Pictured: The publicity image for 'Orione', a sixty-five minute meditative documentary from Argentine visual artist Toia Bonino. Courtesy of INCAA

What is the difference between a film director and a ‘visual artist’? Answer: the expectation of financial success. Orione, the first film from Argentine ‘visual artist’ Toia Bonino is a documentary in seven chapters about the gulf between a mother, Ana Robles, seen throughout the film preparing a cake and her deceased criminal son, Alejandro ‘Ale’ Robles, who was shot in the head by a police sniper after escaping from the scene of a crime. Barely the length of a feature film, running at 65 minutes, but an award winner at the Buenos Aires (Independent) Film Festival, BAFICI (‘Best Argentine Director’) in 2017, Orione is not a conventionally rewarding watch. It does not incite us to be outraged by the poor life outcomes of young men growing up in a housing project in Don Orione, 30 miles from Buenos Aires. Nor is it a film with talking heads. Its emotions are withheld. However, it does have some striking moments. One of these is a police car chase seen from the point of a view of a car behind a police car chasing the suspect. The bumps in the road send our view of the pursuit up in the air. Then there is a moment in a mortuary. We are shown part of a dead tattooed gang member – his chest, wrist and limp genitalia – as he is discussed. There are scenes that are literally in our face as an old man with very few teeth talks about the police. Actually we pay very little attention to what he says. His mouth has teeth in twos and threes. It tells a story without the need for words.

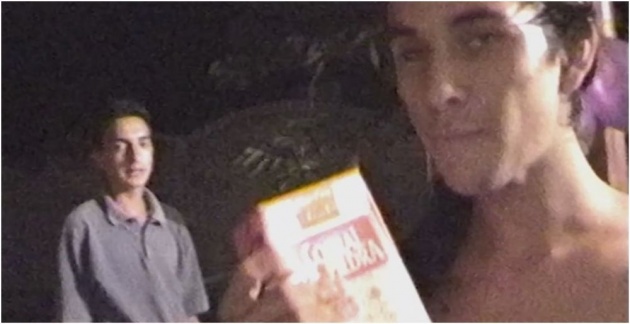

We are introduced to Ale through old video tape. He is seen in a family group. He doesn’t command our attention. We don’t get a sense of who he is. He could be any young man bragging about this or that. Watching these old home videos – and there’s a later one when he climbs a mast – we are not given an easy way to engage with him. There is one moment when he is filmed holding a diploma when we get the slight sense of a life lost. But he robbed people – and, if the testimony is anything to go by, he liked doing it.

The introduction of Ale’s mother telling a story of how she discovered he was arrested is not conventional either. Bonino’s camera focuses not on Ana’s face but on the breaking of eggs into two bowls. Then there is a close-up of an egg yolk before the eggs are beaten. The image is metaphorical. The casual brutality of turning an egg yolk into thick yellow liquid suggests the transformation of a boy (yolk) into something no longer distinguishable from its origin. He has become without definition, a blur, rather like the disintegrating family video footage.

Ana’s story is broadly as follows. She normally made sure her son got to school. However, she was suffering from back pain. Ale promised he would go. He was insistent. He left the house, but didn’t return. Ana got worried. She contacted his friends. ‘He was supposed to be out playing football at 7:00pm.’ Then the next time she saw him, he was in handcuffs. She had never seen him like that before. ‘Hello, Mama,’ he said.

Pictured: The elusive Alejandro Robles as seen in home video footage in 'Orione' a documentary by Toia Bonino. Image courtesy of INCAA

Another striking sequence has a young boy, perhaps eight or nine, being interviewed. We see him in a room, from the side, his face also visible in a video monitor at the top of a wall. He describes how he was in a van with his family when they were attacked by a gang. The boy’s father was taken away whilst the family group was held under guard. They were told not to worry, but did so. We don’t immediately connect this crime to Ale, but it is the flip side to his activity – innocent people under threat.

A further story is told about a couple whose house is singled out for an attack. They fight back. Then there is a further story (told by the perpetrator) about a judge being robbed. His assailants tell him to get another judge off their backs.

We are given the impression of a high crime neighbourhood. But when Bonino goes verité (fly on the wall) they aren’t talking about it. Bonino films a group of young boys talking about girls. Two of them like the same girl. ‘We can share,’ one says, giving his buddy a fist bump. The children play football but Bonino’s camera is static. When they leave the frame the camera stays on a vacated space. You can make of it what you will: here today, gone tomorrow.

Then there is Ale’s letter to his mother – his apology. His words are typed across the screen – white letters, black background. He writes (from jail) about being afraid and not being the son his mother would have wanted. But he has a request: to look after the mother of his (unborn) child, whom he is convinced will be a boy. ‘Look after your grandson,’ he pleads.

In video footage, we see the young woman holding a baby. The baby cries. She inserts a dummy into his mouth. ‘Be in a picture,’ she calls to him, acknowledging the camera. As we watch this footage, we wonder, ‘will it be like father, like son?’

Bonino draws to our attention the air conditioning units attached to the outside wall of many of the apartments. They are of different sizes, an indicator of (relative) wealth – the poorest families can’t afford them. Close to the end of the film, Bonino shows us a bare-chested male looking out of the window. Inside his apartment, we see the ceiling fan whirring furiously. Bonino often gives us static images to read and admire, though we don’t necessarily approve of a serial number being grafted from the chassis of a vehicle, Ale’s gang specialising in stolen cars.

We see a funeral, the camera not quite getting close enough to see the burial. It jockeys for position. We are also shown archive news footage describing the aftermath of Ale’s shooting. Two criminals were killed, three police officers injured. Some of the gang got away. The interviewer asks if they were dangerous. ‘Their intent was clear,’ replies the police spokesman.

Most movingly of all, Ana tells the story of how she was denied access to her son in the hours after his death. ‘You are his mother – where were you?’ The question speaks to the guilt of any parent whose child is a criminal and to the unreachable distance between the law abiding mother and the wayward son.

Bonino doesn’t just do close ups of whipped eggs, she shows us a tattoo being applied. One felon is described as having a Donald Duck tattoo. We see the ink splattering from the outline that it is meant to fill and then being wiped off. Tattooing is a messy business. By showing it close up, it doesn’t look like art or, indeed, a badge of honour.

Pictured: A tattoo in progress in 'Orione', a documentary by Toia Bonino. Image courtesy of INCAA

Orione resembles disjointed pieces of a puzzle that we put together. Ale’s story is not framed as a social problem, more a lifestyle choice. His criminal path is a statement of independence. What can his mother do? She can bake a cake and cover it with green icing, then decorate it to resemble a football pitch. Bonino focuses on the cake decorations - static facsimiles of football players, featureless and amorphous. The soundtrack rises to a clamorous roar, not of hordes of supporters rather suggesting a prison population. In an earlier sequence, we are shown a man being taken to a police cell. How could children’s lives come to this? Bonino focuses on a child’s toy, a spinning windmill in the shape of a flower and takes us (through extreme close up) inside that flower – frantic, going too fast too quickly, a metaphor for lives lost.