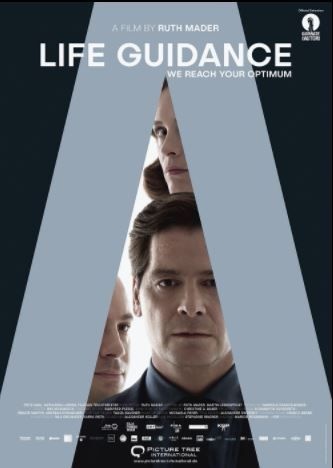

Pictured: Alexander (Fritz Karl) turns his back on conformity in 'Life Guidance', an alternate-reality drama by Austrian co-writer-director Ruth Mader. Still courtesy of Picture Tree International

Life Guidance is a foray into near-future territory from Austrian co-writer-director Ruth Mader. In it, citizens and families living in relative comfort are expected to strive to be optimal. Performance rather than moral well-being is what counts. Perhaps it is better described as being set in a parallel society, significantly one without computers or social media or even advertising. It depicts a way of living that might have been culled from George Orwell’s novel 1984, or dreamed up by Franz Kafka, though one where is there is little talk of the outside world, religion or cultural difference. It is as if Mader imagined a world in which Nazism or white supremacy had won and is no longer a talking point or rallying cry. In so far as there is a sense of the world outside, it is in commodities, whether investments should be embraced or discouraged. In this alternative world, there is no police. If citizens or families diverge from accepted performance or attitudinal levels, a private agency known as ‘Life Guidance’ comes knocking at the door. The service is staffed by middle-aged men in beige overcoats – regular urban professionals wear dark blue – who ring the doorbell and present themselves as a service with whom citizens must engage. The men smile and present themselves as formerly damaged people who have seen the light. They have ways of encouraging conformity, with gifts of robotic rabbits that announce they can see your achievements and films that reflect your deepest fears that amazingly appear to feature you and your family doing things that you wouldn’t believe.

Mader’s hero is Alexander Dworsky (Fritz Karl), a divergent thinker who lives with his wife (Katharina Lorenz) and son in a house that is like a mountain chalet in an urban setting (Austria probably has more trees than people). When colleagues think his company should invest in rice, he argues (successfully) against. ‘Good call,’ he is later told. But Alexander isn’t happy. His father is on his deathbed, cared for in a hospice. When he lies next to his wife and says ‘Ich liebe dich’ (‘I love you’) there is almost a pregnant pause, as if passion had been replaced by an imitation of life, to quote the title of a Douglas Sirk movie.

We've all been there

Alexander’s indolence – he plays football with his young son (the latter is in goal) joylessly and aggressively – attracts the attention of Life Guidance in the form of an agent (Florian Teichtmeister) who looks a lot like the British writer and comedian David Walliams. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t like a ‘Britain’s Got Talent’ judge turning up at my door saying I need help. I’m perfectly happy doing occasional stand-up comedy in New York City, danke schön. A shout out to all at Performance Anxiety at the Broadway Comedy Club, 318 W 53rd Street; I’m not sure if you’re still going. Alexander has no interest in this privately employed bureaucrat telling him, not in so many words, how to live his life, even if the sub-optimal are sent to the Fortresses of Sleep, which sounds like a chain that Superman would visit to buy a mattress. In fact he visits one such Fortress, in which the heavily sedated and – possibly – mentally ill wander around. One man gives Alexander a leaflet advertising his church.

Mader’s film is a commentary on materialism replacing spirituality as the primary goal of life. Of course we can be optimal, but we should also be humble; share the world, don’t own it. There is no organised ‘hippy’ opposition to the urban elite, whose satellite navigation – Mader’s one concession to technology – tells them when they are heading for the unsafe zone. They’ve been chemically suppressed, as oddly sapped of will as Alexander’s conformist colleagues.

Noodles

As in many films that depict an alternate society, Life Guidance reaches a fork in the road. Mader could justify the New World Order by showing what its architects are seeking to protect. Or she could go down a film noir route, showing a man desperate to escape reality. Mader goes for the latter, partly one suspects, because it is a plot choice within budget. You might want to see thousands of Austrians fighting back against an oppressive regime, but it adds an extra zero. The second half of the film has a dream like quality as Alexander masquerades as a Life Guidance employee to break into the building and finds himself befriending two women, one who lost her company, the other, Eva, he meets in a noodle bar in which the customers slurp hesitantly. (I salute Mader’s choice of food used for dramatic effect.)

Mader doesn’t develop Alexander’s wife or even give her a back story. Her brief sub plot involves an accountant colleague who made a mistake and faces being sent to the Fortresses of Sleep. Even he doesn’t become part of the resistance. Rather he is fearful and pathetic.

At one point, Alexander finds himself in a hunter’s cross hairs. He is interrupting a shoot, attended by the Board of Life Guidance who invite him to lunch. They are a happy, cigar chomping lot who have given some people what they want and have done so unapologetically. ‘You help keep the system going,’ Alexander is told. His struggle against Life Guidance leads to a moral descent. Admittedly, we’ve all been there when faced with a smug face, but Alexander’s reaction is more extreme than most. Mader’s final point is to discuss the connection between a moral descent and conformity, as if for many life is a prison.

Pictured: Dinner time for the elite as depicted in 'Life Guidance', a drama set in alternate reality co-written and directed by Ruth Mader. Still courtesy of Picture Tree International

There is plenty to disagree with in Mader’s world view. Kudos to her for attempting a genre that is for the most part driven by technology. But for the satellite navigation, Life Guidance could have been set in the 1930s. It even posits dinner with friends as a private experience, in which a quartet of diners are fed by a server without the need for a knife and fork, rather as if in Roman times. The point that she makes has credence and the film noir plot bubbles along nicely. One of the most human moments is when drugged-up noodle eating bank employee Eva leaves Alexander a croissant for breakfast in a little dish. It is the film’s one single moment of tender, loving care.

Reviewed at the Austrian Cultural Centre, 28 Rutland Gate, London, Thursday 22 February 2018