According to the ancient Egyptians, the entire universe was made up of masculine and feminine elements, maintained in a state of perfect balance by the goddess Maat. Her numerous fellow deities included a male earth god and female sky goddess. While the green-hued Geb lay back, his star-spangled sister Nut stretched herself high above to form the expanse of sky, hold back the forces of chaos, and give birth to the sun each dawn.

Nut was the mother of twin deities Isis and Osiris. Isis was the active partner to her passive brother Osiris, whom she raised from the dead to conceive their child, Horus. Isis was also regarded as ‘more powerful than a thousand soldiers’. This same blend of nurturer and destroyer was shared with Hathor, goddess of love and beauty, capable of transforming into Sekhmet, a deity so fierce that male pharaohs were said to ‘rage like a Sekhmet’ against enemies in battle.

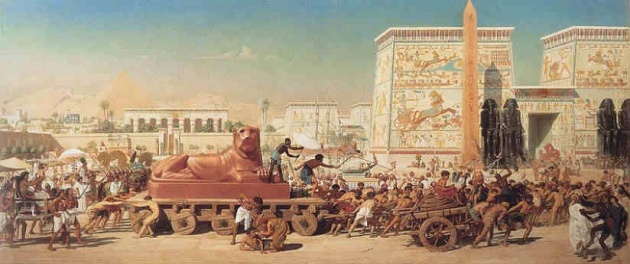

Such mixing of the sexes was not confined to myth, since Egypt’s women were portrayed alongside men at every level of society. This no doubt explains why the Greek historian Herodotus was forced to conclude that the Egyptians “have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind” when visiting Egypt around 450 BC.

So while the most common female title in Egypt’s 3,000-year history was ‘lady of the house’ (housewife), many women worked in the temple hierarchy. Other women were overseers and administrators, or they held titles ranging from doctor, guard and judge to treasurer, vizier (prime minister) and viceroy.

And some women were also monarchs, from the regents who ruled on behalf of underage sons to those who governed in their own right as pharaoh, a term simply meaning ‘the one from the palace’. Yet some Egyptologists still downgrade female rulers by defining them by the relatively modern term ‘queen’, which can simply refer to a woman married to a male king. And while the c15th-century BC Hatshepsut ruled as a pharaoh in her own right, she is still often regarded as the exception that proves the rule – even though the evidence suggests there were at the very least seven female pharaohs, including Nefertiti and the great Cleopatra.

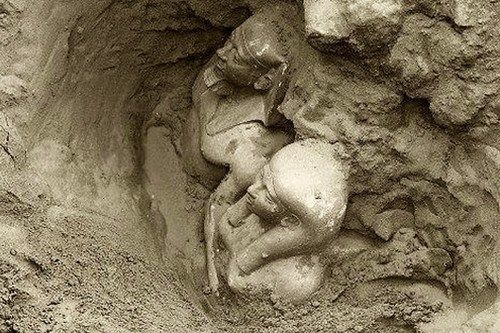

These well-known names were simply drawing on female predecessors dating back to the beginning of Egypt’s written history and the first such ruler, Merneith (whose reign is dated to around 2970 BC). When her tomb was discovered, at Abydos in 1900, it was claimed that “it can hardly be doubted that Merneith was a king”, until the realisation that ‘he’ was a ‘she’ saw her status switched to ‘queen’. Her name nonetheless appeared on a list of Egypt’s earliest kings which was discovered in 1986.

The evidence for female rulers is as fragmentary as it is for many male counterparts – with few known dates of birth or death, and no known portraits for many. Yet, only the women’s titles are routinely downgraded or dismissed, even when the evidence reveals that some, like those profiled on these pages, did rule Egypt as pharaoh.

Khentkawes I (The mother of Egypt):

One woman whose status has long been debated is Khentkawes I. She was the daughter of King Menkaure, and the wife of King Shepseskaf (ruled c2510–2502 BC), and bore at least two further kings – with new evidence supporting the possibility that she herself also ruled Egypt.

Khentkawes I’s funerary complex was as elaborate as the nearby pyramids of her male predecessors – so elaborate, in fact, that her tomb has been dubbed the Fourth Pyramid of Giza. It had its own funerary temple, a causeway and, says Ana Tavares, joint field director of the current excavations at her Giza tomb site, “quite exceptionally, a valley temple and a basin/harbour, which suggests that she reigned as a pharaoh at the end of the fourth dynasty”.

In fact Khentkawes I’s kingly status was suggested as early as 1933 by Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan during his initial excavation of her tomb. For here she was portrayed enthroned, holding a sceptre and wearing both the royal ‘uraeus’ cobra at her brow and tie-on false beard of kingship combined with her traditional female dress.

The tomb also revealed Khentkawes I’s official titles in a hieroglyphic inscription, initially translated as ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt’ until British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner found a “philologically tenable” alternative translation meaning that Khentkawes I had only been ‘the mother of two kings’ rather than a king herself. Yet in light of the new archaeological evidence, her ambiguous title is now interpreted as ‘Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, [holding office as] King of Upper and Lower Egypt’.

Khentkawes I certainly left her mark at Giza, where memories that a female ruler had built a great tomb persisted for two millennia. Yet she was by no means unique, for within a couple of decades her descendant Khentkawes II held the same titles, was again portrayed with the royal cobra at her brow, and had her own pyramid at the new royal cemetery, Abusir. There was even a third such woman whose pyramid complex at Sakkara was so large some Egyptologists have suggested she had ‘an independent reign’ at the death of her husband, King Djedkare, in c2375 BC. But this mystery ruler remains anonymous and forgotten, for not only was her name erased from her tomb complex after her death, the 1950s excavation of her tomb was never published and it remains the Pyramid of the Unknown Queen

Sobeknefru (The crocodile queen):

Despite evidence that some women held kingly powers during the third millennium BC, the first universally accepted female pharaoh is Sobeknefru. Daughter of Amenemhat III, who she succeeded in c1789 BC to rule for approximately four years, Sobeknefru appeared on official king lists for centuries after her death.

The first monarch named after crocodile god Sobek, symbol of pharaonic might, Sobeknefru took the standard five royal names of a king – Merytre Satsekhem-nebettawy Djedetkha Sobekkare Sobeknefru – with the epithet Son of Ra (the sun god) amended to Daughter of Ra. Her portraits blended male and female attributes, the striped royal headcloth and male-style kilt worn over female dress.

Sobeknefru is also depicted in the cloak associated with her coronation. Yet a more complete portrait was identified as Sobeknefru in 1993, and it’s in this that the strong family resemblance to her father, Amenemhat III, can be seen.

menemhat III, can be seen. Sobeknefru created temples at the northern sites Tell Dab’a and Herakleopolis, and also completed her father’s pyramid complex at Hawara. She seems to have built her own pyramid at Mazghuna near Dahshur, but no trace of her burial has been found. If she is mentioned at all in modern histories, it is only to be dismissed as the last resort of an otherwise male dynasty. Yet the throne passed smoothly to a succession of male kings who followed her lead by naming themselves after the crocodile god.

Her innovations inspired the next female pharaoh Hatshepsut (ruled c1479–1458 BC), who adopted the same kingly regalia and false beard. The modern tendency to cast Hatshepsut as a cross-dresser is only possible because her female forerunners have been played down or ignored. Such is the case with Nefertiti. She is judged almost entirely on her beautiful bust, yet evidence suggests she wielded the same kingly powers as her husband and may have succeeded him as sole ruler.

Her example was followed by the 12th-century BC female pharaoh Tawosret, whose titles included Strong Bull and Daughter of Ra. She was the last female pharaoh for almost a thousand years, the final millennium BC being marked by successive foreign invasions of Egypt. The most successful of these were the Macedonian Ptolemies, claiming descent from Alexander the Great and ruling for the last three centuries BC. Their Egyptian advisor Manetho created the system of royal dynasties we still use today. He named five of the female pharaohs, stating that “it was decided that women might hold the kingly office” as early as the second dynasty, in the early third millennium BC.

Arsinoe II (The queen and female king):

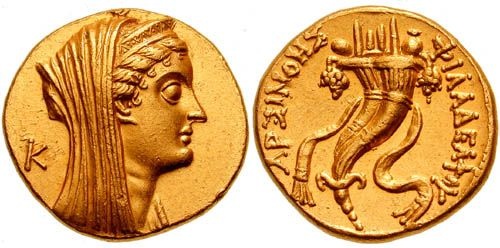

The legacy of Egypt’s female pharaohs certainly inspired Arsinoe II. Married to two successive kings of Macedonia, Arsinoe II then returned to her Egyptian homeland and the court of her younger brother Ptolemy II, marrying him to become queen for a third time. Yet she also became his full co-ruler, with the same combination of names as a traditional pharaoh.

Although these titles were long assumed to have been awarded posthumously, recent research has revealed that Arsinoe II was acknowledged as King of Upper and Lower Egypt during her own lifetime. Like Hatshepsut over a thousand years earlier, Arsinoe became Daughter of Ra and adopted the same distinctive regalia to demonstrate continuity with past practice. Further exploiting Egyptian tradition, Arsinoe was likened to the goddess Isis, twinned with her laid-back brother-husband Osiris. As married siblings, Arsinoe and Ptolemy were equated with classical deities Zeus and Hera for their Greek subjects.

Joint portraits of Arsinoe and Ptolemy highlighted the family resemblance to putative uncle Alexander, whose mummified body, entombed in their royal capital Alexandria, was further evidence of their divinely inspired dynasty.

This too was a relationship Arsinoe exploited to the full, from her subtle adoption of Alexander’s trademark ram’s horns to staring eyes so large some medical historians claim she must have suffered from exophthalmic goitre, a disease that often affects the thyroid. Arsinoe II certainly used her multi-faceted public image to great effect in her political dealings, when she and Ptolemy II became the first of Alexander’s successors to make official contact with Rome in 273 BC.

Then, when Egypt joined Athens and Sparta against Macedonia in the Chremonidean War, Arsinoe’s lead role was acknowledged in an Athenian decree stating that Ptolemy II was “following the policies of his ancestors and his sister”. Athens also honoured the couple with statuary, as did Olympia, where Arsinoe achieved great success in the Olympic Games of 272 BC when her teams won victories in all three chariot races on a single day

Most of Arsinoe’s images were in Egypt, where, according to inscriptions set up in the temple at Mendes, it was decreed that “her statue be set up in all the temples. This pleased their priests for they were aware of her noble attitude toward the gods and of her excellent deeds to the benefit of all people.”

In Egypt’s new capital, Alexandria, Arsinoe’s influence was even stronger. Continuing Ptolemaic tradition by spending vast sums on the Great Library and Museum, she personally financed spectacular public festivals with which to impress her subjects, even if fragments of a lost biography reveal her sneering at the “very dirty get-together” of the crowds as they celebrated in the streets beyond her lavish palace.

Dazzling legacy Having transformed the Ptolemaic house into a dazzling bastion of conspicuous consumption, 48-year-old Arsinoe died in July 268 BC and was cremated in a Macedonianstyle ceremony. Her memory was kept alive at the annual ‘Arsinoeia’ festival, and in the renaming of streets, towns, cities and entire regions in her honour, both in Egypt and around the Mediterranean.

Her spiritual presence was so strong that for the next 22 years of Ptolemy II’s reign, he never remarried and continued to appear with his deceased wife in official portraits, naming her on official documents and issuing her coinage.

As the first Ptolemaic woman to rule as a female king, Arsinoe’s achievements were then replicated by the women of her dynasty, the last of whom was Cleopatra the Great. Cleopatra was the final, and of course most famous, culmination of three millennia of Egypt’s female pharaohs.

Ancient Egypt and It's Female Kings

Posted on at