Over the decades during which I have worked in and written about Pakistan, there have been so many supposed national "turning points" at which the country failed to turn that I have almost ceased to notice them.

But when earlier this year the Pakistani Government described China's planned energy and transport corridor through Pakistan to the Arabian Sea as a "fate changer", it may - perhaps - have been telling the truth.

At more than $46bn, the planned Chinese investment in this project is some four and a half times the total US economic aid to Pakistan since 9/11 (though admittedly largely in the form of low-interest loans).

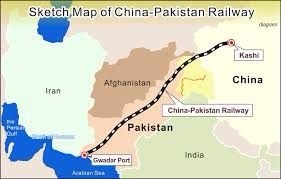

Counting the cost - The China-Pakistan economic corridor

Apart from energy pipelines and road-and-rail links between western China and the Pakistani port of Gwadar, the plans include massive investments in Pakistan's own energy, transport and telecommunications infrastructure, including what would be the world's largest solar power generating complex at Bahawalpur.

Pakistani dream

These projects, if realised - and this is a very big if - have the potential to bring in tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars in additional investments. They could restore Pakistan's economic growth of the early 1960s, which led economists at the time to predict that the country would be one of the future leading economic powers of Asia.

This dream was lost when Pakistan recklessly attacked India over the Kashmir dispute in 1965, and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto subsequently abandoned free market policies in favour of a horribly corrupt and badly managed populism.

China's commitment to the core energy and transport aspects of the plans does not seem in much doubt. This corridor will be a key part of Beijing's "One Belt, One Road" strategy, intended to link China by land with Europe, Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

[W]hile Beijing certainly regards Pakistan as a potential strategic ally against India, it has also brought strong influence to bear on Pakistan not to back attacks against India, and to seek a reduction of tension with Delhi.

This strategy is driven both by economic interests and security concerns. China depends on imports for 60 percent of its oil, and the great majority of this is carried by tanker across the Indian Ocean and through the Strait of Malacca.

Beijing sees this as rendering China dangerously vulnerable to pressure from India and the US, as well as to attacks from fighters.

Improving security

Security obstacles in Pakistan have greatly diminished in recent years thanks to the successful offensives of the Pakistani army against the Pakistani Taliban rebels. These offensives were supported - at last - by a united Pakistani public opinion.

The separatist rebellion in Balochistan - where the port of Gwadar is situated - remains a threat, but so far its military capacity has been very limited. It would only increase radically if India decided to increase its support for the rebels via Afghanistan with the deliberate aim of blocking the Chinese corridor.

Apart from being extremely dangerous and irresponsible in itself, such an Indian strategy would lead to a breakdown in both diplomatic relations and trade with China. That would be a very unwelcome development as both the Indian National Congress and current Bharatiya Janata Party governments in recent years have tried to improve these relations.

Fears have been expressed in India about the ways in which this new Chinese corridor would both strengthen Pakistan and increase China's geopolitical and economic influence in the region.