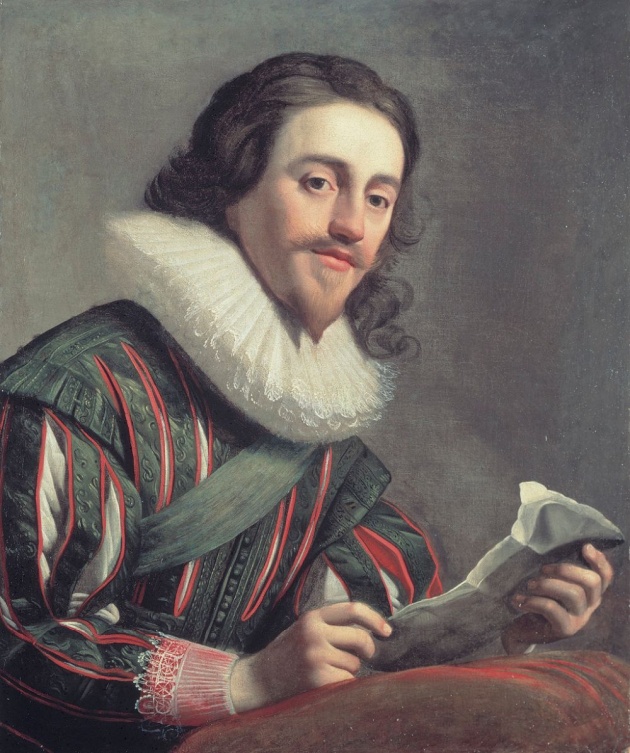

THE KING’S COURT:

On 13 December, the Rump broke o negotiations with the King and brought him to Hurst Castle, a grim fortress perched on a shingle spit in the Solent, and then onto Windsor. Cromwell attempted to act as mediator, initially hoping Charles could be persuaded to abdicate. But it soon became clear that the King would never contemplate it and Cromwell joined those who sought the King’s trial and, eventually, his execution. On 6 January 1649, the Rump established a High Court of Justice to try Charles I, and named 159 commissioners to serve on it. Over half of those named would never attend. e House of Lords refused to pass the bill establishing the Court and, needless to say, it never received the royal assent that was technically required. The Rump pressed on, regardless.

On 10 January, the highest-ranking judge they could find who was prepared to preside over the trial, an obscure Cheshire lawyer called John Bradshaw, was appointed Lord President of the Court - and given a bullet-proof hat for protection. On 19 January, the day before the trial, Charles was brought from Windsor to St James’s Palace, where he would spend the last 11 nights of his life. e following day, dressed in black, carrying a cane and wearing the star of the Order of the Garter, he walked to face his judges in Westminster Hall.

The trial was not without its moments of drama. As the register of commissioners was read out and it came to the name of omas Fairfax, Commander-in-Chief of the army, a masked woman stood up in the public gallery. “He has more sense than to be here”, she shouted. It was Fairfax’s wife, Anne. After the proceedings were declared open, John Cook, the Solicitor General, introduced the charges against the King. He’d only just begun when Charles tried to interrupt him, tapping him on the shoulder with his cane and telling him to “hold”. Cook ignored this and carried on with the indictment so Charles rose from the red velvet chair he was sitting in and, as he poked Cook again, the ornate silver end of his cane broke o and clattered onto the floor. ere was a pause as Charles waited for someone to rush forward and pick it up for him. is would have happened in the past - but not now. Nobody moved and Charles bent down and picked it up himself.

Andrew Broughton, one of the two Clerks of the Court, read the full indictment. It said that “out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will,” Charles had “traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament and the people therein represented”. It then went on to list the battles at which Charles had been present together with the events of the Second Civil War. It concluded that because he had caused the wars, he was guilty of all the “treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs” committed in them.

amages and mischiefs” committed in them. What happened next has been described as Charles’s finest hour. When given the opportunity to speak he refused to enter a plea, demanding instead, with no trace of his stutter, to know by what authority they sought to try their lawful King. He maintained that the House of Commons on its own could not try anybody, or have the authority to establish a court. He argued that the injustice he was suering was what all his subjects would suer at the hands of what he dismissively called this “fraction of a Parliament”.

Charles appeared before the court four times in all, and each time he challenged its authority and refused to enter a plea. e Rump and the army’s desire for an open trial that vindicated their actions had backfired badly. When Charles repeatedly demanded the right to a trial by a properly constituted court acting on the basis of established law, they simply had no answer.

Nevertheless the show had to go on, and the court proceeded as if the King had pleaded guilty (this was standard legal practice in the event of a refusal to plead).

vent of a refusal to plead). Witnesses were heard, though Charles was not present to hear or question them, and on 27 January the judgement was reached that “Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy to the good people of this nation shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his body”. The Commissioners who were present rose to their feet to show their agreement with the sentences and over the next two days, 59 of them signed Charles’s death warrant. Cromwell was third to sign, and he is said to have relieved the tension by flicking ink at Henry Marten, one of his fellow judges. On 30 January 1649, King Charles I was beheaded outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall. In March, the Rump passed Acts abolishing the monarchy and the House of Lords. England was now a Republic.

CHARLES I (The King Who Got Executed By His Own Parliament) (Part 2)

Posted on at