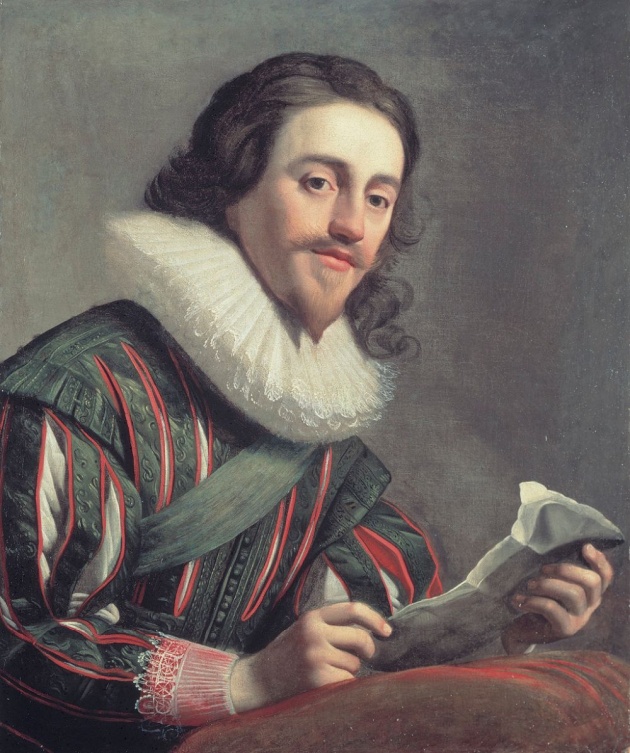

Charles I took his kingship seriously. A fervent believer in the divine right of the monarchy, he thought he was subject to no earthly authority. As he saw it, his right to rule came directly from on high, and so he was answerable to God alone. Yet when he was born in 1600, nobody had expected him to become King. His parents, James I and VI and Anne of Denmark, had an older son, Henry. However, when this first-born died in 1612, the young Charles found himself heir to the thrones of England (which at the time included Wales), Scotland and Ireland. He was thrown into a rigorous training regime to prepare for the crown. Charles was short, aicted with a stutter and had weak ankles, possibly caused by rickets. Hardly the image of a powerful ruler. However, things soon turned around – he had always been an able student but, as he reached maturity, he also became a skilled horseman and marksman, conquering his disabilities with the same dogged determination that would later be his undoing.

Parliament and its forces may have defeated King Charles I in 1646, but they still had the problem of deciding what to do with him. At that time, few people would have considered the possibility of deposing their King, let alone executing him, so some form of agreement was called for. But Parliament was divided. e majority, known as Presbyterians, loosely allied with the Scots, favoured a negotiated settlement and the disbandment of the New Model Army. However, a significant minority, known as Independents, had links with the army and wanted to take a harder line. Even so, all of Charles’s opponents accepted that while he had been wrong, he should still have at least some limited powers as King.

The monarch had ended the war as a prisoner of the Scots. They later handed him over to Parliament who kept him under house arrest at Holdenby House in the Midlands. The leaders of the New Model Army – who were worried they might be excluded from any deal made with the King by the Presbyterian majority – seized Charles I on 4 June 1647, eventually holding him at Hampton Court Palace. Charles lived there in comfort, saw his children and was visited by representatives of both Parliament and the army, neither of which had given up hope of reaching some form of compromise.

While these discussions were taking place at Hampton Court, meetings of a diserent sort were taking place downstream at Putney. Ocers and men of the victorious New Model Army were debating the very basis of political society, including the agenda of the ‘Levellers’. is was a movement that argued for, amongst other things, greater religious toleration, an extension of the franchise to allow more men to vote and curbs on the power of the monarchy. It was a sign of the times.

HEAD OF PROPOSALS:

In November 1647, Charles escaped from Hampton Court and made his way to the Isle of Wight, where he hoped the island’s governor, Colonel Robert Hammond, would help him. But the King and his advisers had misjudged Hammond, who refused to betray the Parliamentarian powers and Charles found himself a prisoner again, this time in Carisbrooke Castle. ere, he continued to meet with representatives of Parliament and the army. at summer, the army leadership had presented Charles with a settlement plan called the ‘Heads of the Proposals’. is would have allowed Charles to control the army and appoint his own advisers after ten years. It also permitted the survival of bishops and the prayer book for those who wanted it. In exchange it called for biennial Parliaments and freedom of worship for independent congregations outside the established church.

A more flexible king might have accepted these remarkably generous terms, but not Charles I. While talking with Parliament and the army, he had also been secretly negotiating with the representatives of his other subjects, the Scots. Together, they agreed a plan known as the ‘Engagement’. In return for the temporary adoption of Presbyterianism in England, the Scots would invade the country and restore Charles I to power. e invasion would be supported by risings in both England and Ireland. e result was the Second Civil War. It was a worrying time for the English Parliament, but its forces were up to the job. They suppressed the Royalist risings, and defeated the Scots at Preston.

e second war led to a hardening of attitudes among the army and the Independents in Parliament. As they saw it, God had judged Parliament right, by handing them victory in the First Civil War. By causing a second conflict, Charles had defied God’s judgement and had caused unnecessary bloodshed. Charles would have to pay for his actions, but how? The Independents did not command a majority in Parliament, where the Presbyterians were still in favour of negotiating with the King. On 6 December 1648, the New Model Army took action. In what became known as ‘Pride’s Purge’, a force of soldiers under Colonel Thomas Pride took up position at the entrance to the House of Commons and waited for the MPs to arrive for the day’s sitting. Pride arrested 45, who were deemed to be enemies of the army, and had them locked up in places across Westminster. More than 180 more were refused entry and wandered away, no doubt thinking that the army they had brought into being had become a far greater threat than the King had ever been. Others left in protest. Two- thirds of the Commons’ membership had been purged and the remainder, barely 200 members, became known as the ‘Rump’ Parliament.

CHARLES I (The King Who Got Executed By His Own Parliament) (Part 1)

Posted on at