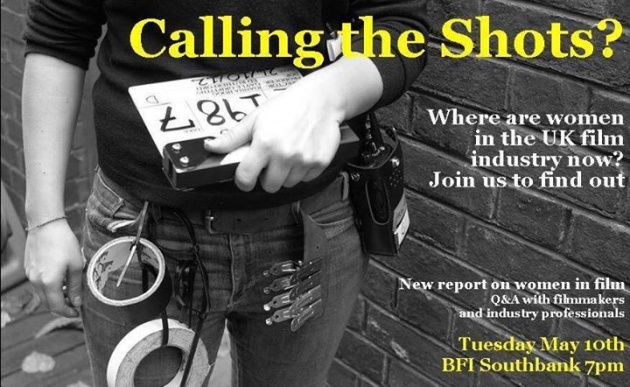

In the effort to see ’52 (new) films directed by women’ within a twelve month period, I have thus far travelled to film festivals in four cities – Vienna, Berlin, Prague and New York – as well as multiple film festivals in London where I live (London Film Festival, Jewish Film Festival, Day for Night Nordic Film Festival, Tongues on Fire and LoCo, London’s Comedy Film Festival). If I waited for them just to show up in my local art house or multiplex, I would be counting a few more grey hairs. Seeing films directed by women takes work. But what about women’s participation in feature film production in the UK?

The University of Southampton, led by Shelley Cobb, Linda Ruth Williams and lead researcher Natalie Wreyford have a £600,000 grant (enough to make two low budget films, at least) to count the numbers of women in six key roles in film production. (Me, I’ve doing my research from my regular salary, less than 5% of that sum.) The roles are: director, writer, producer, executive producer, cinematographer and editor. The results for 2015, their baseline year, are not encouraging. Only 13% of films in production classed as British (these include co-productions) have a woman director. This amounts to 28 films. Four of these had a male co-director. Seven of the 24 were documentaries. Their research looks at the number of films directed by women that have a woman producer and a woman editor. The consensus was that women hire women.

The number of women minorities helming feature films in the UK in 2015 is four.

Missing from their analysis, but essential for an understanding of the problem, is a statement of how many of these films have found distribution. If I had seen the 24 British films referenced here, I probably wouldn’t need my passport. They are not getting into cinemas.

Missing also from their work are the budgets that women directors command in relation to men, the types of films that get made (comedy, drama, period, romance or all of the above) and the audiences that they attract.

Missing too is work on the longevity of women’s careers in feature film production. I would direct the researchers to the example of Lezli-An Barrett, who has but on feature to her name (Business as Usual, 1987).

So what is the problem?

The panel considered the Swedish 50/50 model. The Swedes made a decision to give 50% of production grants to women directors and 50% to men. The result was that when it came to an awards ceremony, 69% of the winners were films directed by women. Once a level playing field is established, women have proven that they can excel, at least on the basis of one year’s results. Three of the films in my study (at time of writing) are from Sweden: My Skinny Sister, A Serious Game and Granny’s Dancing on the Table. Australia and Canada are considering following suit.

But here’s the problem. The British Film Institute is not the principal funder of movies in the UK. The BBC and Channel Four (followed, I suspect by Universal Pictures and Studio Canal in conjunction with the production company Working Title) are. So only an industry code of conduct – with major producers signing up to it - could offer such a mandate. Could such a code of conduct be negotiated? The film industry is still an industry, financing work that has a reasonable chance (on paper) to recoup production funds. So women have to make films that general audiences want to see. There is ample evidence (in the US, at least) that they can do so, with the box office success of directors like Penny Marshall, Amy Heckerling, Catherine Hardwicke and Kathryn Bigalow. Their films though are to some extent gender neutral – that is, many of them could have been directed by a man of equal talent and turn out broadly the same – male directors took over the Twilight franchise established by Hardwicke. In my observation, it is the films at the sub-blockbuster level directed by women that are the most interesting. Also, there is no equal level of talent, except for functional craftspeople. In an artistic profession, uniqueness should be felt.

There is also a mindset to overcome: when a male director fails, and most of them do, they fail for themselves. When a woman director fails (same for minorities) they fail for women everywhere. The number of women who get to make a second or third feature drops off significantly. In my study, more generally, I have seen women with twenty year career breaks - for example, Gilliam Armstrong - who don’t have Terrence Malick’s disdain for the industry. (Or maybe they do.)

There could be more women in television, a feeder to the film industry. There were complaints that no woman has ever directed an episode of Doctor Who – ‘it’s genre, the BBC’s flagship show’. I would like to nominate Lexi Alexander, who directs episodes of Supergirl. Only one episode of Sherlock had a woman director (Rachel Talalay). Leading TV producer Beryl Vertue has never hired a woman director.

Producers and financiers still ask women directors about their child care arrangements, whether these are in place before they start work. Men are not asked that same question.

Women have to endure sexism at work and distrust. Even crews do not mix well; male crews have lockers, women are expected to sit behind a desk.

Critics should take women’s films more seriously and – this from the founder of the Bechdel Test Festival – there should be more women film critics. (Comment: there are more than the 20% than she suggests, and a woman, Terri White, edits Empire, the UK’s leading film magazine; the US doesn’t even have a leading film magazine anymore, with Premiere having ceased publication in the 1990s.)

On Saturday 14 May in Cannes, Amanda Nevill of the British Film Institute is giving her response as to what the BFI can do to remedy the situation. Would it have been better to have the discussion on the counting project after her report? Perhaps, especially as the dialogue got more heated as the evening went on. (‘50/50 by 2020 was one slogan chanted.) There are other things that could be done, including voluntary mentoring programmes, though training isn’t everything.

Having studied Film and Drama at a leading Southern England University, I recalled my class of 1994. An equal number of male and female students, yet women gravitated more towards theatre and men more towards film. Perhaps this was to do with the way the subject was taught – more women playwrights like Caryl Churchill and Timberlake Wertenbaker, few films by women directors and a focus on the western, kitchen sink British cinema and Luis Buñuel. So there is a role for education too.

The panel included: Lizzie Francke, Senior Production Executive at the British Film Institute; Kate Kinninmont, Chief Executive of Women in Film and TV (UK); Corrina Antrobus, founder and director of the Bechdel Test Festival; Hope Dickson Leach, filmmaker; Gurinder Chadha, film director

I know I have missed one of the panellists out (Sarah) - apologies. With thanks also the photographers at the event