Pictured: Concerned about the family business, Mina (Lubna Azabal) and her 'maalem' husband Halim (Saleh Bakri) in a scene from the Moroccan film, 'The Blue Caftan', co-written and directed by Maryam Touzani. Still courtesy of New Wave Films (UK) / Strand Releasing (US)

Moroccan co-writer-director Maryam Touzani (Adam) specialises in films in which characters find comfort in enclosed spaces. Open streets invite suspicious looks, disdainful comments and, worse, the police. Privately, people can smile and be liberated from the fear of censure. Would they be happier still if such censure didn’t exist? Perhaps. But Touzani doesn’t directly challenge the status quo, rather shows defiance in small gestures.

Morocco has been described in seemingly contradictory terms as a liberalized authoritarian country. Ruled by King Mohamed VI since 1999, the country experienced protests in the spring of 2011 in common with neighbouring countries such as Egypt and Tunisia. These led to few fatalities – reportedly, only one - as the King deftly instituted reforms following a heavily stage-managed referendum. His success was in no small measure due to his co-opting the socially marginalised Amazigh (Berber) population. Protests are broadly tolerated, though demonstrations take place outside parliament rather than in front of the Royal Palace. In spite of carefully engineered reform, resulting in some degree of economic stability, the root causes of the protests have never been fully addressed. Youth unemployment, especially amongst Amazighs, remains troublingly high. Corruption is also an issue. That said, the Moroccan football team is a source of national pride, ranked by the football authority FIFA in December 2022 as the 11th best team in the world and top among North African nations.

Touzani’s second film as director, The Blue Caftan, co-written by her film director husband, Nabil Ayouch (Casablanca Beats) is a loving story of a marriage between Halim (Saleh Bakri), a maalem or skilled artisan and his dying wife, Mina (Lubna Azabal) and their relationship with a young apprentice, Youssef (Ayoub Missioui). Halim’s work is prized. He repairs or creates caftans – a one-piece traditional dress – using dazzling fabric augmented by detailed and visually-pleasing coloured stitching that is intended to be noticed. In the film, Halim makes copious use of golden thread; Youssef spends his time preparing it.

The film begins (more or less) with Youssef, the latest in a series of apprentices, starting work, having waited outside Halim’s shuttered shop for an hour. There is plenty to do; Halim is behind on his orders. Youssef is unskilled in maalem practices. Halim shows him what to do. ‘Press down hard with the needle,’ he insists, the two men standing close together. In this film, the homoerotic charge isn’t a subtext – it is front and centre. After work, Halim goes to the hammam (steam bath) and associates with other men in private booths. A look is exchanged; another man follows him. In one scene, Touzani’s camera stays outside the booth, panning down to the feet of Halim and another man. One of the men turns around. Throughout, Touzani’s approach is suggestive. It feels daring for a film set in a country where Islam is the dominant religion.

For her part, Mina is devout. In a few scenes, we see her on a prayer mat. By day, her job is to take care of the customers, explaining why work cannot be completed by the customer’s timeline and offering to return the deposit. In the evening, she prepares meals. Occasionally, on a working day, we see life outside and a neighbour reacting to loud music being played. The streets are narrow and traversed by comparatively few people. Children aren’t out playing in groups.

In an early scene, a customer brings Halim an article of clothing that she wants him to repair – Halim’s customers are women, his supplier is a man. Halim explains that the work is beyond his skill. He once saw a Jewish maalem complete this kind of work. He offers to iron it for the customer instead. The customer agrees.

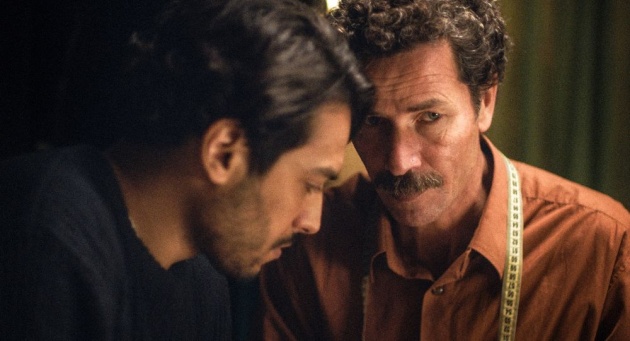

Pictured: 'Press down hard with the needle.' Youssef (Ayoub Missioui, left) receives instruction from 'maalem' Halim (Saleh Bakri, right) in a scene from the Moroccan film, 'The Blue Caftan', co-written and directed by Maryam Touzani. Still courtesy of New Wave Films (UK) / Strand Releasing (US)

Mina says nothing about Halim’s trips to the hammam. She fears that Youssef will leave, taking a better job as a delivery man. ‘No one wants to learn,’ she explains, having seen many apprentices come and go. Halim replies that if Youssef leaves, another man will take his place. Mina is not so sure.

The blue caftan of the title is worked on intermittently throughout the film. We see Halim stitch circles around the hem while Youssef prepares the thread outside; the workspace is claustrophobic. Mina is suspicious of Youssef and asks him for the pink satin. ‘I’ll find it,’ he tells her. ‘You won’t – it’s not there,’ she snaps, adding, ‘if you can’t find it, I’ll take it from your wages.’ ‘Do so then. I’m not a thief,’ Youssef replies. Tension between the two of them remains. We wonder if Mina suggested the crime so that Youssef will leave, observing – and perhaps being jealous of – his proximity to her husband. We find out that the pink satin was mislaid in a different way.

The titular clothing has symbolic value, as we discover in the film’s final scene. It is also coveted by others. A woman comes in asking Mina for a caftan. Mina shows her some fabrics. The woman is unimpressed. Noticing the blue caftan work-in-progress, she asks for it. ‘It’s for another customer,’ Mina tells her. ‘May I just see it?’ she asks. Mina agrees. The woman admires the colour. ‘I like the royal blue,’ she tells Mina. ‘It’s petroleum blue,’ Mina replies, offended. ‘Whatever the other woman is paying, I’ll pay more,’ the woman tells her. Mina refuses. The suggestion is that the business honours its contracts; only the customer can break it. The woman, whom we are later told is the wife of the district chief, leaves with a scowl. In their apartment, Mina and Halim replay the conversation in a jovial, mocking way, exaggerating the woman’s arrogance. They laugh together, something up to that point we have not observed, making the point that the woman would be paying for the caftan with bribes accepted by her husband.

Halim and Mina’s evening ritual involves Halim standing behind a seated Mina, helping her remove her top and change into her nightshirt. We see Mina’s naked back. This seems quite daring but is necessary to illustrate Mina’s frailty. Mina coughs. Halim offers to take her for a scan. ‘Pay 8,000 dirhams?’ Mina asks. ‘It won’t help.’ Mina previously received treatment, but the problem has not gone away. In one scene, Halim finds her collapsed on the floor. He helps her up. She insists that her condition is manageable, though it becomes apparent that it isn’t.

Before that point, Mina asks to be taken out by Halim. She would like to go to Café Moha and enjoy a mint tea with saffron. Halim is incredulous – not that we can quite tell his expression behind his thick moustache – but agrees. They take their seat among a group of men and place an order. The men are watching a game of football on a television that we don’t see. Mina stands up and shouts ‘goal!’ It was of course for the other side. The men grumble about Mina, whilst silently fuming that the goal was conceded.

On the way back, they are stopped by police and asked for papers. Halim provides his identity document. ‘What about you?’ ‘I don’t carry mine,’ Mina says defiantly. Halim is placatory, Mina outraged. ‘Do you have your marriage certificate,’ they are asked. ‘It is at home, close by. I can get it,’ says Halim. The police decide to let the couple off ‘this time’. At home, Mina is furious. ‘Why don’t you say anything?’ Halim doesn’t want to draw attention to himself. He is used to being discrete.

With Youssef this manifests itself in the shop. Youssef stands close to Halim. ‘I love you,’ he tells him openly, dropping the thread. Halim’s head is bowed. ‘Pick up the thread,’ he tells him quietly. ‘Pick up your own damned thread,’ Youssef cries before storming out. By this point, Mina is at home, ill. Before then a supplier comes to the shop and tells Mina that she had returned the pink satin that she had paid for by mistake. Youssef observes this conversation but says nothing. Mina does not mention it to him either, but her lapse in memory is indicative of her declining health.

With Mina now bed-ridden, and Youssef having quit, Halim stays at home with his wife, caring for her. Whatever she thinks of him, she still desires him. Touzani tests the bounds of Moroccan censorship by showing a love scene initiated by Mina, putting his hand on his chest, and massaging it before encouraging him to make love to her. The camera stays on their faces, not their bodies. Halim’s expression appears pained. This, we sense, is his duty as a husband.

‘My mother died in childbirth. My father hated me for being born,’ Halim explains by way of accounting for his homosexuality – seeking the love that he could never earn. This suggests that homosexuality develops in response to deep trauma. Halim and Mina get a surprise visitor – Youssef. He saw the shuttered shop and came to help, bringing Mina her beloved tangerines, the only food she appears to eat. In an earlier scene, she prepares a meal for Halim but doesn’t eat herself. In another scene still, we see rotten, fungus-covered tangerines, suggestive of Mina’s own decay as well as neglect. Mina’s attitude towards Youssef changes. She apologies for accusing him of taking the pink satin and explains her mistake. ‘I know,’ Youssef tells her. When a neighbouring shopkeeper starts playing music and another neighbour complains, Halim, Mina and Youssef start dancing together. It is at this point that Mina knows and accepts Youssef’s love for her husband and Halim’s love for the young man. Youssef pretends that he has kept the shop open. Mina tells him to make sure a customer pays before being supplied with the caftan; otherwise they will wait a year.

Pictured: Happiness behind closed doors. Youssef (Ayoub Missioui, left), Mina (Lubna Azabal, centre) and Halim (Saleh Bakri, right) in a scene from the Moroccan film, 'The Blue Caftan', co-written and directed by Maryam Touzani. Still courtesy of New Wave Films (UK) / Strand Releasing (US)

‘You are the most noble man I know,’ Mina tells Halim, referring to his craft and for staying with her. They have a business and a life, albeit with no children but are, in the final analysis, devoted to one another. In the finale of the film – in an admittedly predictable way – Halim displays the level of his devotion, and the true value of the blue caftan. In the very final scene, we return to Café Moha during the day.

The film’s only moment of explicit nudity occurs when Mina, during her change into a nightshirt reveals her breasts and evidence of a mastectomy. We understand that she has cancer and her struggle with it continues.

Touzani’s film is delicate and absorbing, with clear affection for the characters. We learn that Youssef grew up on the streets, supporting himself through a variety of jobs. He too lacks a father. We learn the cost of a slather of black soap – two dirhams – and the cost of a booth, 15 dirhams, indicating just what a sum 8,000 dirhams is to Mina and Halim. By the end if the film, I wasn’t emotionally moved but I did respond to the film’s warmth and generosity. The film is also visually pleasurable. Touzani’s director of photography, Virginie Surdej, makes us fall in love with the fabric and join Halim and Mina in scolding those who don’t respect the maalem’s craft. A young woman insists on having her silky caftan taken in even though it is supposed to hang from the body and be felt as it is worn, touching then not touching the skin. Such sensory pleasure is anathema to the customers who are only interested in how it looks, not how it feels. Reluctantly, Halim agrees to the request. For me, the delicate interplay and sympathy towards the characters was enough. I didn’t need to leave the cinema in buckets of tears.

During the question-and-answer session after the screening, which concluded with her young daughter grabbing the microphone and miaowing into it, Touzani explained that the film was not a sop to European audiences – ‘we have homosexuality in Morocco’ – and that it was based on a black caftan that Touzani had heard about. The film received support from the Moroccan Film Board, who were the first to invest. The Blue Caftan is being released in Moroccan cinemas uncut on June 7th. Evidence of liberal authoritarianism indeed.

Reviewed at Curzon Bloomsbury, Renoir Screen, Central London, Thursday 4 May 2023, 18:00 screening. With thanks to ‘Reclaim the Frame’