Pictured: Dwarfed by followers, guilt-afflicted pensioner Harold Fry (Jim Broadbent, centre) continues on his five-hundred mile walk in painful shoes in the British film, 'The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry', written by Rachel Joyce, adapting her 2012 novel, and directed by Hettie Macdonald. Still courtesy of Entertainment One (eOne) (UK)

Eccentricity and self-mortification are two elements at play in director Hettie Macdonald’s film adaptation of Rachel Joyce’s very English novel The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. Jim Broadbent, an actor who has worked with Mike Leigh, Baz Luhrmann and Martin Scorsese, is typically unassuming as the titular Harold, a retired brewery worker living with his wife, Maureen (Penelope Wilton) in South Devon who decides to walk five hundred miles to Berwick-upon-Tweed to be reunited with a former colleague, Queenie Hennessy (Linda Bassett) who is dying from cancer. Unable to find the right words to respond to her letter, written on pink writing paper, he arrives at the conclusion that by walking to see her, he can keep her alive. We don’t know how long it will take Harold to get there, especially in the wrong sort of shoes, and whether Queenie will live to see him, but as with all road movies, it is the journey, not the destination, that is important. Joyce, who also wrote the screenplay, and Macdonald give a significant amount of screentime to Maureen, the wife left behind, furious with her husband and trying desperately to cope. Both Harold and his wife have different reasons to feel guilty, their ‘brilliant’ son David (Earl Cave) having struggled with mental health issues that lead to depression and substance abuse, suggested in a series of impressionistic flashbacks (the sound is turned down, the background out of focus). In spite of a wobbly mid-section, the drama moves us not once but twice. It is a film about showing that you care. It posits the necessity of uncritical faith. Faith is both the foundation of divisive religions and delusional pastimes (suicide pacts, Britain leaving the European Union) but also the driver behind ambition: that problems can be solved, that certain feelings are real.

The filmmakers walk a tightrope between the twee and the troubling. The first sound we hear is that of a vacuum cleaner. As we see Maureen hoover a carpet, we think briefly, ‘is Miele a good brand?’ The second sound is metal on ceramic, a spoon being used to stir a cup of tea. Domestic routines are a burden, but they structure our days. The absence of music on the soundtrack speaks (subtly) of a vacuum between husband and wife, Harold struggling to open an envelope and being given a butter knife by Maureen to aid him; the misuse of a butter knife is an equally subtle detail. Having read the letter, Harold attempts a reply, only the words are insufficient – as they almost always are – to convey a depth of feeling. He resolves to post his imperfect letter but keeps walking until he reaches a service station, where an employee (Nina Singh) with matching blue hair and fingernails – and a nose ring to underscore her punk credentials – tells him about belief helping to keep a relative alive. At this point, as occasionally happens in the film, the sun pops out from behind some clouds casting a light over the assistant who wears a name badge that reads ‘happy to help’; it may as well as read ‘catalyst’. Harold resolves to go for a long walk, meeting a variety of people along the way, whose lives he touches – or touch him – to a smaller or greater extent.

Where does self-mortification come in? Harold resolves to walk in flat shoes with very little arch support, although at some point we see the heel of one of them and note the lack of wear – details matter. He punishes his feet. He occasionally asks strangers for a glass of water, notably a farmer’s wife (Claire Rushbrook) in an early scene. At the start of his journey, he pays for his board. Forgetting to bring his mobile phone, he uses a phone box to call first the hospice looking after Queenie then his wife. After hearing his intentions, Maureen slams the phone down on him. She’s furious, visiting a doctor to explain that he has Alzheimer’s. ‘Has he been diagnosed?’ ‘Well, he forgets things,’ Maureen adds in exasperation. Harold’s shoes punish his feet. He relies on plasters. He is found by a Slovakian woman, Martina (Monika Gossmann) who takes him in. Joyce’s book was published in 2012, before the vote to leave the European Union. The film makes the point that Monika is a qualified doctor forced to clean toilets to make a living. ‘You should see the toilets,’ she adds. She washes his feet – a near religious act - and gives him a bed for the night, telling him, ‘you are my guest.’ She had a partner who left a year ago, after a woman and a child turned up. ‘I didn’t know him,’ she explains. ‘He’ll come back,’ Harold tells her in an attempt to console her, as if surprised that any man would leave a woman as kind as Monika. The next day, she confiscates his shoes to allow him to recuperate. ‘Back at five’, her note tells him. He spends the day tidying her garden, watched by her dog from inside the house. ‘David wanted a dog,’ he reflects. Eventually, Monika returns his shoes and offers him a knapsack in which to carry his toiletries.

Harold’s first encounter with a world seemingly very different from the one he imagined occurs when he sits in a café in Exeter St David’s when a man asks to share his table. The man explains that he has been meeting a younger man for some weeks. ‘Shall I continue?’ Looking vaguely terrified, Harold nods. ‘I used to lick his shoes,’ the man explains. ‘However I noticed that his trainers were worn out. The young man doesn’t speak much English. I want to buy him new trainers. What should I do?’ Astonished by his unexpected role as café confessor, Harold tells him to buy the trainers. The advice doesn’t appear to come from a place of understanding, rather an instinct to say the right thing.

One of the pleasures of watching a road movie is being told where you are in the country and nodding in recognition. Harold’s first acquaintance with a map is in Monika’s house. We get a sense of his route. Mostly though, he is framed with fields in the middle distance or else on a road without signage. The film is desperately short of signage. There are recurrent motifs. Harold will find himself in a town centre where a street entertainer performs in the background. The film gives way to folk music.

Pictured: 'How dare you walk five hundred miles? Your supper's gone cold.' Maureen (Penelope Wilton, right) berates her wander-must husband Harold (Jim Broadbent, left) in the drama, 'The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry', written by Rachel Joyce, adapting her 2012 novel, and directed by Hettie Macdonald. Still courtesy of Entertainment One (eOne) (UK)

Staring at the door to potential accommodation with something akin to dread and knowing that Maureen is concerned about the expense – ‘I’ll work to a budget,’ he tells her – Harold decides to sleep outdoors, first in an abandoned barn on some blocks of hay, then, finding a sleeping bag, in fields. He puts his some of his possessions in a jiffy envelope, including his bank cards, and sends them back to Maureen, who by now has told the truth to their neighbour Rex (Joseph Mydell). She feels the pain of abandonment, at one point pulling down net curtains in various rooms. At this point, Harold has become an unexpected celebrity, having told his story to a man in a pub who bought him a glass of lemonade and took his photograph. Strangely, Harold is unsurprised when a woman asks if he is Harold Fry. Soon he attracts one follower, a young man, Wilf (Daniel Frogson), who reminds him of his son, but who has given up pills and found religion, and a dog, then several followers who walk with him. It is at this point that the drama goes awry. Surely with all that help he would get to where he is going quicker. At one point, he receives a delivery of a dozen pizzas on the road. We are told that in one day he walked only one mile, on another even less. This doesn’t ring true. Going by road, he should be able to cover ten miles a day at a minimum – my walking speed is about four miles an hour. Harold’s support group are all given red tee-shirts that say ‘Pilgrim’. There is further media coverage. You expect Maureen to be interviewed and the hospice to be part of the story, but they aren’t. Harold himself is displaced by others.

Maureen surprises Harold during one of his stops and buys him a strawberry milkshake and some cake. By this time, he has been helping himself to farmer’s boxes and eating blackberries from bushes. Macdonald spares us his toilet habits. Maureen continues to be angry with him. He eventually realises that he has to abandon the group, though the dog continues to follow him. Wilf purloins the pendant he bought for Queenie at a gift shop – Harold also sends her postcards – but gives it back. It is clear that Wilf has lapsed back into taking pills.

Throughout Harold is plagued with flashbacks of his son, who is seen arguing with younger Harold, shaving his head in the bath and smoking in his room with an ashtray on his chest. At one point, Harold appears to see David in a town centre. The young man does not respond to his frantic calls. We discover the tragedy at the heart of Harold’s life, how he was consumed with anger and how Queenie saved him.

Does Harold make it to Berwick-upon-Tweed? It isn’t a spoiler to say that he does. However, his outburst of emotion in a café, bearing the sign ‘no begging’, is less about Queenie and more about his own sorrow. He is recognised, though in Berwick-upon-Tweed there is no welcoming committee.

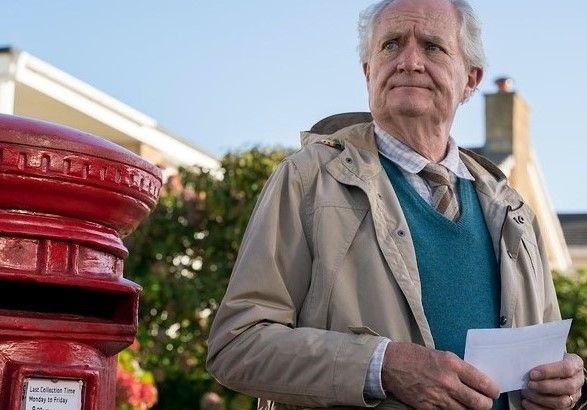

Pictured: Beset by 'dismal stories', according to the church hymn, Harold Fry (Jim Broadbent) ponders by a pillar box in the British film, 'The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry', written by Rachel Joyce, adapting her 2012 novel, and directed by Hettie Macdonald. Still courtesy of Entertainment One (eOne) (UK)

The film moves us partly out of Harold’s recognition of his own guilt and partly out of his debt to Queenie. The pendant he hangs on the window to her room reflects light, which is acknowledged. In a brief montage, we see that Harold has brought light – and life - to others, even though the garage girl confesses that she lied. Finally, Harold gets an invitation he cannot refuse.

At one point, he speaks to an American tourist, who asks if he has found religion. Harold’s faith – his constant chanting to himself – doesn’t acknowledge God. Macdonald presents him as a folk hero of sorts, though it is unlikely that his followers would be content to be abandoned - and not just because they would miss the free pizzas. The film celebrates the impulse to do good, yet it is released at a time when the British media demonises the small boats carrying migrants without visas across the English Channel from France, the media insisting upon the virtues of not following European law. The latest campaign alleges a new law that will make toilet paper scarce, as if Europeans rely on something else. The England of Joyce’s book differs from the country a decade later; Macdonald’s film is practically a cartoon. The film would have been better positioned as a period piece.

At several points, Harold’s wounded, frightened, hair speckled face fills the screen. We see his pain and fear. Broadbent radiates vulnerability, no more so than when he washes himself by a river. Yet the film radiates a belief in people, not entirely borne out by the schism of the EU Referendum. There is a deep human need to believe in others, that eventually they’ll do the right thing. The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry exudes that belief.

Reviewed at Cineworld Dover, Southern England, Screen Three, Monday 1st May 2023, 12:00 screening