his part, José fled to France after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. He has seen horrors but keeps them to himself.

The long take

The ‘getting to meet your husband-to-be’ scene shows Garcia’s flair as a director. It is filmed in a long single take with the camera framing the characters in the dining room-lounge in a medium-long shot. Gabrielle enters the room as José is being quizzed. She pours herself a cup of coffee and sits down. Then her sister, Jeannine (Victoire Du Bois) gets up to help herself to cake. At this point, Gabrielle realises that José is there for him and explodes. The use of movement rather than expository dialogue to illustrate Gabrielle’s changing perception is succinct and powerful. Moreover, Garcia remains true to José who says very little and internalises a lot. I can’t think of many directors who would stage this scene in a single take without intercutting a series of looks.

‘I don’t love you,’ Gabrielle tells José, resigned to her fate. ‘I don’t love you either,’ José replies, not to be outdone. ‘I won’t sleep with you,’ she tells him. ‘What will you do?’ ‘There are women,’ he replies, non-specific. At various points, Gabrielle fields herself staring at a crucifix, an image of Christ’s suffering. She suffers too with cramps. At one point, she stands in the river and lifts up her dress to be cooled by running water. This doesn’t entirely work. Cotillard’s performance, by the way, is fearless.

Marriage

They marry. In the church, Gabrielle looks behind her. Perhaps, she hopes her literary professor will interrupt proceedings – or something. There is no joy when the congregation departs, but Gabrielle takes José’s arm – not his hand – almost in spite of herself. She is not ungrateful to be married and José is building a house for her. The marriage is not consummated. They bid each other ‘good night’ without further conversation.

At the end of one evening, José is preparing to go out, to consort with a prostitute. ‘How much does it cost?’ asks Gabrielle? ‘200 francs,’ answers José. Gabrielle disappears to apply lipstick and wear her suspenders in a revealing way. She presents herself to José as a prostitute. ‘Give me 200 francs,’ she says. José does so. Finally, finally he has sex with his wife. But then tragedy – Gabrielle loses her child at an early stage of pregnancy. José, as it turns out, wants a child. Gabrielle is sent to a spa to take the waters – good for kidney stones, see – but as at home does not consort with the other guests. She makes friends with a nurse, Agostine (Aloïse Sauvage) who in turn introduces her to Lieutenant André Sauvage (Louis Garrel) who has been wounded in Indochina. The first Indochina War took place between 1946 and 1954 and ended with a Vietnamese victory in Dien Bien Phu; the reference to the war is the only indication that the film takes place in the 1950s. André, attended by a loyal Vietnamese valet re-named Blaise (Jihwan Kim) desperately wants to return to the front. He worries about the lack of noise from the room next door and asks Gabrielle to investigate. She enters the room and sees the mattress airing out of the window, the bed frame bare. ‘I thought so,’ says André. ‘They take them to Lyon to croak.’ Gabrielle and André become friends. He offers to lend her the book, ‘On Happiness’ (‘Propos sue le bonheur’) by Emile Chartier (aka Alain), first published in 1925. Gabrielle refuses. ‘When I borrow books, things don’t turn out too well.’ ‘Then I’ll give it to you.’ On the inside cover, the book has André’s address, 26 Rue Commines, Lyon.

At the opening of the film as Gabrielle, her husband and son head towards a piano recital, Gabrielle is driven through Lyon, is caught behind a parked truck and sees the sign ‘Rue Commines’. ‘I’ll meet you at the recital, she tells her husband. ‘Go.’

Pictured: Gabrielle (Marion Cotillard) in Mal de Pierres. Still courtesy of Studio Canal

To say what happens next is to spoil the dramatic developments, but we do see Gabrielle run again in a scene staged twice. The first time, she appears to only have one shoe, the second time, she is wearing both shoes. I don’t know if this is a deliberate mistake. At any rate, Gabrielle’s passion is inflamed. She aches for André. Her body is on fire, a sentence she writes many times.

The film offers a positive portrayal of female sexuality. We entirely sympathise with Gabrielle, who believes, rather unscientifically that if desire is satisfied her pain will disappear. Although there are no point of view shots, the story is told through Gabrielle’s eyes. As we discover, she is an unreliable narrator.

The film also compares women’s bodily suffering with the effect of war on men. We sense that José sees Gabrielle not as an object of desire but as a kindred spirit, a person unable to communicate adequately the suffering they experience. In its own way, the film reframes women’s heroism. If men become heroes on the battlefield, then women who struggle with medical conditions are equally heroic. Some viewers of the film might find this comparison absurd, but the struggles of both are selfless (potentially a better title than ‘kidney stones’).

The finale of the film is hopeful, with two characters looking at a village from a distance. One of them asks, ‘which one is your home?’ Mal de Pierres, which competed in the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, was a modest success in France on release in October 2016, opening with 283,843 admissions, source: Allociné: http://www.allocine.fr/boxoffice/france/sem-2016-10-19/ .

Is it, as one reviewer put it, ‘an overwrought tale’? I don’t think so. Just because Gabrielle’s behaviour is driven by her medical condition, it does not invalidate the storytelling turning it into melodrama. Some viewers might find the twist hard to take, but I felt it was earned. Sometimes desire can play tricks on memory. Consummation is not always how we remember it.

Reviewed at Ciné Lumiere, South Kensington, London, Saturday 10 June 2017, 21:00 screening