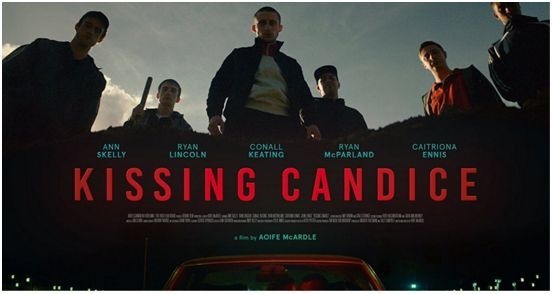

Pictured: Candice (Ann Skelly) and Jacob (Ryan Lincoln) contemplate mouth-to-mouth resuscitation in 'Kissing Candice', a film from Northern Ireland written and directed by Aoife McArdle. Still courtesy of Venom/Irish Film Board

How far from naturalism should you go to tell a story? Fairy tales aren’t particularly naturalistic, except for ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, but they capture our imagination with talking wolves, pigs with poor house building skills and wicked witches offering poisonous apples. Science fantasy isn’t naturalistic either but it shows us how we would like to be, perfectly sculpted into our figure hugging latex suits that aren’t very handy for bathroom breaks taking on villains with excessively cumbersome headgear. Then there are rom-coms, spy thrillers and horror films, not to mention films set in Olde England where the characters sing ‘We Will Rock You’. Let’s not forget musicals.

Just face it, the cinema that we love isn’t naturalistic, but in one area it tries to be, the drama. Narrowing it down a bit, British films have peddled a form of naturalism known as ‘kitchen sink’ since the 1960s inspired by Italian neo-realism and the French New Wave. These films are shot on location and foreground social issues: unwanted pregnancies, homosexuality and racial tensions, to name a few. We watch naturalistic films partly to understand these issues, to give them a human face. Sometimes we are so moved by these stories that we want to change the world.

Because of its power to persuade, naturalism as a mode of representation has been under attack. Its detractors say that naturalist films are nothing of the sort, reducing issues to binary opposites, justice verses injustice. The naturalist painters didn’t attract this criticism, only the naturalist storytellers in literature, theatre, film and television. The naturalists struck back with the sort of action you wouldn’t want to watch – the stoning of a baby on stage in Edward Bond’s 1965 play, ‘Saved’. Naturalistic films suddenly portrayed shocking violence, offering viewers a vicarious thrill akin to a fairground ride – I survived it, will you?

Naturalism was also attacked on other grounds, fabricating the notion that we could know another person by watching their behaviour – the mantra in screenwriting manuals runs ‘character is action’. As psychologists better understood the human brain, we accepted that the choices that people made weren’t governed by morality or free will, but were affected by neurological disorders and curiosities. Even when told it will hurt them, people put their hands in a flame to understand what it feels like. This is one of the reasons why societies organised themselves around representative democracy, where others in groups make choices for us. The alternative is that we would all stick our hands in the flame, otherwise known as Boaty McBoatface or Brexit.

Just as we want stories to make sense of the world, so we refine the way we portray it. We turn to our dreams as a codified way of understanding our wants and needs, the things that drive us and the fears we experience. Omagh-born, Belfast-resident writer-director Aoife McArdle depicts such a dream landscape in her debut feature film, Kissing Candice, moving in its opening moments from dream to reality.

We are introduced to a young couple sitting in a car. Candice (Ann Skelly) kisses mixed-race kid Jacob (Ryan Lincoln), then moves away. He is unresponsive. Then she moves back and kisses him again. Jacob gets out of the car. He walks through the streets bare-chested. His arm is on fire. He walks into a club. Candice sees him, gestures to him to dance and then –

Candice is shaking on the floor. She is having an epileptic fit.

As she describes it later to her best friend, Martha (Caitriona Ennis), Candice dreamt about Jacob. Later she sees him for real.

Ostensibly Kissing Candice is a coming of age story about a girl, a policeman’s daughter, who falls for a boy who is a member of a violent, hedonistic gang. Candice becomes the focus of the gang’s hatred. There is a chase.

That’s the simplified version. The film is more about the inability to assuage male violence.

There is a subplot – more like an undertow – about a young boy who died. Candice’s father (John Lynch) has been assigned to the case.

Pictured: Dancing with the lights on. Jacob (Ryan Lincoln) and Candice (Ann Skelly) in 'Kissing Candice', a film from Northern Ireland written and directed by Aoife McArdle. Still courtesy of Venom/Irish Film Board.

The word ‘plot’ doesn’t really apply to Kissing Candice. There are dramatic events. There is some cause and effect, notably when some young boys recover a gun, then hide it in a post box, upsetting the gang. Essentially the film is about not confronting violence but trying to find one’s own space in a violent world.

Candice’s father has a good relationship with his daughter, or so he thought. On a fishing trip, after he kills one of his catch, Candice throws a thrashing fish back into the water. ‘I thought you enjoyed fishing,’ says her Da. Candice’s epilepsy offers her a way out of the world. In one striking sequence, she is walking down a road and then snatched by the young gang. She then has a fit. Jacob protects her. From that moment on, she bonds with him. Not in so many words – and there aren’t many words in the movie, relatively speaking. But she’s interested. There is one thing that divides them – Candice’s father put Jacob’s brother in prison. But it’s not a deal breaker. The sins of the father aren’t passed down to the daughter, and all that.

The gang becomes suspicious of Jacob after he doesn’t participate in the killing of a suspected paedophile. Believe me, there is very little police protection in this community. Jacob’s house is burnt down. Candice’s father also threatens Jacob to stay away from his daughter, so the poor lad gets it at both ends.

We see the young boy, Caleb, in a flashback – Candice also sees him, peeping through the slit in the pillar-box. He was treated like a mascot. But then he took in a bad drug and overdosed, or something.

The violent gang doesn’t suffer any remorse over Caleb’s death – not collectively. They menace a woman in a laundrette, threatening to put a cat in one of the machines. Then the woman recognises Caleb’s lighter. The twelve year old lad wasn’t old enough to smoke – and yet. One of the boys vehemently denies that it is Caleb’s lighter, as if to say they had nothing to do with his death. His aggressive denial is an admission of guilt, of a sort.

Why is the gang unimpeded in lawlessness and able to phone Candice’s father, warning him that his daughter is in danger? They are, I believe, representative of an inchoate force of hatred in modern Northern Ireland, the mad dog nephews of IRA fighters who have all of the anger and none of the cause, with a boundless capacity for crime and damage. McArdle depicts their energy and restlessness, their unchecked feral instincts. They don’t have homes to go to, at least in the world of the film. They pursue Jacob and Candice to an abandoned church and beyond.

Politics tells us that if we make appropriate interventions, we can solve social issues. In McArdle’s film, no such intervention is possible. At one point, Candice shoots a man up the bum crack with an air pellet just because she can. If there is a form of justice, it is accidental. The meek don’t exactly inherit the Earth, but they can survive a car crash. In Kissing Candice, an anti-realistic, fractured dream of a movie, this counts as hope.

Reviewed at CinemaxX Screen1, Voxstrasse 10785, Berlin, Saturday 24 February 2018, 13:30 screening