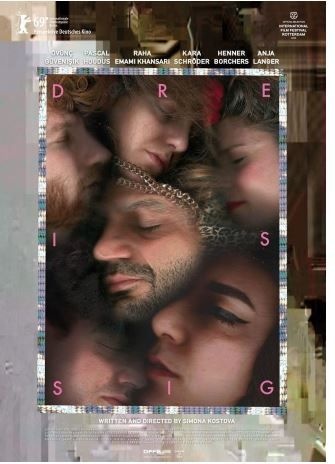

Pictured: The morning after. A group of friends consider breakfast in the 24 hour party pooper Berlin-set drama, 'Dreissig' (Thirty) written and directed by Simona Kostova. Still courtesy of Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB).

Some people set goals over which they have no control: to lose their virginity by the age of twenty-one, to acquire a mortgage by twenty-five, marry by twenty-nine and have children by – what do you mean you’re pregnant? Such deadlines are arbitrary and for the most part meaningless. In my country, we don’t know what is happening on March 30th, thanks to the political class who can neither agree a destination, a route nor even a mode of transport - just how many meaningful votes are actually meaningful?

Personally, I missed most of these deadlines: experiencing affection-based sexual intimacy at age 24, signing the mortgage papers aged 33, marrying aged 29 (yay, met that one) and fathering a child – what do you mean you’re pregnant? For some, thirty is an important birthday: by then, you should be well on your way. For me, I was sixteen years away from a cardiac arrest, fortunately surviving to count my missing teeth. I hadn’t yet written my novel or the great British screenplay. (Is there a great British screenplay? If so, I would probably nominate Four Weddings and a Funeral or God’s Own Country.) But there is still time. As no one in my family has said, where there’s a tax return, there’s hope.

Bulgarian-born but German-based writer-director Simona Kostova has taken this significant age as the title of her highly accomplished, scream from the rooftops it is so good, debut feature film, Dreissig. Ostensibly, it follows twenty four hours in the lives of six Berliners, five friends and a hanger on. Structurally, it is a bit like a ghost story. Each character faces something which makes them scream, cry or leave the room – much like the goals I mentioned above. It ends with them having breakfast together, chattering blandly. We hear the sound of cutlery against plate as food is cut, scooped or scraped. It is a haunting image. It haunts me still.

A word of caution: Dreissig takes its time, but then getting to thirty isn’t a sprint. It begins with the camera focussed on the sleeping face of Ovünç (Ovünç Güvenişik). We don’t immediately see him wake up. His slumber is sound. The camera takes the position of a lover who has got up to fetch a glass of water in the middle of the night and stares down at the man to whom they have pledged their future. Is he the one? Will he ever shave? At least he doesn’t snore or take all the bedclothes in the way that men do only when someone else shares their bed.

The sound of a vibrating mobile phone breaks the monotony. Ovünç wakes up, gets up slowly and searches for the source of his sleep disturbance. We note that he is partially dressed and literally sleeps on pillars of books that support his bed frame. It takes a while for him to find the phone. It rings three times. When he answers it, he discovers it is not an emergency. His best friend Pascal (Pascal Houdus) wants to confirm the arrangements for the evening. He – Pascal – asks if Raha (Raha Emami Khansari) will be there. Ovünç has invited Kara (Kara Schröder) so Raha will also come. Ovünç mentions that he must do some writing. The call ends. Ovünç lights a cigarette and smokes it. He opens the window but closes it in response to the noise outside. He then practices catching another cigarette in his mouth. Once successful – and it takes him several tries – he lights it. Then, knowing he will be entertaining later, he starts vacuuming.

How do you justify scenes that show activity but don’t drive the story forward? First, you establish pace and mood to convey the emptiness of a life. You also make the audience feel they are watching real life in real time and that they are outside the action. Dreissig doesn’t have what screenwriting tutors call a ‘principal viewpoint character’. It does however have a principal viewpoint: the fear of loneliness.

The second scene – also an unbroken single take, with the camera slowly revealing more of the location – is set in Raha’s apartment. It was Raha and Pascal’s apartment but Pascal is moving out. Kostova’s framing tells us a lot: Raha has the window open and is smoking a cigarette. Pascal is inside on the sofa. He talks a lot. Raha says very little. The point at which one person’s conversation would ignite the other has gone. Pascal contemplates the newly Scandinavian nature of his ex-girlfriend’s apartment, bereft of his possessions save for a shelf, which Raha, wearing a ‘Refugees Welcome’ t-shirt, invites him to take. He describes two rats with whom he has become acquainted in his new apartment – not metaphorical ones, actual rodents. He wonders about Raha’s ability to pay the rent – we learn later that she is an actress, though not one that we imagine has firm prospects. Raha explains that Kara (Kara Schröder) will be moving in. ‘But how will that work out?’ Pascal asks, adding ‘Kara writes through the night,’ as if this detail may contribute to a change of mind. This isn’t an issue. Pascal asks if he can get ready for work at the apartment and Raha moves from the window to the hall, looking at herself in the mirror as he changes his clothes. She doesn’t want to look at him. Managing to make a shirt and tie seem scruffy, Pascal walks over to Raha and begs her to take him back. The room could be split in two. She could have half a shelf. Raha reminds Pascal that he dumped her. He considers this. For the final time, perhaps, they hug. We see a curl of Raha’s hair loop under her eye, suggesting a monocle – it’s a beautiful image. Then Pascal leaves.

Pictured: Pascal (Pascal Houdus) dresses whilst Raha (Raha Emami Khansari) can't wait for him to leave in 'Dreissig', a Berlin-set drama written and directed by Simona Kostova. Still courtesy of Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB)

There is a heck of a lot going on below the surface, some of which is hinted at in dialogue. Pascal is clearly animated and keen to be perceived as moving in some direction, or at least moving, just as Ovünç states his intention to write. What they have in common is that they are not going anywhere. Moreover, they haven’t faced up to their inertia.

If you expect this is to be a film about people waking up to their own shortcomings, you’ll be disappointed. There is no ‘learning’ - an American phrase, but we Brits like it too, sort of. In real life, how many people come to a realization that they ought to stop what they’re doing? At any rate, Pascal lives in the moment, as we see in his next scene, when he peddles furiously down a Berlin street. He stops as if having arrived somewhere – his place of work – but then encounters someone from his past, an old school friend, a young man with glasses, who is with a girl. He is in Berlin too – what are the odds? The old school friend does what we all would do – phone his mother. Really, he calls her and hands the phone to Pascal who puts on his most enthusiastic, charming to see you, ‘tschuss, tschuss’ voice. The old friend can barely keep his jealousy of Pascal, ‘a young CEO’, out of his voice: ‘How much do you earn? 4,000, 5,000 per month?’ However, Pascal upends the conversation, extolling the virtues of Google Maps. (Come on!) He describes the whooshing round the world that Google simulates – from Berlin to Tokyo – as something he wants to do. Indeed, he’s going to Tokyo. The friend, by now an acquaintance, no, wait, I never really knew him, suggests they should meet for a drink some time. ‘Why don’t we go for one now?’ counters Pascal. However, his full-on bonhomie only repels the young man – perhaps Pascal’s intention all along. They part and Pascal sits on some stairs.

We are introduced to Kara in Raha’s kitchen. Raha is breaking eggs into a bowl. We later understand that it is for Ovünç’s birthday cake which – spoiler alert – doesn’t get eaten. Kara tells the story of a young female artist, 1 metre 60 tall, who finds herself surrounded by tall men listening to her plans for her next show. As she describes her theme – masculinity and cannibalism – the men disengage. Kara starts to like her. She is saying the right things, making the case – in other words, she is an authentic feminist. Kara is about to reveal something when Raha turns on the blender. Kara stops speaking, but then switches on a fan which blows her long blonde hair. The contrast between fan and blender is inexplicably funny and beautiful at the same time.

Pictured: Raha (Raha Emami Khansari) works the blender whilst Kara (Kara Schröder) hits the fan in 'Dreissig', a Berlin-set drama written and directed by Simona Kostova. Still courtesy of Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB)

At a bar, we meet Henner (Henner Borchers), a tall lightly bearded man. On the arrival of Ovünç he breaks into ‘happy birthday’. After getting the crowd to join in, he shows Ovünç to a table and offers him a partly consumed glass of beer, joined by a young woman, Anja (Anja Langer) – the ‘hanger on’ of the sextet. He then in theatrical style opens his brown coat, out of which he pulls a bottle of spirits. ‘You’re not allowed to do that in here,’ he is told by a member of staff. Ovünç invites Anja to the party later just as Pascal arrives at the bar. ‘We’re going to Henner’s,’ he explains. Pascal is disappointed. He is not in the mood for Henner. As they leave the bar, Henner jumps out as if to surprise Pascal. We understand Pascal’s apprehension completely.

Pictured: 'Match me, Henner'. Henner (Henner Borchers) offers Ovünç (Ovünç Güvenişik) a light, watched by Anja (Anja Langer) in 'Dreissig', a Berlin-set drama written and directed by Simona Kostova. Still courtesy of Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB)

After a brief scene in which Raha and Kara get ready – they contemplate their future double chins – there is a jump cut to darkness and the presentation of the birthday cake. The rest of the film is set during the long night. The arrival of Anja, the orchestration of two taxis to a bar, Twin Pigs, that Ovünç enters then leaves, a dash through road works and the other happening places that the group visits.

There are explosions: Kara, who has fallen for Ovünç, curses Anja and her [hair] bun, then hugs her. Henner faces an old man in a club and breaks down. Ovünç explains that he is not ready for another relationship. Pascal and Raha flare up.

The big finale is at a small gig, as the band Black Bear Basement play the soft jazz tune, ‘Kryptic’. We are as hypnotised as Raha is, watching them. You want to purchase a download afterwards – though people my age still say ‘buy the album’. What can I say - I do still purchase CDs.

When we consider a life change, be it aged thirty or at any age, we review the small moments that we identify retrospectively as way stations. We reflect before moving forward. Kostova’s film invites reflection. It is also exhilarating and honest without trying to round events off neatly.

Although the characters are named after the actors playing them, Kostova did not encourage the cast to play themselves. It was more a point of convenience. The cast was also a mixture of professionals and non-professionals. For example, Kostova had known Güvenişik for years. Whilst portraying the yearning for connection, Kostova doesn’t come to any conclusions why this group doesn’t connect. In a goal-orientated world, are we supposed to have time for friends? Are we preoccupied with the notion that the company we keep says something about us – ‘x’ is an alcoholic, so I must be an alcoholic too? Films at the very least should start discussions rather than present a pre-packaged view of reality. Dreissig does this in abundance.