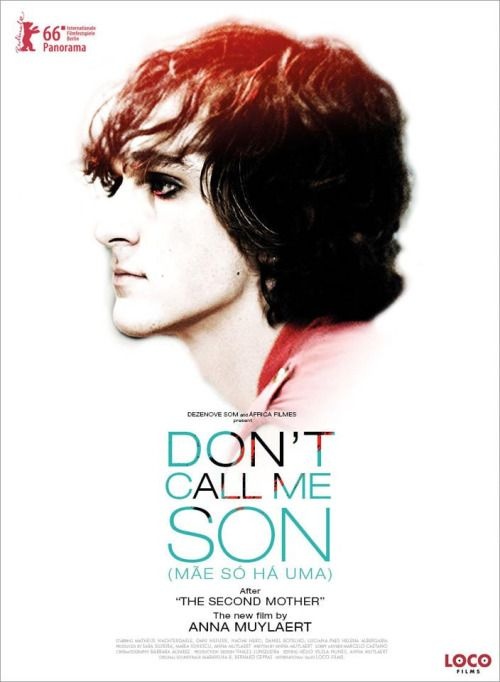

51 year old Brazilian writer-director Anna Muylaert (born 21 April 1964) is no overnight success. Her first feature, Durval Records (Durval Discos) was released in 2002. She didn’t become known internationally until the 2015 Berlin Film Festival premiere of The Second Mother (Que Horas Ela Volta), the story of a maid whose existence is disrupted by her teenage daughter coming to stay in the home of her employer. It is an absorbing study of shifting family dynamics and social mobility in modern Brazil, with a winning central performance from Regina Casé. Don’t Call Me Son (Mãe só há uma) is Muylaert’s follow-up, presented at the 2016 Berlinale. It is another story of family dynamics, but could not be more different.

Felipe (Naomi Nero) is an inattentive student who likes to wear women’s underwear. He likes girls, though when his girlfriend kisses him at a musical rehearsal, he draws the line. Unbeknownst to him, he is being watched. One evening, his (single) mother, Aracy (Daniela Nefussi) arrives home late –Felipe’s younger sister boils him an egg by way of taking care of him. Aracy doesn’t explain where she has been but then two men knock at the door and ask to speak to Felipe. There is something his mother hasn’t told him.

Felipe’s mother is arrested for having stolen him as a baby. He has been identified as Pierre, the long missing son of Matheus (Matheus Nachtergale) and Gloria (also played by Nefussi). He is ‘returned’ against his will to live with his family. Only he is a young man in transition, with a liking for women’s dresses.

The plot is the stuff of telenovelas. Where Don’t Call Me Son really scores is in the indictment of a family law system that does not allow adolescents in Felipe’s situation – his biological parents insist on calling him Pierre – being transitioned in to the life he has never known. He is cast against his will from one situation, where he is to some extent in control of the pace of finding his real (sexual) identity to another set-up entirely, where his actions provoke his biological parents. Moreover, Felipe doesn’t view his other mother as a criminal. He wants to continue their relationship even though she is in police custody.

An American TV movie might focus on the trial of Aracy, but Muylaert keeps her camera on Felipe’s extreme actions, choosing a dress rather than polo shirt in a clothes shop and going bowling in women’s clothing – to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, his ball constantly ends up in the gutter whilst his biological father sees metaphorical stars (hashtag Oscar So Right). That said Muylaert cannot – and does not – resolve the story. The film ends with Felipe dedicating himself to another quest.

Like The Second Mother, the title Don’t Call Me Son has two meanings. Not only does Felipe not want to be Matheus and Gloria’s son, though he doesn’t take this out on his younger biological brother, Joca (Daniel Botelho) but he doesn’t want to be thought of (in gender terms) as a boy. He is contrasted with Joca who has girlfriend issues with a 12 year old girl in his class. The young Joca discusses his relationship with the unseen girl in adult terms. He represents in extremis the pressure to be moulded into a heterosexual. Felipe teeters on the verge of being a good older brother to him but he is too unhappy to take young Joca in hand.

Don’t Call Me Son isn’t as satisfying as The Second Mother but it does have some good scenes. The story about a family’s struggle to get their son to love them has resonance. In the end, it is a person’s past, not their biology, that is the strongest contributor to their identity - nurture not nature.

Reviewed on Friday 19 February 2016, 20:00, Cinemaxx Berlin, 66th Berlinale (Berlin International Film Festival) – with thanks to the stranger who had just seen ‘A Quiet Passion’ and sold me his ticket