When the Japanese government announced its intentions to purchase the privately owned islands, the Chinese saw the move as a threat to their national interests. The Japanese government claims that buying the islands was important in order to prevent them from being acquired by the Japanese right-wing politician, Shintaro Ishihara. According to Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, the islands were merely passed from one Japanese party to another, and therefore, it would be unnecessary for China to react so aggressively. However, the Chinese remain extremely cautious and suspect that the Japanese are using that as an excuse to fortify claims over the islands.

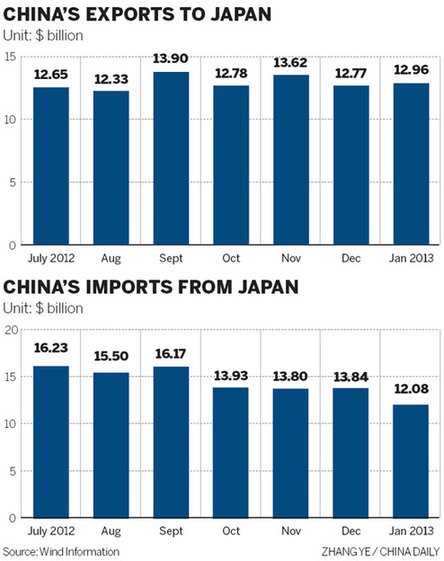

Trade between China and Japan has no doubt suffered as a result of this conflict. Japan’s economy, in particular has been impacted significantly, more so than China’s. While both countries depend on each other, Kazuo Yukawa, a professor at Asia University in Tokyo, states that “China and Japan need each other, but honestly speaking, Japan needs China more. So Japanese feel torn. They want to defend their territory, but few would say to do so at the expense of business.” Japan has already witnessed a 10.3 percent decrease in exports – in September, many Chinese consumers began boycotting Japanese goods, including Japanese technology and automobiles. Sales for Toyota cars in China have been cut in half just in the month of September. Anti-Japanese sentiments are so strong that the Japanese are beginning to question the sense in trying so desperately to assert their control over the islands when there are much larger risks at stake. Japan’s economy has already been steadily shrinking after the earthquake and tsunami devastated the nation. In fact, it is likely that Japan will face a recession by the end of the year. If Japan is unable to at least somewhat settle its disputes with China, recovery will take even longer than anticipated.

The U.S. has also unsurprisingly become involved in the situation. The Chinese are growing increasingly distrustful of they believe the U.S. and Japan are plotting. Retired Chinese diplomat Chen Jian “accused the United States of encouraging the right wing in Japan, and fanning a rise of militarism” (Perlez A3). In response, the U.S. stated that it would support Japanese defense of the islands, as promised in a mutual defense treaty it has with Japan. The U.S. cooperated with Japan in carrying out an operation known as Keen Sword, which intended to “simulate the re-taking of an island from an enemy force” (Mcdonald 1). Neither the Diaoyu Islands nor the location of the military exercise was specifically mentioned, but it was apparent that it would take place near the disputed islands. The timing of Keen Sword has aroused suspicion, but military officials insist that the operation is a routinely act that has been scheduled and carried out every so often.

_fa_rszd.jpg)

Recently Japanese defense minister Satoshi Morimoto has sought discussions with the U.S. about revising their security alliance. Japan’s increased concern over maritime altercations with China has prompted the nation to set up military agreements with the U.S. in the event of a serious confrontation. The Chinese have persisted in sending surveillance ships in waters within close proximity to the islands, which has aggravated the Japanese. Morimoto did not disclose what he intends to specifically change in the agreement, but it is inevitable that it will concern policies governing China’s maritime activities. Guidelines between the U.S. and Japan were last updated in 1997 over North Korea’s nuclear program. Concerning the islands, the U.S. has taken up a somewhat neutral stance, but showing some favoritism towards the Japanese. The Japanese, however, are hoping that the U.S. will eventually announce its full-fledged support for Japan. Still, many Japanese are skeptical that the U.S. “would actually risk a war with China over what are essentially barren rocks surrounded by shark-infested waters” (Fackler A5). China, on the other hand, does not believe Washington has been neutral or fair in its attempts to appease both nations. When the U.S. gave the islands back to Japan in 1972 without first consulting China, the Chinese interpreted this as a sign of American partiality towards the Japanese. Commentaries in the People’s Daily newspaper have warned, “It’s wrong and risky to continue playing with the Diaoyu Islands by naively relying on strengthening its military alliance with the United States.”_fa_rszd.jpg)

As of now, the future between China and Japan looks grim. While the islands may appear to be an insignificant source of conflict, they represent the long-standing damaged relations between the two nations. Past issues were never truly resolved, and the slightest provocation was all it took to spark suppressed hostility. History often plays a prominent, if not direct, role in dictating the relations among nations. In the case of China and Japan, neither nation will be willing to compromise until the roots of their problems are resolved. The disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are essentially indications of the actual fragility that has long existed between both nations. It will take time and effort from both parties to resolve past issues before current and future relations can be reestablished.

_fa_rszd.jpg)