Deep beneath the Egyptian desert on 26 November 1922, British Egyptologist Howard Carter stood nervously before a sealed doorway. Waiting anxiously in the relative coolness of the dark, recently excavated corridor behind him were his patron, Lord Carnarvon, close friend Arthur Callender and Lady Evelyn Herbert, Carnarvon’s daughter. Above them, the barren sands of Egypt’s mysterious Valley of the Kings swirled under the relentless heat of the Sun.

The group knew it was standing inside the tomb of the 18th Dynasty king Tutankhamun - seal impressions on the tomb’s now dismantled outer door attested to that. But the outer door also showed signs that it had been opened before, on more than one occasion. Would the pharaoh’s tomb be intact, or had it been pillaged by grave robbers, its priceless contents gone forever?

Using his chisel, Carter made a small breach in the top left-hand corner of the doorway. Once the presence of oxygen had been determined, the hole was widened and Carter peeped through, aided by the light of a candle. “It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker”, wrote Carter in his journal a while later, “but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another. ere was naturally a short suspense for those present who could not see, when Lord Carnarvon said to me 'Can you see anything'. I replied to him 'Yes, it is wonderful'.”

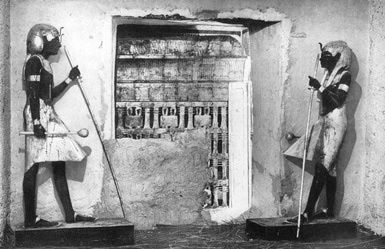

What Carter beheld was indeed wonderful. His journal describes a collection of treasures that included “two strange ebony-black effigies of a king, gold sandalled, bearing staff and mace”, gold furniture, flowers, ornamental caskets and “a confusion of overturned parts of chariots glinting with gold”. But the most significant discovery was a sealed doorway, set between two sentinel statues – perhaps the final resting place of the young pharaoh himself.

JOURNEY TO DISCOVERY

Carter’s uncovering of Tutankhamun’s tomb was the culmination of years of hard work, disappointment and sacrifice. In 1907, after a number of years working on excavations at ebes, as well as a period as chief inspector of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, Carter was employed by enthusiastic amateur Egyptologist Lord Carnarvon, but their work in the Valley of the Kings did not begin until 1915. Although it was widely believed in archaeological circles that the area had already yielded all the tombs that were to be found there, Carter remained convinced that Tutankhamun’s tomb lay beneath the sand.

The burial site of the pharaoh was the holy grail of Egyptology. King of Egypt for just nine years, Tutankhamun probably inherited the throne at the age of eight or nine and quickly set about restoring the old gods of Egypt that his father, Akhenaten, had replaced with the solar deity Aten. That Tutankhamun had died young was not known by the archaeologists searching for him, though; it was assumed he had died a natural death as an old man.

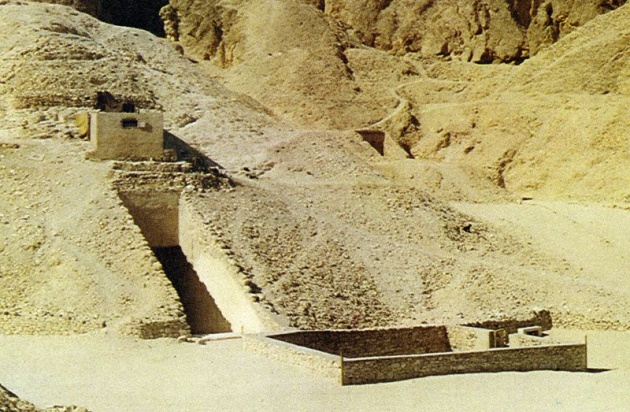

For seven years, Carter and his team searched for the tomb, resuming their work with even greater intensity in 1917 after the three-year break caused by World War I. But, by 1922, Carter’s wealthy benefactor had lost patience with the lack of results, and Carter and his team were given one last season of funding in which to locate the tomb. It was make or break for the young archaeologist. On 4 November 1922, the first hints of the tomb’s entrance were found, located beneath the remains of workmen’s huts built during Egypt’s Ramesside Period of c1292-1069 BC (named after the 11 pharaohs who took the name of Ramesses). The entrance comprised a sunken staircase of some 16 steps, located about four metres below the entrance to the nearby tomb of Ramesses VI. “It was a thrilling moment for an excavator... to suddenly find himself, after so many years of toilsome work, on the verge of what looked like a magnificent discovery – an untouched tomb”, wrote Carter in his diary for 5 November 1922. An encrypted telegram was immediately sent to Lord Carnarvon and preparations began in earnest for the opening of the tomb.

ENTERING THE TOMB

The sealed doorway through which Carter had viewed so many Ancient Egyptian treasures, was opened on 27 November, some three weeks after the initial discovery of the tomb’s entrance. As the group entered the room – later known as the Antechamber – illuminated by an electric light rigged up for the occasion, they were confronted by what Carter described as “a heterogeneous mass of material crowded into the chamber without particular order, so crowded that you were obliged to move with anxious caution, for time had wrought certain havoc with many of the objects...” Many of the items were overturned, or had been broken, presumably by an early intruder, but the quality, richness and number of the pieces within was undeniable. Beneath a gilded couch in the south-west corner of the room another sealed doorway was discovered, “broken open as by some predatory hand”. Crawling underneath the couch and peering through the opening, Carter and Carnarvon saw yet another chamber (later named the Annexe) full of furniture, statuettes, alabaster and faience vases, again in a state of chaos that suggested a would-be thief hunting for valuables. But as well as their plethora of objects, both chambers were also notable in another sense: their lack of mummy or mummies. is could mean only one thing – that the group was standing in the anterior portion of the tomb. e tomb chamber of Tutankhamun must lay beyond a sealed doorway, located between two guardian statues first spotted through the initial breach in the doorway the previous day.

TO BE CONTINUED...