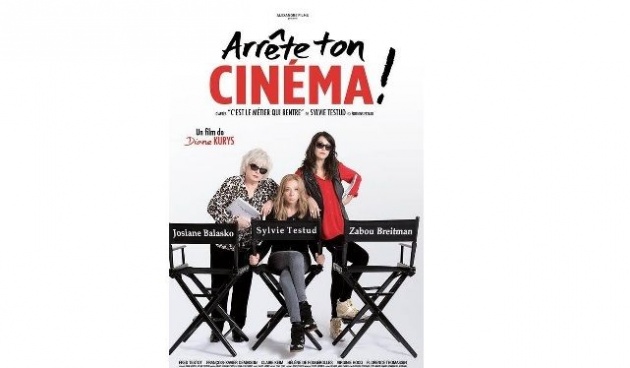

Arrête ton cinéma is the third collaboration between actress Sylvie Testud and veteran director Diane Kurys after 2008’s biopic Sagan and 2013’s Pour une Femme (For a Woman). Here, they have collaborated on the screenplay based on Testud’s book, ‘C’est le métier qui rentre’, a title that makes little sense in English: ‘It’s the job that fits’ or ‘it’s the job that returns’ but here more like ‘it’s the job that rebounds’; you take it on and it blows back in your face.

Testud plays Sybille, a successful in demand actress with an abiding desire to direct her own autobiographical screenplay about three sisters who discover who their father is whilst in hospital. Sybille signs a contract with JRRP whose initials (in French) stand for ‘I never flop’ – a motto more suited to the treatment for erectile dysfunction rather than a film company. Her agent, Jack (François-Xavier Demaison) tells her to stay away from the two women who run it (‘they’re crazy’) but Sybille climbs the marble staircase in their grand town house anyway. The producers, Ingrid (Zabou Breitman) and Brigitte (a silver-haired Josiane Balasko) are a couple who make impossible demands – the first draft of a screenplay in two weeks; we shoot in June. Their energy and forced enthusiasm is terrifying. Her agent warns her that JRRP is always being sued. Indeed, the company name is practically a guarantor of disappointment.

In Testud’s real experience, the producers were a male-female couple – she declined to name them, perhaps fearing a lawsuit herself. ‘But they are well known’ she told an audience in London. The comedy comes from Sybille’s inability to resist Ingrid and Brigitte’s increasingly desperate demands. Make no mistake: Ingrid is as bad as Brigitte.

After turning in her screenplay, missing out on vacation with her two children, Sybille is asked to make changes. Hospital is boring. What about a horse farm? So Sybille takes her lead actress Julie (Claire Keim) for riding lessons with predictably poor results; the horse throws her. Then Ingrid takes a look at the re-write (‘boring, boring, boring’) and asks her to change the sisters to escort girls. Sybille takes her husband Adrien (Fred Testot) to a pole dancing club near the Moulin Rouge and fends off an escort girl. They row afterwards. Imagine Sybille’s shock when she is awakened by sounds downstairs and sees her husband in the kitchen with the escort girl. But then the escort girl turns into Ingrid and it is just a dream.

Sybille’s two sisters work in a food van. One of them is quite pleased that the profession of the sisters keeps changing ‘so no one will recognise that it is us’. Kurys and Testud close down potential sources of conflict, as even Adrian learns to accept that Sybille will be making her film. The joke is that the content moves sharply away from an emotional story. Brigitte decides to name it ‘Pretty Girls’ (the title is English rather than French, the worst kind of insult) and the producers convince Sybille to shoot a pop video with the three actress to promote the film, set to a 1970’s disco song, ‘where are the women?’ by Patrick Juvet.

Testud has a physical presence best described as willowy – you might think of Alyson Hannigan (‘How I Met Your Mother’) when you see her. She looks like she has just stepped out of the shower, cold and trembling, with eyes that have seen if not ghosts then a lot of horror films. She is the opposite of imposing and that could be part of the joke, that she is the least likely person to be ‘sought after’.

The film’s best character is JRRP’s petrified assistant, Alphonse (Alban Casterman) who looks like an overgrown schoolboy given his first job – he could even have been Brigitte’s son. Constantly ordered about, he has little personality, as he is required to give Sybille a contract and an access code for her script, to prevent the intellectual property from being stolen. (The joke is that no one would steal it.)

Balasko plays Brigitte (surname Ceausescu, after the Romanian former president) as a vain woman whose business negotiation borders on the behaviour of a sexual predator. The meetings are short; she has another film on the go. As her agent says, just because she goes to Cannes, it doesn’t make her a successful producer. She also has ambitions on being an actress.

In the best scene, Brigitte takes Sybille to meet a potential distributor only she is commanded to be quiet as Brigitte sells her film as featuring glamorous women, comedy and action. The distributor sees straight through her. At one point Brigitte and Ingrid have a conversation from their holiday location by skype – Sybille is not allowed to have a holiday herself – and Brigitte returns with a god-awful orange tan from an abused sun bed. In the second best scene, Sybille convinces Julie that she is not right for the film, only to be told by Brigitte not to fire her at all, as the preferred actress is heavily pregnant. Sybille is forced to woo Julie back.

Some of the details are amusing, such as the sign Sybille’s young son makes for his mother’s study to indicate whether she is working or available for interruption. The unconditional devotion to the near absentee mother is touching. The sticking point is that in order to make Sybille’s film special, she must agree not to work for two years.

Arrête ton cinema had an estimated budget of 5.7 million dollars and has only made 1 million dollars at the box office to date. Although it boasts a popular comedy star (Balasko) it has a niche subject. The most popular films by French women directors of the last two years have been comedies, for example Alexandra Leclère’s Le Grand Partage (The Roommates Party), also featuring Josiane Balasko. The film describes how during a cold winter poor people are forced to co-habit in an apartment block with wealthy residents. However, these comedies don’t travel well, if at all – the moderately popular sequel Joséphine s’arrondit directed by Marilou Berry, Balasko’s daughter, hasn’t been released in English speaking territories either.

The dilemma for women directors is whether to appeal to a domestic audience or ‘go international’. In practice, it is dramas or thrillers that translate better, though as Maryland (Disorder) showed they can be completely overlooked in the blink of a short release.

Arrête ton cinema is unlikely to be released in the US or UK, but may do well at festival screenings with sufficiently good advertising. Kurys’ contribution is almost anonymous. There is little to connect this to her 1977 international hit Diablo Menthe (Peppermint Soda) or her 1983 follow-up Coup de Foudre, the latter also known as Entre Nous.

Reviewed at Screen on the Green Islington, North London, Friday 1 July 2016, 20:30 seance, ‘The French Collection’ weekend