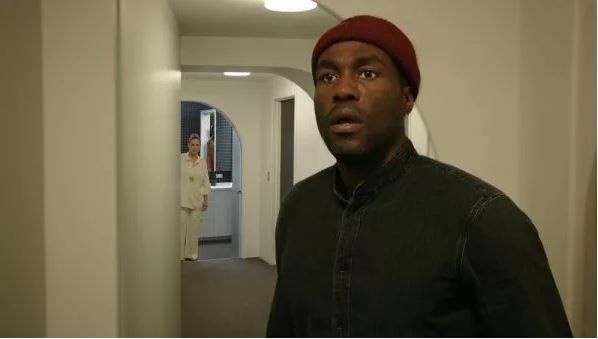

Pictured: Hot new artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul Mateen II) gets a surprise in an art critic's apartment - faux Rothko paintings - in a scene from the reboot-sequel, 'Candyman', co-written and directed by Nia DaCosta. Still courtesy of Universal Pictures (Monkeypaw Productions)

Contains spoilers

Co-writer-director Nia DaCosta’s reboot-sequel, Candyman, is a literate horror movie, if not entirely a smart one. At its heart, it tells a variation of the story of an artist, Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul Mateen II) who sells his soul to the Devil. There is a bee sting and slow disfigurement. Slowly but surely Anthony becomes the titular figure, with the finishing touch, a hook for a hand, administered in a surprising left-field way. Meanwhile, equally surprising, he is not associated with a series of deaths of those who took the Candyman challenge: to say Candyman’s name five times in front of a mirror. This invariably ends with the spectral Candyman, the ghost of a mutilated African American appearing the material world and hacking to death all those who summoned him. Anything for an eternity’s sleep.

Candyman first featured in a story, ‘The Forbidden’, written by British author Clive Barker, about a photographer, Helen, who becomes fascinated by neighbourhood graffiti on a Liverpool housing estate and is determined to uncover its origin. In 1992, for his third and most commercially successful feature, British director Bernard Rose transposed the action to a Chicago housing project, Cabrini-Green and cast Virginia Madsen as graduate student Helen Lyle (surname taken from the sugar company, Tate and Lyle) and Tony Todd as the titular Candyman. A movie legend was born. Todd appeared in two sequels, Farewell to the Flesh (1995) and Candyman: Day of the Dead (1999), the latter a straight-to-video release that also features an artist as a protagonist.

If I had looked at the credits of the original film before seeing the reboot-sequel, I would have noted that one cast member, Vanessa Williams, has returned, as Anne-Marie McCoy, Anthony’s mother. Anthony has no memory of it, but he is tied to the Candyman mythology. His mother told him that he was born on the North Side of the city, but he went he goes to the hospital on the South Side, he is told (somewhat improbably) ‘welcome home’.

I always found the plots of Clive Barker’s movie adaptations somewhat immemorable, mainly because you become more invested in the monster than a human protagonist. I recall Pinhead in the 1987 film Hellraiser, but very little of the film’s story. Same with the 1992 Candyman. I had no memory of a two-year-old child taken to a fire by way of human sacrifice in the film’s climax. DaCosta references the original film by use of shadow puppets – they occupy half the screen during the end credits and its worth staying to watch them for sheer aesthetic pleasure. There is a photograph of Virginia Madsen as Helen. You also hear her voice. However, DaCosta agreed with her co-writer and producer Jordan Peele (no slouch in the racial horror genre) than she would not use any original footage in order to control the film’s look.

Initially, I wasn’t sure whether the mirror image of the various film logos (Universal, Bron, Monkeypaw Productions) would resonate with the audience. The Leslie Bricusse ‘Candyman’ song from Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory is played in a steadily distorted way in the opening credits to remind the viewer where Barker got his inspiration – and what the horror writer wanted to subvert, that is, the idea of a stranger giving out sweets (candies) being somehow nice. Then we are taken back to Cabrini-Green housing project in 1977, with a young boy on his way to the laundry. He is asked by police in a parked car ‘have you seen this man?’ The boy shakes his head, drops a sock, picks it up, then loses another sock. One cop notices and shakes his head. Inside the building, the boy makes his way to the basement to the washing machines, deposits the laundry and switches the machine on (no detergent, no conditioner, nothing). Stepping out of the laundry room, he notices on the wall what appears to be black paint. However, it is actually the pitch-black inside of a cavity wall out of which is thrown a sweet. Stepping out of the cavity is a trenchcoated figure. The boy screams. The police enter the building. Then we hear louder screams. The boy stands on the stairs with his back to the basement, holding the wrapped candy whilst the police (off camera) brutalise the trenchcoated man.

Cut – after upside travelling shots of modern Chicago – to 2019. Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) has brought his new boyfriend, Grady (Kyle Kaminsky) to visit his sister, art curator Brianna (Teyonah Parris) who lives with stalled artist, Anthony. Anthony has always been confrontational about the treatment of black Americans in his work – one of his paintings features a white noose superimposed over an African American face. Lately, he has been uninspired. After complaining that Anthony is leeching off his sister, Troy decides the light some candles and tell a ghost story rooted in the now gentrified neighbourhood in which they live. Curious – an artist is defined by curiosity – Anthony visits the derelict, sealed-off remains of the housing project, cutting an imposing figure in his longshoreman-style red woollen cap, grey top, denim jeans and Converse ™ sneakers. He flinches as a police car sounds its siren, hoping not to get spotted. Anthony is seen by William Burke (Colman Domingo), carrying two cases, who explains that the police are ever present. Anthony helps him carry his heavy load, accompanying William back to the laundromat where he works. Only later do we discover that William is the young boy that we saw at the beginning - though the laundromat setting should have been a giveaway. He tells Anthony about Helen Lyle, and sweet wrappers that contained razor blades and Anthony borrows a laundromat-branded pen to take notes.

Walking on a patch of grass, having looked at the side of a church whose wall had been covered by white paint, Anthony is stung by a bee. That’s when his problems really start.

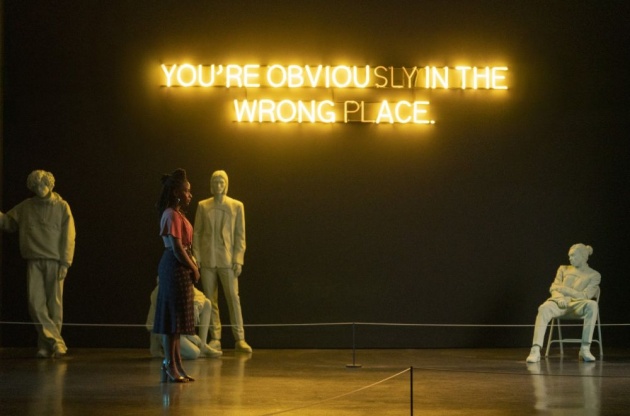

Pictured: Art for art's sake. Brianna (Teyonah Parris) visits a hipster gallery in a scene from co-writer-director Nia DaCosta's sequel-reboot, 'Candyman'. Still courtesy of Universal Pictures / Monkeypaw Productions

DaCosta portrays gentrification as a problem – forcing poor people out of sub-standard housing, then making rich folks fix it up. We aren’t introduced to the victims of gentrification – families broken up or made homeless. In the UK, gentrification is partially caused by turning single family houses into flats, usually after the death of the principal tenant. DaCosta mentions the Chicago version – low-rents attracting artists, a different type of resident, and changing the demographic. Invariably, gentrification involves the destruction of local businesses as the new residents open hipster coffee bars, bicycle repair shops and take-aways that sell square pizzas. (I’ve actually described the businesses at the bottom of my former street in North London.)

Yet isn’t this just a hipster, gentrified remake of Candyman with its gently satirical, but ultimately loving view of ‘worthy’ artists, and discrete use of horror? There is an element of parody in the group show, ‘A Fickle Sonance’ where Anthony displays his installation, ‘Say My Name’, a title that has another association – acknowledging those African Americans shot dead by policemen but here referring to Candyman (saying his name five times). DaCosta doesn’t give Anthony the awareness of the other association with the title even though she is aware of it. I found this somewhat surprising, since Anthony is sensitive to racial violence. ‘A Fickle Sonance’ is actually the title of an album by alto saxophonist Jackie McLean, released in 1961 (thank you, search engine). I guess DaCosta liked the title.

DaCosta follows familiar horror beats but doesn’t immediately give us the pay-off we expect. She will build suspense but then cut to something else. The killing of a white art critic occurs in long shot, seen through a window with the camera tracking backwards, after Anthony cuts short her interview. He senses the presence of Candyman. The art critic’s house is full of faux-Rothko paintings – a rectangle of one colour above a smaller rectangle of another colour. This is a subtle comment on colour imbalance in the world. All the doors in the apartment have curved tops as if like the inside of a futuristic spaceship – or a space vessel from a television series. I cannot emphasise enough the glut of visual pleasures that the film offers.

There is intentional humour too. Anthony visits a library and ignores the chatter of a young and (presumably) lonely female clerk who is glad to answer a question. His treatment of her is unintentionally cruel. Anthony has his own meltdown in the mirrored library elevator, which wobbles between 2 and 3 (just like the original Candyman series). The killing of a gallery owner during an attempted seduction is humorous too. He had fastened his belt to his lover, who dared to repeat Candyman’s name five times; now she has trouble getting away. Brianna discovers their bodies and is devastated. Yet, barely a few days later, she is having dinner with an influential New York gallery owner, naturally depicted as a fey Truman Capote-type. Admittedly, Brianna had been traumatised by horror before. Her artist father jumped from a window telling his daughter that he could fly.

Pictured: Young Brianna (Hannah Love Jones) sees her father Gil Cartwright (Cedric Mays) for the latest time in co-writer-director Nia DaCosta's reboot-sequel, 'Candyman'. Still courtesy of Universal Pictures / Monkeypaw Productions

DaCosta is critical of the art critic Finley Stephens (Rebecca Spence) who at first dismisses Anthony’s installation as obvious and points out that he is one of the principal beneficiaries of gentrification but later wants to interview him after his artwork inspired a murder. (I would have thought that the police would have called him first.) Finley is an object of satire. Her death is a comic-aesthetic punchline, resembling a sequence from The Invisible Man - Candyman is only visible in mirrors.

Most films about spirits released unintentionally by cocksure future murder victims usually climax with an attempt to put the monster back in the bottle. Candyman is different. Instead, the hook-handed killer is summoned to get one of the characters out of a bind and to take on the local police, substitutes for those who tortured him. It shows that DaCosta entirely understands the ‘Say My Name’ title – visiting vengeance for the long litany of racially motivated killings by police officers. This makes DaCosta’s film socially relevant, if not particularly subtle, but also has nothing to do with gentrification. Indeed, she has to break one of the rules of the movie. The character summoning Candyman ought to be killed but isn’t. In the final image of the movie, another cast member from the original makes a belated return.

DaCosta doesn’t have enough murder scenes to sustain a movie, so she has a mixed-race group of schoolgirls say Candyman’s name in the ladies’ room. A girl not part of the ritual witnesses the horror. She may indeed be the inspiration for a sequel if anyone dares make a fifth Candyman movie.

Reviewed at Ashford Cineworld Screen Ten, Kent, Saturday 4 September 2021. 18:20 screening