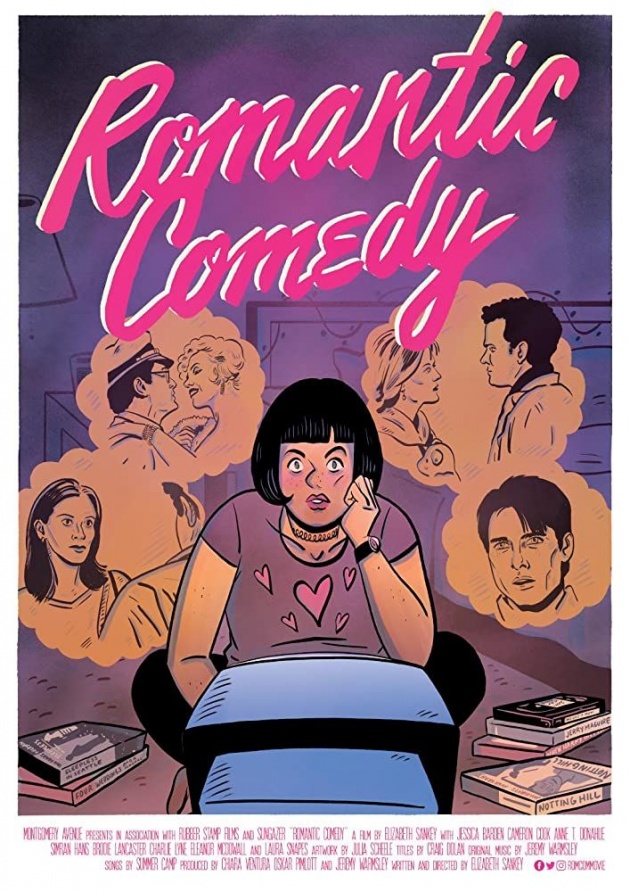

Pictured: The poster for 'Romantic Comedy', a consideration of the popular 'rom-com' genre compiled and directed by Elizabeth Sankey. The film is a Montgomery Avenue Production. Stills from the films referenced not available for reproduction under copyright law.

‘I am standing at the altar about to be married. Little do I know that the love of my life is racing towards the church on horseback. I am an advertising executive and I fall for a charming man. Only he is also in advertising – a rival.’OK. These are not exact quotes. However, they illustrate British musician turned film essayist Elizabeth Sankey’s voiceover at the start of Romantic Comedy, a consideration of the tropes of the one Hollywood genre aimed squarely at women. Her basic point is that, for all the contrivances and bad messages that they contain, ‘rom-coms’ move us because they give us that most human connection, when two people who might otherwise not know each other, kiss. It is weird watching the movie during COVID-19 lockdown, when people are actively discouraged from meeting someone new. Social relationships are frozen in aspic, like ‘Dino DNA’ in Jurassic Park. I wonder if humans will remember how to socially interact after a vaccine for Coronavirus is found. Or will we continue to shout ‘two meters’ at one another.

Romantic Comedy is part-clip reel, part-opinion piece. It is like a podcast with movie clips underneath. You could listen to most of it and not lose the thread. There are no interviewees talking to camera. Instead, various contributors talk over the movie clips themselves, occasionally giving way to allow actual movie dialogue. Sankey, whose band Summer Camp contributes to the movie’s soundtrack, edits out some of the most notable exponents of the romantic comedy genre. The biggest ‘rom-com’ of 1981 was Arthur, starring Dudley Moore and Liza Minnelli as a rich drunk and the woman who saves him. In Sankey’s edit, Father of the Bride about a reluctant dad (Steve Martin) giving away his daughter, is more of a romantic comedy. As for Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, without which When Harry Met Sally would not exist, it has been edited out of movie history altogether owing to accusations accepted as fact about its maker.

The basic component of the genre is that two people – usually attractive, usually male and female and usually but not exclusively white - fall in love on screen. But why are they so middle class, complains Sankey, neatly forgetting about Maid in Manhattan in which a Hispanic American hotel maid (Jennifer Lopez) falls for an American politician (Ralph Fiennes)? Why are they not interracial, she asks, neatly forgetting about Maid in Manhattan, etc? Sankey self-selects to make an argument – sometimes convincingly, sometimes dredging up straight to DVD (in the UK) movies (The Last Kiss, starring Zach Braff and Rachel Bilson, a remake of a Gabriele Muccino movie) to stretch a point.

I think that Sankey should have stuck to popular successes and delineated between teenage romantic comedies – the entire oeuvre of John Hughes (Pretty in Pink, Some Kind of Wonderful and Sixteen Candles) doesn’t get a mention – and adult romantic comedies. Sankey and her mostly British contributors (Jessica Barden, Anne T. Donahue, Cameron Cook, Charlie Lyne, Laura Snapes and others) make some good points about some of the movies they skewer, but they take some short cuts and segues, including to the 2017 British drama, God’s Own Country, that don’t make sense. Personally, I would have had less Josh O’Connor, more Molly Ringwald.

There is also something particularly grating about a group of British middle-class voices complaining that the genre is too middle-class. Hollywood films do not generally suggest that romance is a way to social advancement – that is a British thing. In any case, in what sense is Pretty Woman, the film that made Julia Roberts a star, middle-class?

After an opening that situates Sankey’s love of the genre back to her teenage bedroom – cue a montage of other teenage bedrooms – she introduces us to the origins of the genre. In the 1930s, she notes, cinema was frowned upon as an art form. It became a place where women and immigrants could make movies. The 1930s romantic comedies showed that women could be the equal of men – after all, so the saying goes, Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, but backwards; Sankey does not quote this, but it bears repeating. In the 1940s, women had to support the war effort. By the time of Doris Day movies, women could have successful careers but were shown to give them up for a man. Sankey does make an exception – Marilyn Monroe – whose innocent desirability made men stupid. Sankey does not delve into the narratives of Monroe movies the way in which she does with The Last Kiss, in which Zach Braff’s character cheats on his pregnant wife and sits outside the family home for three days begging forgiveness; commentators wonder how he went to the bathroom. Instead, she sometimes uses an apposite image to make a point – a split screen image of Doris Day and Rock Hudson in their respective bathtubs show how they complement one another.

Sankey is at her most persuasive describing the tradition in rom-coms of women sublimating their own interests for male pursuits – drinking and liking sports. The more a woman is like a man, the more he will like her. She uses the film How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days to make a point. In it, Andie (Kate Hudson) works on losing her partner Ben (Matthew McConaughey) by introducing him to her feminine world, in order to discomfort him. This being a ‘rom-com’, they do not split up. The film is based on a study of male-female behaviours by Michele Alexander and Jeannie Long and is better described as a modernist ‘rom-com’ that co-opts self-help and self-realization books to reinforce old stereotypes. I confess I tended to avoid movies with ‘how, what, where, why’ in the movie title, since they are not a guarantee of quality. They promise to answer a question, but you are never satisfied. I make an exception for ‘when’ – When Harry met Sally, When Saturday Comes – it is a more reliable interrogative, for the most part.

Sankey also makes us feel sorry for Cameron Diaz for having to sing ‘that’ song in The Sweetest Thing in a cafeteria setting (‘you’re too big to fit in here’). I believe she should get compensation every time it is played. The film’s screenwriter, Nancy Pimental, did not have control over the movie’s tone – every gross-out gag (including Diaz’s encounter with a penis in a glory hole) fell flat. According to the American magazine, Entertainment Weekly, the film has a cult following, but I am yet to be convinced it is a good bad movie.

A big part of the Hollywood ‘rom-com’ is the declaration, when the male lead realises that he has made a big mistake and admits his true feelings, usually in the rain or some unusual location. Commentators remake that guys really do make that declaration ‘but they never really say what I wanted them to say’. The point of the declaration is that the kiss stops men from talking because what they say is squeaky bottom embarrassing.

In an interesting diversion, Sankey notes that romantic comedies do not win Academy Awards except when they are in disguise. Silver Linings Playbook is the example, given the veneer of seriousness by the personality disorder experienced by its male protagonist, Pat Solitano (Bradley Cooper) and its references to suicide. Many of the tropes of the ‘rom-com’ are present, including the declaration but they are underpinned with dance, betting and OCD. It was the film that launched Cooper as a romantic lead, exploited in his self-directed A Star is Born remake.

Praise is heaped on movies Sankey did not see on first release – Saving Face directed by Alice Wu and Just Wright directed by Sanaa Hamri as well as the lesbian romantic comedy Kissing Jessica Stein. For the most part, Sankey focuses on the ‘romantic’ part rather than the comedy. She has a good take-down of the psychotic behaviour of Sandra Bullock’s character in While You Were Sleeping, in which a lonely subway teller pretends to be the fiancée of a businessman (Peter Gallagher) in a coma. Look at the lies she tells to insinuate herself into a man’s life. Sankey does not really explore what a good romantic comedy looks like, though she singles out Ruby Sparks and The Big Sick as interesting contributions to the genre.

There is a reason that Sankey shows more romance than comedy – she wants her contributors to add the wit and wisdom. But she does not really account for why snarky commentators who recognise that the ‘rom-com’ is junk food really believe that the kiss justifies the means. Plus, she does not offer the essential ingredients of a ‘guilt-free’ romantic comedy, the one that we can enjoy without believing that it peddles nonsense. I can suggest an answer. It is the comedy bit of the genre that displaces realism and also gives us pleasure – those inappropriate situations in which one or other lover finds themselves in, having to climb out of a window after being in a room that would compromise their chance of happiness. Displacements are the source of comedy.

The more real a romance is, the less funny it is. However, the comedy part is essential. Why? Because none of us really believes that there is just one person who will complete us or be the perfect soul mate. We do not make love, we make do. The essence of a good relationship is compromise. Desire always comes into it as do partners who have a quality that we do not possess – so we want them for their ability to plumb or do the accounts. Of course, this does not make for escapist entertainment. Unreality with a piercing recognition factor is the essence of movie joy.

Reviewed on Mubi UK streaming service, Saturday 16 May 2020