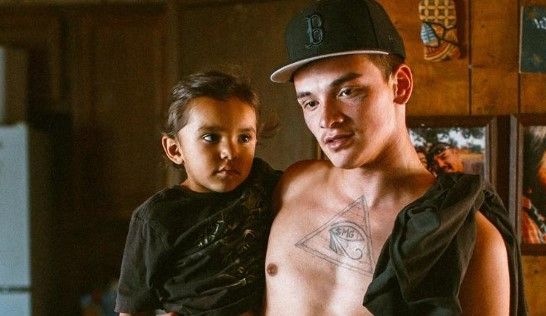

Pictured: Holding one of his two children, Bill (Jojo Bapteise Whiting) puts another scheme into operation in a scene from the 2022 American film, 'War Pony', co-written with Bill Reddy and Franklin Sioux Bob and co-directed by Gina Gammell and Riley Keough. Still courtesy of Protagonist Film Sales / Felix Culpa

Seven years after actress Riley Keough met some Reservation kids whilst working on American Honey, War Pony, her film about two young Lakota Ogala boys, co-directed by Gina Gammell and co-written by Bill Reddy and Franklin Sioux Bob, has reached the screen. On the one hand, it is commendable that the drama, set on the Pine Ridge Reservation, showcases a cast of young Native Americans. We’re a long way from Lou Diamond Phillips playing Officer Jim Chee of the Navajo police in Errol Morris’ film, The Dark Wind back in 1991 or Michael Apted’s 1992 film Thunderheart, in which Val Kilmer played a mixed heritage cop. (What is it with Native Americans and crime drama?) Films like Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves celebrated the dignity of Native Americans but ultimately put the white protagonist centre stage. Native American filmmakers such as Chris Eyre, Billy Luther and Sydney Freeland don’t get a huge amount of exposure for their work – Freeland is perhaps the most prolific, with an impressive list of credits on TV series such as Reservation Dogs on which she worked as a staff writer and Fear the Walking Dead. On the other hand, this is a film that doesn’t celebrate a thriving community. Characters fall foul of the law, sell drugs, and dodge parenting responsibilities.

Gammell and Keough use their influence to tell a story that otherwise doesn’t get much exposure internationally – America doesn’t want to acknowledge the land rights issue, in which the amount of land allotted to Native American tribes was cut from 138 million acres in 1887 to 56 million acres, currently held by the Federal Government in trust, with specific rules governing mineral extraction. For comparison, the US has nearly 1.9 billion acres in land (2.43 billion acres including water); Native Americans occupy 3% of it. We hear about Native American-owned casinos, but Native Americans have no stake in corporate America and comparatively little visibility in national government.

The misleading title to one side, War Pony put me in mind of Larry Clark’s Kids or Crystal Mozelle’s documentary, The Wolfpack, the latter about a group of kids locked up in an apartment in New York City entertaining themselves by recreating movies watched on TV. Essentially, the young characters are in view but unseen, fending for themselves from lightly stocked refrigerators. The big difference is, in Brooklyn, you don’t get stared down by a bison.

Our principal viewpoint character is Bill (Jojo Bapteise Whiting), early twenties, heavily tattooed, resembles a young Justin Timberlake; the camera likes him. He has two young sons from different women but isn’t raising either of them, instead living with an older relative. At the start of the film, he gets a call. His ‘baby mama’, Carly – call tone ‘pick up the phone, b-ch!’ - is in jail, following a traffic violation. She needs $400 for bail. Bill doesn’t have it – he doesn’t have a job. He does however have a poodle tied to the front porch ready to return to its owner.

On his way, he is stopped in his tracks by a bison, the animal equivalent of a four-wheel cruiser, minding its biz, emanating a ‘what you looking at’ vibe. The face-off is brief – middle of the road, what do you do? Crossing his path but heading in a different direction – but perhaps in the same direction, lifestyle-wise – is Matho (LaDainian Crazy Thunder), a twelve-year-old high schooler, bobbing in his T-shirt, hanging with three friends. Matho has a drug dealer for a dad; a man who looks young enough to look like Matho’s older brother. Before we leave Bill to follow Matho, we see Bill asking some kids if they want to buy a Playstation Four. ‘No.’ ‘Wanna buy this dog?’ ‘No.’ Can we blame a young man for trying?

Bill has a plot; Matho a set of circumstances. We see him in school, writing a note to a female classmate – she writes back referring to him as ‘ugly’. Matho sells small amounts of his father’s product; like Bill he’s a hustler. The dollars in his pocket aren’t enough for ice pops all round, but an aunt who pops into the store as he is about to leave has him covered.

Pictured: Matho (LaDainian Crazy Thunder, second from left, red t-shirt) and buddies in a scene from the 2022 Pine Ridge Reservation-set film, 'War Pony' co-directed by Gina Gammell and Riley Keough. Still courtesy of Protagonist Film Sales / Felix Culpa

In a few short scenes, Gammell and Keough establish the milieu. The houses are clapboard, have double doors. People are known; hospitality is offered with a resigned pragmatism. Better to have a kid off the street than on it. Arrogance is a luxury. Everyone recognises that life is a struggle.

The cross-cutting takes some getting used to. I didn’t want to spend time with Matho; I wanted Bill’s plot. The point of the film is that the two protagonists are the same side of a double-headed coin that you can’t spend in a store. Bill returns the dog with a buddy in tow but doesn’t get a finder’s fee. Instead, an offer. He can buy the dog and use it for breeding. (As his two sons attest, he’s good for that.) Of course, he is obliged to find bail money, but it is hard to come by. In a car, possibly borrowed, he cuts a break. There is a white guy on the road, Tim (Sprague Hollander), whose truck has broken down. He needs a lift. Bill negotiates a price. Tim agrees. When he arrives at Tim’s well-appointed estate, the deal is changed. Tim has another job for him, to change the tyre on his truck and drive the woman in it home. The sudden revelation that there was a passenger left behind is shocking. I immediately wanted a scene where Bill talks to her and learns why she went with Bill, whom we discover to be married. However, Gammell and Keough eschew this. There is no coverage of the journey back. Instead, the focus is on Bill taking up a job opportunity with Tim, working on his turkey farm.

Bill joins Tim and his wife, Allison (Ashley Shelton) for a drink. From the moment he meets her, she gazes at him attentively. Bill gulps the red wine he is given, as if finishing the drink is the point of it. ‘You’re supposed to sip it to get the taste,’ he is told. The scene is rather crude; surely, he would have seen wine or heard about it. They have TV on the reservation; some kids are seen watching a Popeye cartoon. It’s not the only moment that feels false. Matho sells a guy some product that is counterfeit; the guy chases him. Matho is saved by his dad. Later, a character will be found dead in the creek. Later still, there is an act of retribution that is the film’s equivalent of a crowd-rousing moment, but in the context feels too reckless to be real; it belongs in a Hollywood movie, not a social-realist one. You appreciate Gammell and Keough’s attempt not to throw a pity party, but their approach doesn’t work.

Matho’s dad is the kind of guy who buys action figures for his collection rather than as toys for his son – another nudge in the chest. When he discovers that Matho has messed with his stash, he chokes him with a Darth Vader-style neck grip. Matho leaves home to live with another drug dealer. The woman, who has a lounge full of kids, has three rules, the first of which is ‘go to school’.

Can Matho manage that? Not really. We see him asleep at his desk, having taken something. He then flees security. The girl who replied to his note doesn’t want to know him. She won’t fall ‘for a kid who doesn’t finish High School’.

There is a rhythmic mid-movie montage that demonstrates a preference for Hollywood not indie movie cliché. It represents the lull before the storm. Matho stashes money away and buys a card for his father, with the words, ‘I’m sorry.’ He gets an unpleasant surprise.

Tim makes a crass comment: ‘if there weren’t women, we’d have no need for money’. I don’t agree that women demand a capitalist system. Allison’s friendliness extends to giving Bill some jewellery that she doesn’t wear any more as a gift for his girlfriend. This is one of the better scenes, illustrating the gap between the Native American and white worlds. The protagonists are also cut off from their ancestry. Matho is spoken to by an older man. ‘Sorry,’ he replies, ‘I don’t speak Lakota.’

There are other moments that suggest that behaviour breeds behaviour. After Matho is saved, he and his friends indulge in a mock fight, imitating the moves that we saw earlier. In general, there is very little violence in the film. Later he and his friends steal a car and drive it during the right down a country road. The sequence is fraught with tension. Matho at the wheel takes his eye off the road and they crash. Fortunately, the four kids emerge unharmed.

Carly does indeed get out of jail, no thanks to Bill, and has little to say. The climax involves a Hallowe’en party at Tim’s house. Bill is invited to bring some friends who serve as waiters. This appears to be the moment in which he can finally sell his dog. He has one of his sons with him and offers to babysit the other in order than his ex can have a night out. He then leaves them in a car with Beast, the poodle he aims to sell, and a box of puppies, promising that he’ll be back in ten minutes. It’s a long ten minutes. The first time he checks on them, they are fine. The second time, the car door is open. There is a gunshot.

Would one of the party guests really dress as a Native American at Hallowe’en to court Bill and his friends’ disapproval? It is certainly another nudge towards sympathising with them. Bill is treated rather cruelly, Tim and his friends each telling him that they have no desire to buy a dog. For her part, Allison knows that Tim is unfaithful. She tolerates it but is humiliated at the same time.

Gammell and Keough don’t have an ending. Sure, there’s the crowd-rousing moment in which Bill and his friends stick it to the man; maybe if there were no turkeys, we wouldn’t have money. There are turkeys everywhere, even sharing land with the bison. There is also the moment when Bill catches Matho breaking into his house. Instead of cursing him, he offers him a peanut butter sandwich that Matho gratefully eats; it is that culture of resigned hospitality, again.

War Pony elicited a positive response when screened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2022, but it is a wobbly debut, a movie that looks like it was saved in the edit rather than the realization of a well-crafted screenplay. For me, it felt like two movies in one rather than a satisfying whole. It has some strong moments but as a drama it is tonally uneven as if the writers saw social realism as a trap that they sought to swerve away from at the last minute – rather like Matho’s driving. A funeral cortege provides the most vivid image: a procession of cars zigzagging down a road accompanied by ululation. The opening image is of an elder Lakota Indian burning something, an image we return to near the end. Gammell and Keough celebrate the hard-won resilience of their characters but haven’t created a narrative about transformation. That 3% is something to be looked at.