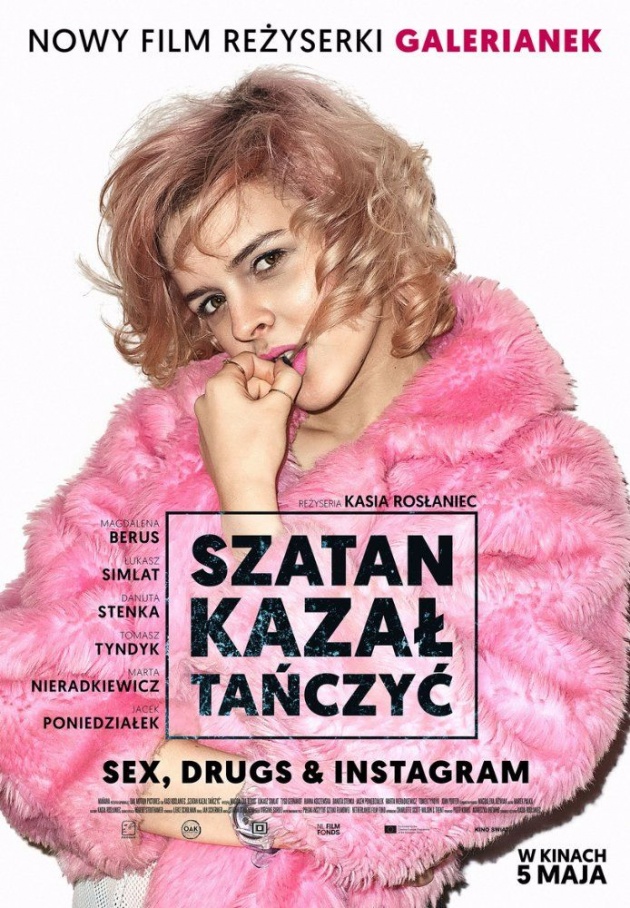

Image: Karolina (Magdalena Berus) walks the streets of Berlin, not hailing the call' Satan Said Dance' in Kasia Roslaniac's film of the same name. Still courtesy of APManana

People in stoned houses shouldn’t throw glass. That’s not right. The heroine or rather the antagonist of writer-director Kasia Roslaniec’s film, Satan Said Dance (Szatan kazal tanczyc), Karolina (Magdalena Berus) is certainly stoned, or coked, or inebriated, or sensation-seeking, or unhappy. She is the twenty-six year old author of a cult novel, ‘Doll’, which is sexually frank and mistaken for autobiography. This is an easy assumption to make. Karolina’s protagonist has a sister. Karolina has a sister. Karolina’s protagonist does drugs. Karolina does drugs. As she talks about writing her follow-up novel – spoiler alert, no writing takes place during the course of this movie, but there is plenty of sex, drugs, dancing, mother-daughter conversations, and scenes in Poland and Berlin – Karolina conducts her on-jerkoff relationship with balding never-should have-worn-a-baseball-cap himbo Marcin (Lukasz Simlat), talks her sister, Matylda (Hanna Kosczewska) into moving in with her in Berlin, rows with and then brings croissants to her mother (Danuta Stenka) and poses for and attempts to seduce British fashion photographer, Neil (John Porter), the British equivalent of Mario Testino, which I suppose is Mark Balls.

Before I describe the film any further, I want to get one thing out of the way: aspect ratio. Roslaniac frames the film for Twitter or Instagram, cutting off the edges. Now some people like their toast with the crust and some without – I am very much on the crusty side. So the cropping of the screen isn’t wholly to my taste. It does however underline the film’s central thesis, that narcissism is narrow. Not only that, but there is a lot of wasted bread out there that could be feeding birds.

It opens with a caption: you can tell a story 42 million ways and it still turns out the same. To a certain extent this is true. A person’s story is written on their face, their clothes, or lack thereof, their expression, their beauty, their pink hair dye and their personal hygiene routine. Mostly, the story is in their eyes. Does it matter when they went to Berlin, whether they had sex with an English speaking African born drug dealer? Does it matter that they don’t answer questions on a Taiwanese chat show that looks vaguely similar to the one endured by Bill Murray’s character in Lost in Translation? Do we care whether they respond to their mother complaining that they look thin by turning on them (‘you look thin; it’s ridiculous – you are not seventeen’)?

This is a Polish film with support from the Netherlands (no pun intended). There is a lot of nudity. Or rather Karolina is shown naked with metronomic frequency. We see her pose for a picture and be asked to hold a stuffed toy. She feels uncomfortable. Then the male photographer steps into frame. He has a flap covering his privet hedge which floats up and down as he leaps in the air and lands. He asks Karolina to photograph him while he is leaping (isn’t that the name of a Sandra Bullock movie?) One, two three. Karolina’s rhythm is off. She doesn’t always want to have sex either.

We see Marcin and Karolina hurry to the bedroom. They strip. Marcin removes Karolina’s undergarment in a faltering ‘why hasn’t it come off your leg yet’ kind of way. Then Karolina doesn’t want to have sex. ‘Let’s have a shower.’ The naked priapic Marcin follows her inside wanting to consummate his desire. ‘It’s too cold,’ Karolina complains. Marcin turns the hot water tap. Then Karolina wants out.

For the majority of the film, the camera is static, except in walking scenes, for example when Karolina fends off the advances of Mango, an African man who speaks to her in English, inviting her to party with his friends. The static camera doesn’t impose, doesn’t judge – unlike some of Karolina’s acquaintances. Her (male) publisher isn’t impressed by her, noting at a party that she doesn’t look good. Later, Karolina gives him a present, a spinning top which she describes as a testament to Polish creativity and ingenuity. The publisher leaves it spinning in his office, making a disdainful remark, passing Karolina off to an editor who gives her a deadline of the 20th of next month.

Shades of JLG

Roslaniac consciously evokes the French New Wave. The title sequence suggests a film by Jean-Luc Godard from the 1960s – you might call this ‘Two or Three Things I Don’t Want to Know About Her’. At one point, two women are lying next to each other on the floor (filmed from above) and there is a flash insert shot of one of the women’s faces as she speaks. Then Roslaniac quickly cuts back to the two shot. In a restaurant scene in which Karolina has a row with Marcin, instead of framing them sitting opposite one another, Roslaniac moves the camera to the right, to frame Karolina on her own with dead space behind her and then cuts to Marcin framed to the left on his own with dead space behind him. Roslaniac wants to show us that in a very real sense, Karolina and Marcin are not together. The scene ends with a long shot of Karolina at the table on her own. There is a member of the waiting staff standing in the background.

Karolina may ingest cocaine and alcohol but she identifies with Jesus Christ. During one photoshoot, the male model poses as Christ. At a market, Karolina points out a statue of a Black Christ; her sister remarks that it is Christ painted black. Poor Matylda also has to carry the paintings and statues with which Karolina wants to decorate their Berlin flat; only finding a flat in Berlin is hard. ‘Why did you make me give up mine?’ she asks.

The opening shows no hint of the nudity-fest and sex-fest – the grump and hump – that is to follow. It begins with two girls dancing in their front room to a Polish pop song. Then an older woman joins in. One of the young women sings at – rather than to – the older one. Then Roslaniac cuts to Karolina complaining on her phone about her assistant, who always wants to do things for her. ‘I told her I like ice cream and all he wants to do is buy me ice cream,’ she complains – the very definition of a First World problem. ‘I should make her get me Asian cocaine’ (the very definition of a Third World problem). At one point, Karolina complains that she doesn’t want to have sex because she has already had sex with a man that day – the other guy surprisingly isn’t jealous. At another point, Karolina allows her bathwater to run over. She floods the bathroom, then part of the flat. Then she opens and closes the front door to let the water out. Unsurprisingly, when the doorbell rings, Karolina doesn’t answer.

Because Karolina identifies herself as almost 27, we think of the ’27 Club’, the list of ‘popular musicians, artists or actors who died aged 27, frequently as a result of alcohol or drug abuse’ (definition courtesy of Wikipedia). Karolina is definitely heading in the wrong direction, but it is never clear exactly why? Is it the weight of expectation for her follow-up? Is it that her lover wants her to bear his children? At one point, Karolina walks around with a balloon stuffed up her tee shirt, even appearing to smoke outside a hospital whilst pregnant, though significantly, the group of hospital smokers – you see them outside every health practice – don’t invite her to join them. She goes to the restroom and removes the red balloon, bursting it – that’s one way of saying she popped her cherry.

There is no ‘conclusion’. The film just ends with another scene of a woman dancing at a club – it is a contrast of sorts with the opening. The scene that gives the film its title is striking. Karolina is on a U-Bahn holding a broken bottle as if to attempt suicide (at some point) or to ward off potential attackers. A young man opposite her appears to mimic her uncertain movements. Then he shows the back of his jacket, showing the words ‘Satan Said Dance’ – as if it were the name of a favourite band like The Slits or Nine Inch Nails. (I don’t think fans of Abba would monograph their clothing in that way.) It is as if the young man were issuing a command to Karolina (that she should party) – or else it is a rebuke (‘Satan said dance – but a nice Polish girl should do otherwise’). Like many scenes in the film it is inconclusive.

What should we make of such a fractured, fragmented film? Probably that female lives are best understood shorn of (male) narrative drive – ye olde history or ‘his story’. There is no inevitability about a woman’s life, no manifest destiny. Just an attempt to make sense of the world through consumption. You’d be hard pressed to be emotionally moved by Satan Said Dance. The story isn’t shaped like a pre-conditioned tragedy or romance. You may however relate to it, understanding that life is not a continuous flow rather a series of fragments. Chance doesn’t play a part in it.

Reviewed at Edinburgh International Film Festival (Odeon Screen 4), Thursday 22 June 2017, 13:15; press screening

Trailer: