THE START OF WAR:

On 23 October 1642, at Edgehill in Warwickshire, the armies of King and Parliament came to blows. The road that led them to battle was long, with numerous complex causes. Some claim religious divide was to blame, while others put it down to politics, or regional tensions. Many people believed that it would take just one battle to resolve matters and that, one way or another, the fighting would all be over by Christmas. They were wrong.

When Long Parliament, as it later became known – because it sat for such a long time – assembled at Westminster in November 1640, the members of both houses were almost unanimous in their desire to address what they saw as the abuses of King Charles I’s rule.

Charles had become King in 1625. Believing in his divine right to rule, he felt that Parliament’s job was to vote him money, not discuss his policies. He soon ran into diculties with his early Parliaments, who saw things dierently. In 1629, he dissolved the sitting Parliament and ruled without one for 11 years. This was perfectly legal at the time. However, without a Parliament to vote taxes, Charles was obliged to come up with a variety of ways to raise money. He used outdated laws to fine people, sold monopolies and extended Ship Money, a tax paid by coastal counties, to the whole country. Charles also caused anger over his religious innovations. He supported Archbishop Laud’s emphasis on ceremony in the Church of England, which smacked of a return to Catholicism, much like Bloody Mary in the previous century. Charles managed quite well until his ill-advised attempt to introduce the Anglican forms of worship, particularly the new English prayer book, into staunchly Protestant Scotland. is led to battle and defeat, and Charles was forced to call a Parliament, to vote the money to pay o the Scots.

POWER TO PARLIAMENT:

Led by John Pym, the MP for Tavistock, this new Parliament secured the execution of Straord, Charles’s hated chief minister, and passed an act to ensure that Parliament met every three years and couldn’t be dissolved without its own consent. It also abolished a number of royal courts that Charles had used to impose his will, and declared non-parliamentary taxation, like Ship Money, illegal. Up to this point, Parliament had been united, but then Pym and his circle introduced a bill of controversial reforms to the Church of England. To compound this, he then introduced ‘the Grand Remonstrance’, a bill detailing Charles I’s so-called abuses since 1625.

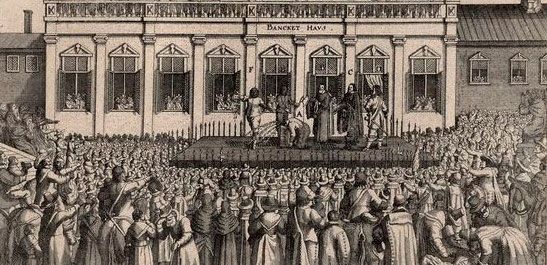

This was too much for some MPs, who began to think that Pym was a greater threat than the King. Charles was gaining support, yet there was still time for one more regal miscalculation. On 4 January 1642, he illegally entered the House of Commons in an unsuccessful attempt to arrest Pym, and four other MPs, for treason.

In the end, the war ultimately began over control of the army. Both King and Parliament agreed that an army had to be raised to suppress a Catholic rebellion in Ireland, but who was to raise it? It was the King’s prerogative to raise an army, but many in Parliament feared that Charles might use his military might against them, too. In the end, both King and Parliament raised troops and England stumbled into war.

THREE WARS, THREE KINGDOMS:

The conflicts that raged across the British Isles in the mid-17th century have popularly been called the English Civil War, but in fact this is extremely misleading. They should really be seen as British conflicts, as few areas of the British Isles were not in some way aected. Many of the events that propelled the nation into civil war took place outside England. Campaigning took place in Scotland as well as England, and both countries invaded each other during the period. What’s more, although fighting in Ireland rumbled on for more than a decade, it’s wrong to see the conflicts as one single war – there were in fact three separate periods of fighting.

FIRST CIVIL WAR (1642-46):

The Royalists are initially successful but, ultimately, Parliament is victorious in England and the King is arrested. The Royalists are also defeated in Scotland. No one can envisage rule without a king, so negotiations take place with the imprisoned Charles over how the country should be governed.

SECOND CIVIL WAR (1648):

Charles escapes, and secretly secures the support of the Scots, who invade England but are defeated. A number of Royalist risings are also suppressed in England. Attitudes harden against Charles for causing yet another war. A minority of Parliamentarians secure his execution in January 1649, and with it the abolition of the monarchy.

THIRD CIVIL WAR (1650-51):

Charles’s son and heir, Charles II, secures Scottish support by agreeing to uphold their form of religion. Despite being defeated at Dunbar in 1650, the Scots again invade England but, in September 1651, in the last battle of the Civil Wars, they are defeated at Worcester. Charles II escapes into exile.

TO BE CONTINUED...

BRITISH CIVIL WAR (17th Century) (Part 1)

Posted on at