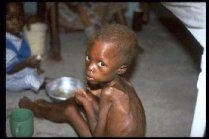

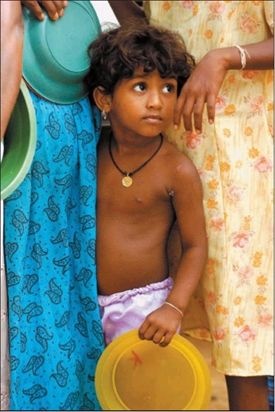

I often find myself wondering what people, people in the street, western people in general, my readers perhaps, think when they see something like the recent Unicef report, which states that child poverty in developed nations has risen significantly.

How many of you who live in Europe still see the EU as something good and beneficial when you see that not only does Greece today has 25% unemployment and 55% youth unemployment, and its child poverty rate also went up from 23% to 40.5% since 2008? Or do you put the blame not with the EU, but elsewhere?

It’s not just those numbers, I wonder to what extent you Europeans think the numbers are about yourselves, to what extent you feel responsible, what they do about it. Same for Americans, who live in a country where 1 in 3 children grow up in poverty. How much of that do you think has to do with you? What would you say you can or cannot do to make those numbers better, and what do you actually try to do?

Do you even think less child poverty is better for society, and for yourself, or that less unemployment is a good thing, or do you see that as perhaps for instance the proper way to generate growth in an economy, Darwin-style? Lots of people seem to think that way, so at least you wouldn’t have to feel alone.

Obviously, the UnIcef report should be linked to recent reports that state the number of billionaires in the world has doubled in the same time slot, the past 5-6 years. One can’t very well argue that these things have nothing to do with each other. What the two combined say is that our societies are changing in very fundamental ways.

And at some point you need to ask yourself what you think about that. And if you find this a negative development, what you can do to correct it, as well as what you are in practice doing, today. If there’s too large a discrepancy somewhere in that picture the next question is obvious: why don’t you do more?

Are you comfortable getting up in the morning, go to your job, come home and watch TV, go to sleep and rinse and repeat? Are you not doing something, or not doing more, because you’re afraid if you do your own private daily rinse and repeat routine will be disturbed?

It’s an interesting issue, to which extent we share responsibility for those around us, and for the societies we share with them. We need to realize that if and when we allow large, and growing, numbers of people around us to be desperate, the societies we cherish will of necessity change. When we allow more children to grow up in poverty, our societies will change for many years to come.

There’s no inbuilt mechanism that will revert them to a situation that we would prefer; we have to put in energy to make them what we would like them to be. Our rinse and repeat lifestyles put zero energy into improving, even maintaining, and so they deteriorate. Like anything else in the world.

And there’s always that same question: why do we allow for it to happen? Are our little private cocoon lives really so important to us that we willingly allow the world outside of them to go to hell in a handbasket? Do we just not care? Or do we maybe trust a bunch of people we vote for every so many years to solve all related problems for us, so we can watch TV?

In most western countries youth unemployment is over 25%, in some it’s much higher. For those young people that do find work, wages and benefits are much lower than for their parents’ generation. Still, these young people have to compete with their parents for the amenities of life, like housing, pensions etc., and they haven’t got a chance. Unless they literally fight. is that what you want?

The EU was supposed to be a union, all for one and one for all. But it hasn’t worked out that way. The richer countries have the edge over the poorer, and within nations the richer boomers squeeze the younger generation, their very own children. While all politicians, in every country and from every faith and creed, promise a return to growth waiting just around the corner that will solve all problems.

Not one even dare suggest that growth may not return, and that even if it does, it’s immoral to sacrifice millions of children’s lives while we wait for it. That in other words, a redivision of our wealth may be needed that enables the young to find a meaningful goal in life, even if the older generations would need to give up part of their lifestyles to achieve that.

The choice we are all making right now is to make our own riches more important than the poverty that is increasingly rampant among our children. It’s hardly a political choice, because our political systems don’t offer a way out. They offer different approaches to achieving – more- riches, but none to anything other than that. A true political choice would venture beyond that narrow frame.

If you vote, you vote for more growth, even if that’s an entirely obsolete thing to do. You do it anyway because it soothes your worries, and it allows you to think you can hold on to what you got. While most people in the west could be just as happy – or unhappy – with a bit less than what they have and spend so much time trying to keep. And while you try to keep holding on to it, it slips through your fingers.

And you tell yourself that child poverty is not really your fault. It happened while you were busy doing other things. Maybe it’s time to change your priorities. Like first make sure the society you live in is alright, that the people around you live good lives, and only after that put energy into increasing your own comfort level even more.

We are the richest people who ever lived, and who ever will. We are tens of millions of medieval kings and queens. What is it that is going so horribly wrong that we need to let our children live without purpose, even without food and shelter? I think it must be a short circuit in our brains.

Most of us could easily give up half our incomes and wealth and be at least just as happy, we could save the planet and do much more that would benefit those around us. But instead we choose to destroy it all, just for some imaginary wealth we don’t even need. And blame it all on someone else. It’s not our kids who are the lost generations, we are. We’re very busy losing everything.