Modern technology - there is a time delay and an echo. Michael Moore (celebrated documentarian and liberal advocate) is asking us: ‘so where is this in London? Happy?’

No, we were not in HAPPY, TEXAS (I have a good memory of that film – starred Steve Zahn and Jeremy Northam). We are in the London Borough of Hackney, specifically the Hackney Picturehouse. It’s Friday night, ten past eight, and most of the cinema-going public is watching GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY in the larger ‘Screen One’. (I could hear it through the walls of the lavatory, doesn’t loosen the stool I can tell you.) We are in Screen Three. There is a laptop in front of us and an image of our audience, supposedly forty of us but it feels a lot less is being beamed to a movie theatre in Traverse City in Michigan, USA. There on stage is the shambling form of Michael Moore, wearing a Film Festival baseball cap, clearly worried about sunstroke in a movie theatre. No wonder he doesn’t get out much.

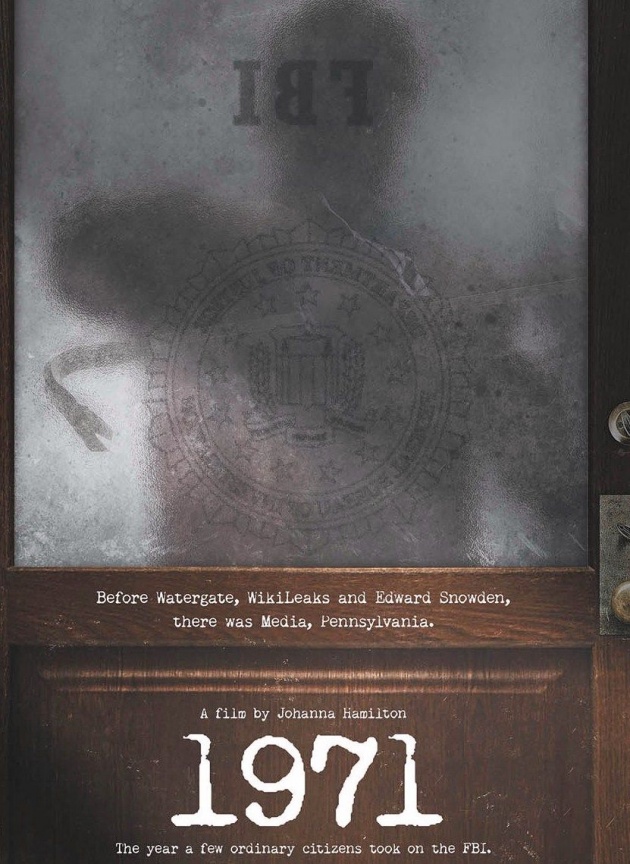

What are we doing there? Well, as a last minute addition to the Traverse City Film Festival, British director Johanna Hamilton’s documentary 1971 is being screened to cinemas around the world simultaneously. The venues are eclectic to say the least. Quite apart from Hackney, where the turnout is disappointingly low – who doesn’t want to debate freedom of information on a Friday night, evidently plenty – there is a nice looking theatre in Bergen, Norway (good turn-out). Then there is someone’s front room in Davian City, China. Four young people – boy, boy, girl, boy - are sitting on a sofa with names above their heads. They don’t look like a ‘Leo, Max, Dream and Jerry’ but you can understand wanting to give yourself a false name to engage in discourse on the internet. It is 3:00 am in China and this crowd is dedicated – not an energy supplement or cup of coffee in sight. Move over to Australia, and there two venues, another front room in Runaway Bay filled with older people in hippy outfits (one of them has a dog; ‘there are no subtitles for the dog’, Mike informs them) and the Sun Theatre in Yarraville. I don’t know where either of these places is, but I can tell you the crowds look spritely for five in the morning.

So, very eclectic crowd – there are two friends of Johanna in our audience. We look at the screen, divided into nine. It’s like watching CELEBRITY SQUARES. We are top-left. Davian City is bottom-left, , the Willie Rushden square for those who remember the British version. Michael Moore is in the middle, Bergen is bottom-right. Yarraville top-right and Runaway Bay (backs to us mostly) top-middle.

So what is 1971 about? It is the story of the break-in to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) offices in Media, Pittsburgh by the Citizen’s Commission to Investigate the FBI. No, I haven’t heard of them either. The perpetrators who on March 8 1971 (the night of the Ali-Frazier fight, Ali promising to crawl on the floor below Frazier and proclaim him the champion if he was defeated) stole 10,000 documents and sent them to three newspapers – the Washington Post, New York Times and Los Angeles Times. Only the Post ran them, for reasons only explained in the Q and A (the others weren’t received by the addressees but turned over to the FBI). The thieves were never caught. Nor did they receive any kind of pardon. They are still fugitives from justice, destined to take their secret to the grave. Except that many of them gave testimony to Betty Medsger, the Washington Post reporter who received and subsequently arranged for the publication of the material and much later (early in 2014), sensing parallels between what they did and what Edward Snowdon has done, published a book. They were also interviewed on camera by Hamilton. I guess they were too old to be worried about jail time, though in practice were excused with the promise that the Bureau would take no retrospective action (‘we’re a different organisation now’). For the record, participants in the film are only referred to by their first name, John, Bonnie, Bob, Keith and so on.

What were they doing? Back in 1971, people were still protesting against the Vietnam War. They were appalled by the treatment of college students in Jackson State who were mowed down by the police. (‘All I could hear was machine gun fire,’ noted Keith, the locksmith of the operation.) Groups moved from non-violent resistance to non-violent disruption. The intention of the Commission, who did not have a name at that point, was to emulate the draft office vandals who broke into army recruiting offices and burnt records to prevent young men being called up. They wanted to target the FBI, to take away their anti-protest intelligence. What they discovered after stealing said documents shocked and appalled them – an orchestrated attack on the New Left, COINTELPRO, to give all dissenters the impression that they were being followed. Not that the group had time to read all the papers – they had to get rid of the evidence fast. Others, notably the Church Commission, who held hearings in 1975 to investigate the FBI in the wake of the Watergate Hotel break-in, did that.

How easy was it to break into an FBI office? (And I don’t advocate this, by the way.) Well, you don’t go for the big ones. Fortunately, at that time the FBI had 500 field offices whose location you could look up in the phone book. There was one in Media, Pittsburgh that fit the bill.

First, you case the exterior to check how well the building is guarded – the FBI rented office space and didn’t own the whole spot. Then you send someone in under cover to check out the interior. Tying her hair above her head and putting on glasses, Bonnie Raines, the wife of one of the group, who wanted to do more for the operation than serve spaghetti and meatballs, masqueraded as a woman who wanted to enquire about employment opportunities. As the field officer condescended to her – the FBI is a great place to work and, who knows, you might get to stop the lambs bleating at night (worked for Clarice Starling) – Bonnie drew the layout of the office, focussing with difficulty through prescription glasses that she didn’t need.

Why 8 March, 1971? If you are going to commit a major crime, you do it when there is a maximum distraction. So if you are a male guard protecting an important building, you are gonna be watching the Ali-Frazier fight. You’ve gotta see it to pronounce in the bar afterwards. Of course, Ali famously refused to fight in Vietnam, so you imagined ‘the Man’ (authority) would be backing Frazier – who is Cassius Clay to opt out of fighting for his country?

There was a problem with the lock, but the group did it, dispersed the documents, saw their publication by the Washington Post and waited anxiously for a knock on the door. What these 10,000 documents revealed was a comprehensive surveillance programme, both real and suggested, to instil paranoia and submission even amongst groups in the Women’s Liberation movement, who did not have a track record in destructive subversion. If people thought they were being watched, they wouldn’t act.

Why didn’t the Citizen’s Commission get caught? Every successful enterprise deserves a sequel. GODFATHER PART II, THE FRENCH CONNECTION II, THE EXORCIST PART II, then there was the activities of the Camden 28. They attempted another break in – and got caught. The police thought by catching the Camden group they had within them the perpetrators of the earlier break in. The investigating FBI agent wasn’t entirely convinced but in 1975 the case was closed.

What about Number Nine? There was a ninth member of the Citizen’s Commission who dropped out. His identity is secret to this day. (Medsger and Hamilton know his name, but nothing else.) Number Nine threatened to turn the group in, but didn’t do so. Records later showed that after the break-in, of all the members of the group Number Nine was the one under 24 hour surveillance.

What about those contemporary parallels? It is easy to see that the Citizen’s Commission were the forerunners of Julian Assange and Edward Snowdon, putting documents in the public domain that described the heinous acts that the US and other governments were doing in the name of their electorates. Governments regard these acts as treasonable, against the national interest; only an elected government has the authority to define what that means – that is the gift of democracy, the electorate has a responsibility to ensure the authority is properly conferred. (That’s why we vote.) Back in 1971, large sections of the population could see what the government was doing overseas was wrong and did not have the luxury of an imminent election to stop it. Today, there do appear to be threats to national security from dissident groups who are either from overseas or opt out of the democratic process at home. What do you do about them?

Can you justify mass surveillance programmes? There is a liberal response that argues that a system that can spy on everyone to protect the majority from a minority is wrong. People have a right to privacy. There is another response. People have an obligation to conduct themselves well, so that in the majority of social transactions, there is no secret to be unearthed. Of course, information can be misused to deny you a job, health insurance, a mortgage. Statistical data can identify you as a risk. The answer then would be to prevent those who would act in a discriminatory manner for commercial reasons – and it is all about the money - to be denied access to that information. If whistleblowers – and individuals acting in self-interest – disclose that information, what can you do about that? That is why Snowdon and Assange attract an ambivalent response. Who are they? What is their self-interest? What protects us from the information they steal being passed on to others? You can sue a government, but not obtain justice from an individual claiming political asylum.

Today people arguing against mass surveillance programmes are really anticipating problems down the track. They need reassurance and responsible government. There aren’t mass protests yet because people haven’t felt the effects of invasion of privacy. And they haven’t an alternative answer to the question: how do you identify people who mean you harm?

Nevertheless, it was good to see Michael Moore again. I miss his agit-prop stunt documentaries and righteous anger directed at deserving targets. What has he got in store? Apparently he has been plotting with another film director to transport Edward Snowdon from Moscow to Bolivia. Snowdon’s asylum in Russia runs out next month (September 2014) and he is in danger of being extradited. The moment he enters international air space, he’ll be arrested for treason to face the same fate as Bradley Chelsea Manning, the leaker who supplied Julian Assange with documents about American activities in Iraq, and the killing of innocents. Is this a ruse or a decoy? Moore is something of a tease so you can’t tell whether it is the conversation of two Soviet filmmakers in the early 1920s planning their next film without access to celluloid.

Screened Friday 1 August 2014, Hackney Picturehouse, East London