Pictured: Miriam (Teresa Sánchez) befriends young single mother Evelia (Gabriela Cartol) - seen here with an apple - in the hotel-set observational drama, 'La Camarista' ('The Chambermaid'), a Mexican film co-written and directed by Lila Avilés. Still courtesy of Kino Lorber (US), New Wave Films (UK)

Character, as screenwriting manuals explain, is action. We judge people on screen as well as those we meet in real life through what they do. Do they lie or tell the truth? Are they selfish or selfless? Are they bullies or victims? In movies, unless they are clearly titled Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, we assume the central characters are virtuous, that they have respect for others. This assumption is based on the conventions of narrative cinema: that the protagonist is the audience’s surrogate, a reflection of you or me. We believe we are virtuous, although we’ve also made a few mistakes. Narratives are often redemption stories in which the audience takes a bath – as opposed to a shower, which is far too short.

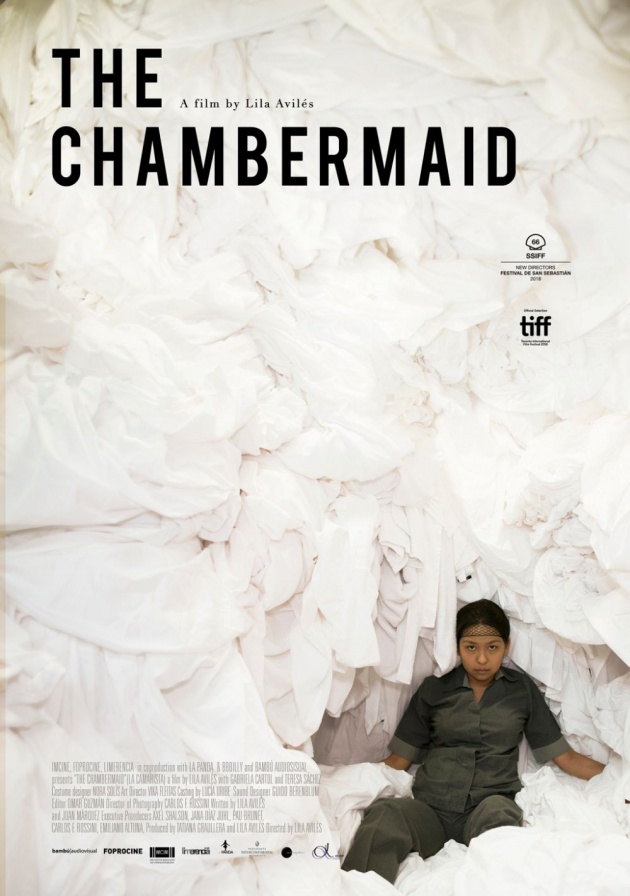

How can we tell if a film’s protagonist is virtuous? This question is raised in actress-turned-director Lila Avilés’ debut feature film, La Camarista (The Chambermaid). The screenplay (guion) is by Avilés and Juan Carlos Marquéz, with contributions from Beatriz Novaro and Alejandra Moffat. Set in Mexico City at the Intercontinental Presidente Hotel, it shows a young, presumably single mother at work cleaning rooms in a luxury hotel with intense speed and attention to detail.

When we first see the hairnet-wearing Evelia (Gabriela Cartol) in her grey service staff outfit – grey is the colour of invisibility - she has her back to a messy room. There is an open suitcase, clothes scarcely unpacked. The white duvet is crumpled. How could someone leave a room like this? Yet it is almost as if Evelia is enjoying a moment alone listening to the sound of a dehumidifier before she springs to action. The humidifier is switched off. Evelia then works speedily, bagging mess and then having to fish something disgusting out of the toilet. We don’t see what it is – Evelia is shown flushing a toilet, then handling a bag full of stuff with her right hand, pinching the bag shut, while using her left to fish in a pocket to pull out another plastic bag which she vigorously shakes open in order to put the filled bag inside it. It is a dexterous motion. Evelia also addresses the matter of the messy bed and then makes an unexpected discovery. I won’t spoil it but the dynamic of the scene is suddenly altered. Even though the moment is exceptional and Evelia is displaced in the scene, it is also just part of her working day; an incident to put to one side.

We discover that Evelia works alone on the 21st floor of a 42 storey hotel. This is an example of classical movie storytelling, being introduced to a character halfway through their journey. One of the reasons we get annoyed by biographical motion pictures and superhero origin movies is that they take too long to get going. Why can’t they just start on the 21st floor? Incidentally superhero movies like Spiderman: Homecoming are ditching the origin bit so they can get into the action quicker. Even Mary: Queen of Scots omitted the title monarch’s brief first marriage – well, they would have needed subtitles, a bit of a turn off for some.

Evelia desperately wants to work on the 42nd floor. Why? As we discover, there are fewer guests and the opportunity for bigger tips, by which I mean the spoils of abandoned property. Early on, Evelia reports a charger that was left behind; the guest has now left. Elizabeth, a colleague, puts it in a drawer. Evelia is interested in a red dress that she also found: has it been claimed? If it is to be given away, ‘We are going to give it to you. You are first in line,’ Elizabeth tells Evelia. Evelia gives her a little smile.

Let’s return to Evelia’s virtue. She is discovered by her supervisor, Nachita (Clementina Guadarrama), staring out of the window. ‘Why are you here?’ Nachita asks. ‘This is a restricted area.’ ‘I thought the building was shaking,’ she explains. Nachita fulfils her role as expository supporting character, telling Evelia that the 42nd floor is now open. ‘Señor Miguel Angel told me. I told him about you.’ This spurs Evelia back to work. We then see her cleaning a room occupied by a Japanese photographer – the books are a giveaway. Evelia straightens them. She is also fascinated by the pictures and by the litter – squashed single use plastic bottles. She pours the contents on the litter bin onto a plastic bag then examines them, putting some of the stuff into her pocket. Her intimacy with the private possessions of the hotel guest set me on edge. I identified with the guest and wouldn’t like to have my possessions inspected. I could understand why she pocketed some of the waste – reuse, recycle and all that. Indeed, she is exercising a very human curiosity about those who have more – or different lives – than she does. Nevertheless, you are forced to think about the people who cater to you as a guest. Are they fairly treated?

Evelia goes for her lunch and selects some popcorn. She then takes it into the elevator and starts chomping it, asking to be taken to the 42nd floor. ‘You’re not supposed to eat that in here,’ the operator, a middle-aged woman, tells her. In an earlier scene, as the lift stopped on the maintenance floor and a chef asks to travel to the laundry floor, we see him eat a snack without reproach - one rule for some, another for others. Evelia stops. We see her by a window eating popcorn, then taking it and putting it into small packets – perhaps the bags taken from the photographer’s room. She puts each filled packet on a shelf. These are almost like small portions saved as snacks – rare treats. She is interrupted by a call on the radio. Señor Morales wants some more amenities. Evelia insists she had given these to him. He’s a VIP guest and wants more.

You expect the next scene to be in Señor Morales’ room but Avilés wrong-foots us, instead showing Evelia switching a light on and filling her amenities tray. Why is this important? Because the entire contents of her tray end up in Señor Morales’ room – he is stockpiling as if there would suddenly be a shortage or else, as we might conclude, he is milking it. We see him sitting on a bed in a white hotel robe, applying an ear bud, while watching an American television channel. Señor Morales barely acknowledges Evelia as she enters, jerking his head towards the bathroom with a grunt. Evelia discovers his considerable stockpile of shampoo bottles, which she augments as instructed. ‘Leave four or six small towels,’ he tells her. Once can scarcely imagine their use, at least not while watching Fox News. He files his nails as she leaves and doesn’t say ‘gracias’. The television show refers to ‘man remains alive as animal’. We know.

Pictured: Evelia (Gabriela Cartol) showers at work, but not fully clothed, in the observational drama, 'La Camarista' ('The Chambermaid'), a Mexican film co-written and directed by Lila Avilés. Still courtesy of Kino Lorber (US), New Wave Films (UK)

The film’s visual style is notable. Avilés has a background in documentary and will cover action from one angle only, either behind Evelia or showing her in profile. Some of the scenes are filmed in a long, extended take to increase the impression of realism. Even when a scene is dead, such as showing two women with their backs to us in an elevator, Avilés will add a detail, such as the elevator operator applying a hairpin. There is also very little music. Avilés prefers diegetic sound, such as a light being switched on or the sounds of activity. It symbolises the emptiness of hotel life, the airless nature of it.

Evelia’s only link to the outside world is a telephone. She calls her babysitter to check on her four year old son. We discover, in a later scene, that she is twenty-four years old. We guess at her back story: a teenage romance that went sour after Evelia discovered she was pregnant. Perhaps she didn’t tell the father. Perhaps something bad happened to him. At any rate, when Evelia is looked at by a man, specifically the window cleaner who daubs a heart shape on the window, Evelia does not want to know.

In as far as there is a plot, it involves Evelia angling for the 42nd floor cleaning assignment. However, she is asked to mind the baby, named Martincho, of a wealthy Argentinian staying at the hotel; her husband, we assume, has business in the city. We first see Romina (Agustina Quínzi) wiping her breasts having fed Martincho and asking Evelia for this favour. Evelia is hesitant. It isn’t her floor. She is busy. She is only there because Skinny, a male cleaner, asked her. Romina talks while she showers, describing how her husband Edu got mad with her after she dropped the baby. ‘Young mothers drop babies,’ she insists. She asks about Evelia’s son and whether he plays with his penis. The social gap between Romina and Evelia is huge. When Romina kisses her on the cheek, it feels like a taboo act, even as she asks, ‘same time tomorrow?’

There are a number of hotel employees on the make. Tita (Marisa Villaruel) who works in uniform collection, notices that Evelia’s hands are very dry and offers her a lotion, giving her a sample. She also tries to sell her Tupperware – plastic containers for food. Then there’s Miriam aka Minitoy (Teresa Sánchez) whom Evelia meets in the adult education class, where a number of employees study to pass a General Education exam. She sells toy glowing saucers for 45 pesos, adding that they are worth 70. She also persuades Evelia to receive an electric shock in exchange for cleaning some of her rooms. Evelia endures the pain and the moment shared with Miriam in the laundry cupboard is almost sexual. However, Miriam is not a virtuous person. When Evelia offers to help her clean a room after Miriam helped her out of a spot, specifically Evelia’s period, which stained a duvet, she is left with a large mess to clean up, though with no other surprises unlike the opening scene. Then when Miriam cleans a room for Evelia, she does not do so to a high standard. Evelia has to clean a toilet supervised by Nachita minutes before the guests are due to occupy the room. It is humiliating.

Evelia’s fear of men is illustrated when the tutor, Raul, offers her a copy of Richard Bach’s novel Jonathan Livingston Seagull. When Raul’s back is turned, she leaves the classroom to douse her face in water. Yet she wants the red dress; there is a contradiction in her character. The dress doesn’t represent an acceptance of her own sexual power – how she can use her attractiveness to get what she wants – so much as her ambition. The pay-off with the dress, filmed at a distance in a laundry room, illustrates this powerfully. Aside from her involuntary period, she does her exercise her sexuality in a scene with the window cleaner in which she appears to play to his fantasy, or, quite possibly is having a nervous breakdown.

Jonathan Livingston Seagull is about a young gull who tries to achieve perfection in flight, at the expense of searching for food, which leads to the gull being ostracised from the flock. It is a celebration of individualism. Evelia is a similar individual, but her focus is on being recognised as a professional. She is caught by surprise when Romina appears to offer the chance to move to Argentina, taking her four year old son Rubin with her, to be a permanent live-in nanny. It is not a firm offer, more a ‘you know what would be great?’ The gap between Romina and Evelia is illustrated when Romina asks for directions to a market. Evelia explains the public transport routes. Romina, who has complained about what the city does to her skin and her throat, would prefer to take a taxi.

Pictured: Offered a copy of 'Jonathan Livingston Seagull', Evelia (Gabriela Cartol) retreats to the bathroom in 'La Camarista' ('The Chambermaid'), a Mexican film co-written and directed by Lila Avilés. Still courtesy of Kino Lorber (US), New Wave Films (UK)

Pictured: Offered a copy of 'Jonathan Livingston Seagull', Evelia (Gabriela Cartol) retreats to the bathroom in 'La Camarista' ('The Chambermaid'), a Mexican film co-written and directed by Lila Avilés. Still courtesy of Kino Lorber (US), New Wave Films (UK)

In a conventional drama, Avilés would build to a confrontation of sorts. Instead, there is something else. At the climax Evelia stands on the roof of the building. The camera reframes her so that she is seen not against the backdrop of the city but of the sky. This we think of as her Jonathan Livingston Seagull moment.

Anyone who has done service delivery jobs will identify with Evelia. Her sins are only that she takes what is discarded and uses the hotel phone for personal calls, in one sequence while a guest is filling an ice bucket. The noise is so loud that Evelia asks, ‘are you all right?’ Her story reminds us that to be successful, it is not enough to work hard - you have to be seen to do so. The final scene is a reminder that there are other points of solace. Evelia has the power to make Tita and her young son happy.