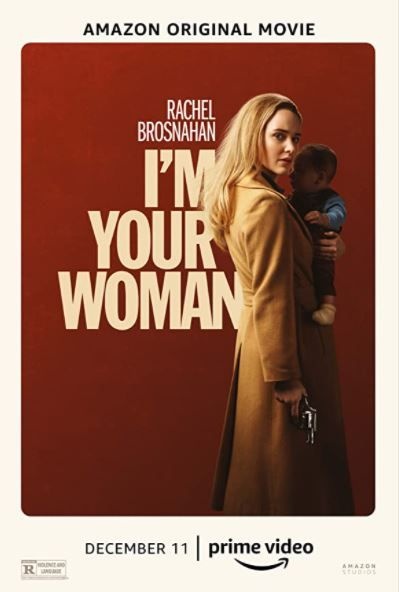

Pictured: Jean (Rachel Brosnahan) with her new baby Harry in a scene from the thriller, 'I'm Your Woman', directed by Julia Hart from an original screenplay by Justin Horowitz and Julia Hart. Still courtesy of Amazon Prime

Julia Hart’s fourth feature film as director, I’m Your Woman, is conspicuous for its lack of swear words. Perhaps it is because Hart, who co-wrote the film with her husband, Justin Horowitz, had just made a film for Disney +, Stargirl, a teen romance starring America’s Got Talent winner Grace VanderWaal who at one point plays the ukulele at a football match. Maybe it is because Hart wanted to redefine the 1970s thriller, the decade in which the film is set. Maybe it is because with cinemas being closed during the Covid pandemic, film is turning into television – and not cable television with few holds barred but television suitable for general audiences. This is not to say there aren’t gunshots in I’m Your Woman – the main character, Jean (Rachel Brosnahan, best known for the Amazon Prime show The Marvellous Mrs Maizel) is married to a career criminal, Eddie (Bill Heck). However, the makers are intent on tackling some tropes.

When we first see Jean, she is lounging in the garden in new clothes, smoking a cigarette. How do we know they are new? Because, having put them on, Jean suddenly remembers to cut off the tags. One of them is particularly tricky. Jean marches inside to find a pair of scissors, looking in drawers and in her miniature vanity case. In the end, she uses a knife. Just then, Eddie arrives home carrying a baby, perhaps four months old. ‘Here’s our baby,’ he says. Jean is stunned. Her voice-over at the very start of the film – we hear her before we see her – explains that she tried to have a baby but couldn’t do so. Jean doesn’t ask questions like, ‘where did you get him?’ She accepts the baby speechlessly as if it were one more present, like the new clothes that she ‘looks good in’. Eddie, we discover in his few scenes, is a man of few words; most of those aren’t complimentary about Jean’s cooking - she burns the toast and cannot keep the yoke intact when frying an egg. Oh, and he won’t be home tonight. The doorbell rings. Three men enter, one with an extremely long beard, who greets Eddie as if about to wrestle him. As the men disappear to another room to talk business, Eddie slides a door shut.

At night, Jean is alarmed by a knock at the door. One of Eddie’s associates turns up. ‘Where’s Eddie?’ Jean asks. ‘I don’t know.’ ‘What are you doing in Eddie’s closet?’ The man empties a box full of cash into a bag. ‘You’ve got to go. Cal will look after you. Give him $10,000 but keep the rest. Get the kid.’ Cal (Arinzé Kene) is another associate of Eddie, of a sort. He has been tasked to keep her safe. He holds an umbrella over her as she holds the baby, now christened Harry (and played by twins Jameson and Justin Charles, with additional baby acting from Barrett Schaffer) and takes the bag. He takes her to a motel. They share a room. To ensure Harry doesn’t wander off, the baby is surrounded by a ring of towels – there is a lovely wake-up scene, in which Jean, lying on the floor, turns and the baby responds. The eggs in a diner put Jean’s to shame. Cal reveals little, only that they are heading for a house. ‘I want one near a park,’ Jean insists. She likes to take Harry out in a stroller, though in the one scene where we see her do this, she sits far away from other mothers and children, smoking a cigarette.

Pictured: Jean (Rachel Brosnahan) in the park with baby Harry in a scene from the 1970s set thriller, 'I'm Your Woman', directed by Julia Hart. Still courtesy of Amazon Prime

Cal assumes that Jean would want to breastfeed the baby. ‘I can go out,’ he insists. However, Jean can only bottle-feed him. Harry cries relentlessly. Cal silences him by putting a finger between the infant’s gums – the baby is teething. Jean is astounded by his natural technique. ‘You have kids?’ ‘No,’ says Cal after a beat. Later, we will discover this to be true.

They drive down a country road. Cal holds an unlit cigarette out of the car window. Jean notices this. Cal won’t light his cigarette because it is bad for him. Instead, he simply imitates the gesture of inhaling, putting the unlit cigarette to his lips. The gesture is representative of Cal’s role in the story – he’s not quite there – just as Jean’s failure to cook eggs well is a metaphor for her infertility. An unlit cigarette has other connotations. Cal is withholding what makes him tick. He’s not brooding in a conventional sense, where each intake of nicotine pacifies raging thoughts. Instead, he’s putting on a show in order that Jean doesn’t ask him about other stuff.

In another motel, Harry acquires a fever. ‘I need to take him to a hospital.’ ‘No people,’ Cal insists, adding, ‘which part of being on the run do you not understand?’ The bit where the wife of a criminal is not held responsible for her husband’s actions, perhaps. At any rate, Jean wins. In hospital, Harry sleeps in a transparent, incubator type box. Jean sits next to him. Cal is seated near a window. He peeps through some blinds. Cops. In a British TV show of the 1970s, Cal might have said, ‘we need to leg it – the fuzz is coming.’ Jean might have responded: ‘what you bleedin’ talking about?’ At any rate, Cal makes the point through gestures. Jean lifts Harry out of his crib; Cal covers the baby with a blanket. They walk conspicuously down a corridor. The receptionist calls to them ‘Sir? Ma’am?’ They carry on walking. Just a mixed-race couple going about their business, la de da. They are close to the exit. They pass some cops. Jean bumps into a guy. They get to their car – they still have the bag of cash. Phew.

They drive until they reach a clearing where they all can rest. A cop awakens them. ‘Get out of the car.’ Cal raises his hands and does so. ‘You too ma’am.’ Jean, holding Harry, follows. ‘Are you sure this man isn’t bothering you? Who is he?’ ‘He’s my husband,’ Jean says quickly. ‘Why are you sleeping in the car?’ ‘We were on our way to our new home and wanted to drive through the night but then – what time was it?’ Jean entreats Cal to play along. ‘One or Two AM,’ Cal adds. ‘One or Two AM, the baby was tired. I thought we all should sleep. You have kids?’ The policeman nods. ‘You know how mothers can be.’ The policeman lets them go. As they drive away, Jean remarks. ‘I can’t believe I could lie so easily.’ Cal is in shock. He adds, ‘I made a white baby.’

Pictured: 'You eating those eggs?' Cal (Arinzé Kene) and Jean (Rachel Brosnahan) in a scene from the 1970s-set thriller, 'I'm Your Woman', written by Julia Hart and Justin Horowitz and directed by Hart. Still courtesy of Amazon Prime.

They eventually reach their destination, a home used by a member of the organization. The fridge is full. There are eggs, bread, diapers, milk, TV dinners. In other words, no reason to go out. There is a stroller, but no park. Before Jean can react to the news, Cal is out the door, but not before telling her about the pink telephone. ‘If there is an emergency, take the telephone out of the drawer, plug it in and call this number.’ After he leaves and we get the tasteful montage of domestic life minus diaper changing – feeding the baby, falling asleep in front of the television, going for a night time stroll, eating food served in tin foil – Jean prepares breakfast and still splits the yoke as she cracks an egg into the pan. She cracks one – no good. She tosses it. Cracks a second; it too is bad. Then she starts throwing the eggs against the kitchen wall. Remember - it is not her kitchen. Then the doorbell rings.

It is Evelyn (Marceline Hugot), her neighbour from two doors down who has brought some flowers. Her husband passed. She’s alone. She knew the previous occupants. ‘What’s your name?’ ‘Mary,’ Jean lies. ‘And the baby?’ ‘Harry.’ ‘Oh, of course – Mary and Harry,’ says Evelyn as if the two names go together. Well Jean wasn’t going to say, ‘Mary and Jesus.’ Evelyn invites Jean to call on her if she needs anything. Jean, of course, remembers Cal’s advice: ‘no people. People ask questions.’

Evelyn does indeed call again at night, bringing wine and a pot roast. However, when Evelyn asks, ‘where is the bathroom?’ Jean gets suspicious. ‘I thought you’ve been here before and knew where the bathroom was.’ ‘Of course, I do,’ Evelyn apologises. As Evelyn climbs the stairs, Jean’s anxiety increases. Jean stands up, knocking over a glass, and calls to Evelyn. Evelyn reappears on the stairs. ‘Are you all right, dear?’ she asks. Jean is glad to see her leave.

But during another night, Jean notices that her front door is open. She grabs the baby, plugs in the pink telephone, takes it into a closet, hunkers down and dials. She calls the number twice and gets the engaged signal. So much for an emergency number. She then dashes out of the closet and makes her way barefoot to Evelyn’s house. The door is open. Jean pushes it. She is greeted by two men. Evelyn is tied to a chair. Her face is bruised. The men have guns and one question. ‘Where’s Eddie?’

What happens next is a surprise. Evelyn finds herself on the run again with no money and ending up in a log cabin with a hiding place underneath the table.

I’m Your Woman has some terrific moments, notably a car chase somewhere in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in which all the vehicles, both parked and on the street, are 1970s models. That must have taken some doing. There is also a scene is a discotheque, the Foxden, where tens of revellers flee from the dancefloor after shots are fired, then flee back in the other direction. (You can practically hear the Second Assistant Director giving them instructions, as Jean/Brosnahan cowers in a telephone booth.) Jean makes some uncomfortable discoveries about her husband, breaks down in a laundromat, where an elderly woman puts down her knitting and reassures her and another woman brings a blanket, and learns to fire a gun. Jean also meets Teri (Marsha Stephanie Blake), young Paul (De’Mauri Parks) and old Art (veteran actor Frankie Faison – he played Coconut Sid in Do the Right Thing; confession, I don’t remember Coconut Sid).

With co-writer and co-producer Horowitz, Hart succeeds in constructing a thriller where the main character is never at the centre of what is going on. Jean isn’t exactly passive. However, minding a child she may have to give back (‘I think about his mother all the time’, she confesses) reduces her options. The imperative to flee as well as the responsibility to care for a child limit Jean’s ability to be introspective. We know Jean has a sister – ‘no sister’, warns Cal in his ‘stay away from people’ speech - but we don’t know why Jean would choose to stay with a criminal. ‘I know he steals, but Eddie is no killer,’ Jean says at one point. ‘He is a killer,’ she is told. Hart also doesn’t give us a scene where the married couple address their relationship. Shooting and car chases intervene.

Hart’s intention is clearly to take a character who would be marginal in a conventional male dominated crime thriller and tell her story instead. The film, running two hours in length (I’ve only related half the story) does what good thrillers should do, surprise us and delight us. The best scene has Jean explain how she makes Harry laugh, singing ‘(You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman’ (by Aretha Franklin) and exaggerating the harrups. Hart follows this moment by playing Franklin’s version of ‘Natural Woman’ over a driving montage. The scene works because Brosnahan makes us laugh – her role is otherwise joyless.

Does the plot make a whole heap of sense? I have my doubts. Does the film show a character who develops? Not conventionally. By the end, Jean, a woman told by her husband that she is not allowed to drive, takes the wheel. This is the third metaphor after cigarettes that aren’t smoked and broken yokes. The first two metaphors prepare us for the third one. Hart replaces bad language with visual language (of a sort). She also brings in Saint Francis – we learn casually that Jean was raised as a Catholic.

What of the title, taken from the Michael Mann film, Thief? (‘I’m your woman and you’re my man.’) It defines Jean as an appendage of Eddie. Only very slowly do we discover what she is capable of (and not just lying). In part, she is made by her (criminal) environment. Jean does not gain any gratification from her transgressions. They are necessary for her survival. In this sense they sit outside a moral imperative. There is one killing (not by Jean) that strikes us the wrong way and the film doesn’t end with Jean handing over the baby to the authorities. There is the suggestion in this gently subversive film that we need to re-think our moral positions, especially towards the Ten Commandments (bearing false witness and one other).

Finally, I commend the score by Aska Matsumiya, very reminiscent of David Shire’s music for The Conversation but by no means a shallow rip-off.

Reviewed on Saturday 5 December 2020 courtesy of Amazon Prime Video (UK)