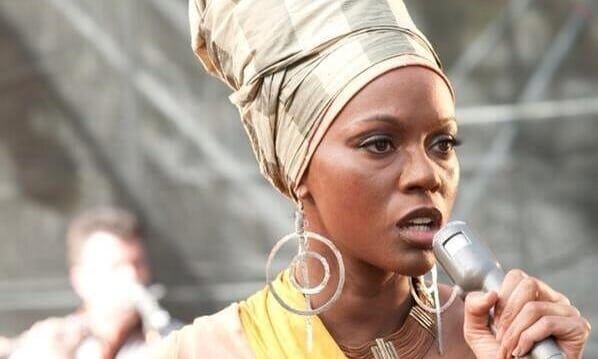

Pictured: Zoe Saldana as Nina Simone in 'Nina'. Still courtesy of RLJ Entertainment

Released in a mire of controversy in a handful of US cinemas in April 2016 by RLJ Entertainment, Nina, a drama about the later years of African-American singer and civil rights activist Nina Simone has finally surfaced in the UK two years later through Sky Movies, a cable TV service. Nominally telling the story of Nina’s battle with alcohol dependency and mood swings in the 1990s, aided by a male nurse, Clifton Henderson, who subsequently became her manager, its writer-director Cynthia Mort was reportedly shut out of the editing room. Cast in her 30s, ostensibly playing a 60 year old woman, Zoe Saldana was not only too young, but her skin colour had to be altered and the bridge of her nose widened by prosthetics. By the way I don’t remember anyone complaining about Robert de Niro’s fake nose in Raging Bull - and as for any actor playing Cyrano de Bergerac, from José Ferrer to Steve Martin to Gerard Depardieu, it is par for the course. Then there is Saldana’s singing – good, but not a patch on Nina.

On a list of films featuring Saldana listed on the website ‘Box Office Mojo’, Nina doesn’t even appear. You won’t find any data on its box office gross either. In short, every effort has been made to forget this film exists. Mort, whose forthcoming film, The Magnificent Room, starring Elisabeth Röhm and Ally Walker, also has a music industry backdrop, has moved on.

The most striking thing about the one and two star reviews of Nina is that they are all written by men, complaining about the film offering a series of clichés. The user reviews on imdb are a little more balanced, showing some love for Saldana – she works hard – and giving the movie a little credit, though Whoopi Goldberg should have been approached to play the role.

Where do I sit? Reviewers need to be reminded to evaluate the film in front of them, not what they want it to be.

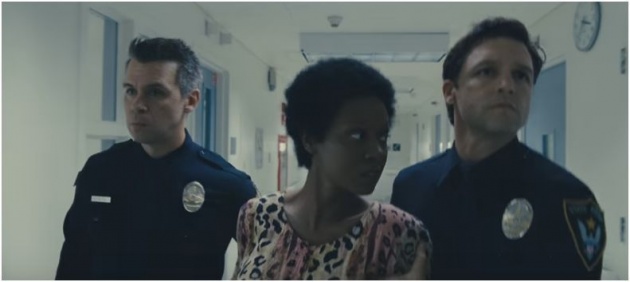

Pictured: Nina Simone (Zoe Saldana) being taken for treatment in 'Nina', a drama written and directed by Cynthia Mort. Still courtesy of RLJ Entertainment

Let’s start with the descriptor ‘biopic’. Nina is not a biographical motion picture. It does not attempt to tell her whole life story. True, in the opening scene set in the late 1940s, we see her playing classical music to a predominantly white audience, with her parents standing at the back. Young Eunice Kathleen Waymon (Vivie Eteme) as she was back then pauses and announces that she won’t start playing until her parents sit at the front. ‘But look at all those people who have come to see you!’ Eunice is insistent. Consternation follows, but hers is a will to be done. Cut to almost 40 years later (1985) and Nina is in a record company office asking her royalties. When told there aren’t any, she pulls out a gun. She is subsequently sectioned. There (according to the film) she meets Clifton (David Oyelowo), who has, as they say, a bedside manner.

The fact checkers will tell you that Clifton was only with Nina from 1995 to 2003, during the last eight years of her life and after she had recorded what turned out to be her last studio album, ‘A Single Woman’ in 1993. So the film tells a few pork pies – well, a whole pig’s worth. It ends with a free concert in Central Park, which at least one journalist says did not take place. It also shows Nina attempting to record, though no record was released under Clifton’s stewardship.

In short, you have to forgive the film a lot. But how do you dramatise a friend-turned-manager who nursed Nina back to performing a full set in front of an audience? Incidentally, I saw her perform in the late 1980s and my one memory was that the concert didn’t have a whole lot of singing in it.

Where Nina really succeeds is in being a film about an artist enraged by her audience, who in France where she lived for many years treated her like background music. I’ve been at functions where a string quartet have played whilst guests consume champagne (now prosecco) and canapés. I often stopped to listen, then applaud, but was definitely in the minority. If it is your gig, if you are the headliner, then you deserve respect. Simone rightly in my view attacks the indifferent crowd. There’s a reason why the audience is shrouded from the performer in darkness.

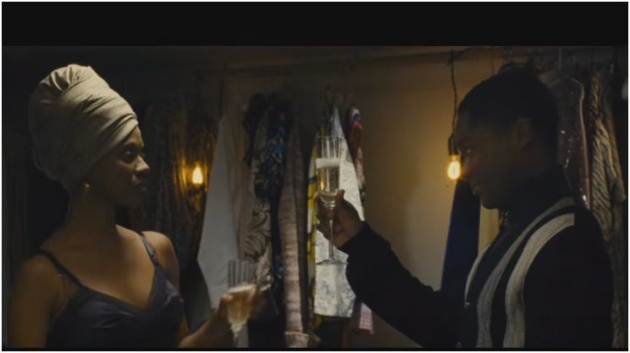

Pictured: A champagne moment. Nina (Zoe Saldana) and Clifton (David Oyelowo) in 'Nina'. Still courtesy of RLJ Entertainment

Bringing back Clifton to her home in France, on a salary of $2,000 a month, Nina is appalled that the man taking care of her rips the covers from the windows shielding her from sunlight, waters down her champagne (big mistake) and attempts to give her food and medication. The food she eventually accepts, but medication is a no-no. She goes to Nice – everyone loves her there – and after being the toast of the party, she makes a pass at Clifton. He refuses. Her response is to ask him to procure a young man for her. Clifton does so, but then returns to Chicago without a job. Nina flies to America to offer him the job as her manager. He returns to France attempting the difficult task of getting her a gig, where her volatile reputation precedes her.

The film is punctuated with extracts from a radio interview in which Nina/Saldana wears a big floppy hat and moves her head slowly. At times Saldana’s performance seems like an impersonation, but at its best it is an approximation. She gets the spirit of Nina’s intransigence if not projecting the depth of her talent. In the film’s best scene, Clifton pays her a compliment. In performance, she is extraordinary. No, counters Nina, I am just a black woman. The scene conveys an artist who sees herself a distillation of discontent, as true in musical performance as in eating a bowl of cereal. You can identify with Nina’s intolerance of B-S at this point.

There are flashbacks: Nina being separated from her child (set to the song ‘Brown Girl’); a performance of ‘Young, Gifted and Black’ to the author, Lorraine Hansbury (Ella Thomas) who inspired the song; the announcement of the death of Martin Luther King – Nina wants to take a gun to the assassin; and, after a phone call to comedian Richard Pryor (Mike Epps) a brief scene of Pryor’s act in the late 1960s. There is a reference to Pryor’s history of domestic violence and a suggestion they might have had something.

The second best scene has Nina opening a fan letter, actually a cassette from the daughter of one of her admirers, containing a recording of the song ‘Four Women’ – the song itself deserves a second listen. I thought it was about the same woman but with different names (Aunt Sarah, Peaches), like the kid in Moonlight. It’s actually about defying other people’s definitions of oneself.

Having given absolution to the filmmaker, you have to consider Nina as failed Academy Awards fodder. It does however have something to say about the audience entering into a compact with a work of art, be it a film or musical performance. Give it attention and see what’s there before rejecting it. Nina ends with the singer forgiving the United States for its treatment of African-Americans – well, at least for one (fictional) night only. We should forgive the initial response to the movie and complaints that Mort had no right to attempt to dramatise young Eunice’s story.