‘Great performances in a lousy film,’ was the comment overheard as I left the Curzon Cinema in Mayfair after a Sunday matinee screening of AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY. I’m not sure about the ‘lousy’ part. Certainly, it is missing something as a drama, and I put it down to a safe deposit box.

It begins with the portrait of a marriage in decline. Beverly Weston (Sam Shepard) is a poet of repute who drinks. His wife, Violet (Meryl Streep) pops pills to ease her mouth cancer. Their relationship is described as ‘sickly sweet’. However, the film adapted by Tracy Letts from his Pulitzer Prize winning play and directed by John Wells, a veteran of TV’s E.R., is anything but. Insults and curse words fly. Relationships are either beyond repair of heading for disaster. Accommodation can barely be made. There is a near-silent point of view character, Johnna (Misty Upham), a home help of Native American extraction; the still centre of a mad, exasperating family who are collectively deficient in compassion.

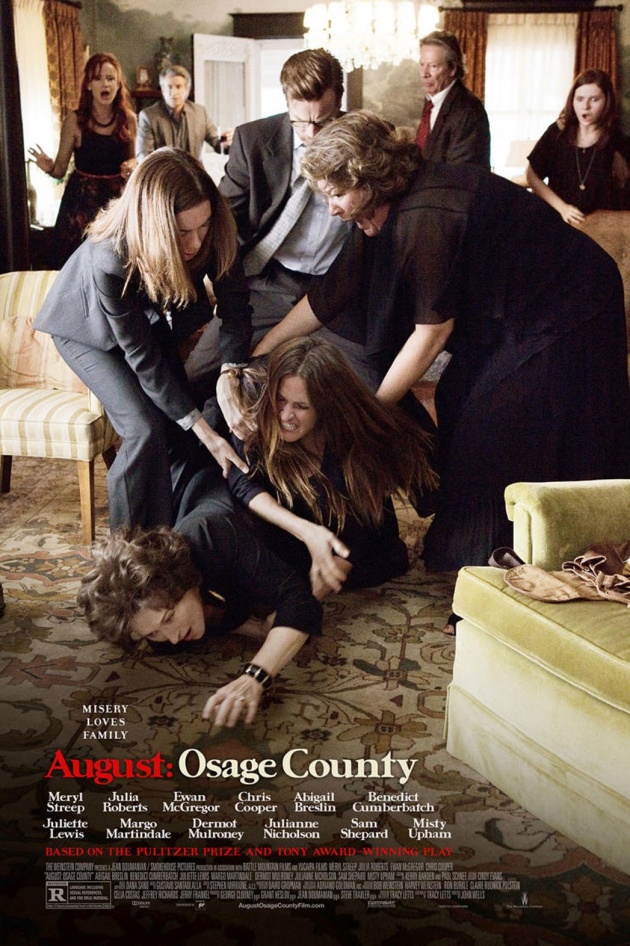

The reason to watch the movie is the Streep vs Roberts wrestling match, as featured on the US movie poster. Streep, a double Best Actress Oscar Winner (SOPHIE’S CHOICE, THE IRON LADY), is typically mannered. You watch her finger tapping on her lip, her posture, a phase below total bodily collapse. Violet is in pain and demands attention, but she expects it from her daughters not a stranger for a maid. Julia Roberts, single Best Actress Oscar Winner (ERIN BROCKOVICH), who has never sold out to a franchise unlike Halle Berry or Marion Cotillard, thank you very much (unless you count the OCEAN’S movies), plays the aggrieved eldest daughter, Barbara, who does not feel listened to. On a previous occasion, she tried to prevent her mother from going overboard with medication but then walked away, started a family, watched that fall apart as her husband Bill (Ewan McGregor) fell for a younger woman, apparently two years older than his daughter, Jean (Abigail Breslin). Roberts can do righteous anger as well as anyone. Her character is supposedly ‘a pain in the ass’ (Bill’s description) though I could not quite see it. She is presented as genetically disposed to bitterness and hate and you cannot entirely blame her.

The drama begins in earnest when Beverly disappears. Violet denies any knowledge of his whereabouts, but Barbara sees it differently. ‘He’s probably in a boat drinking and fishing.’ Barbara is right, but the boat is empty. Later Beverly’s body is recovered from the water.

Although there are mobile phones, one with a particularly grating ring tone, the drama doesn’t feel exactly contemporary. You feel the characters ought to be more connected, telephonically at least. Violet’s sister, Mattie Fae (Margo Martindale) has a son, little Charles (Benedict Cumberbatch) who is supposedly dumb, though some people perceive him to be interesting. ‘You have to be smart to be interesting,’ snaps Violet. He oversleeps, apparently, and misses Beverly’s funeral. Surely his mother or father could have phoned him to check that he was on his way. A revelation later on gives us a different take on this. Little Charles is keen to reveal his romance with Ivy Weston (Julianne Nicholson), the only one of Violet’s daughters supposedly not in a relationship, and has written a song (Cumberbatch has a good singing voice). You sense though that he knows the truth about himself and that he did not want to honour the man who never acknowledged him. This is not how the drama is played; little Charles is presented as a nervous, clumsy oaf who contributes to the dropping of a casserole dish.

The film is partly a comparison of hard childhoods. Between the aged of 4 and 10, Beverly lived with his family in a car. Violet was saved from brutal violence growing up by Mattie Fae, who took one in the skull for her. That, people, is a hard childhood, not emotional deprivation or neglect. Barbara’s complaint is that her mother all too easily plays the dependant, just giving in to those drugs. She wants her mother to accept that she is an addict and that her doctors – all of them – are culpable. There is a great scene that doesn’t go anywhere in which Barbara flings a series of prescription bottles at a local doctor – an accusation of culpability in her mother’s mental decline. I didn’t get from Streep’s performance that she was non-cognisant. There is one moment where she stumbles over words, but Violet seems – or is played – pretty sharp. ‘Nothing gets by me,’ is her refrain, and as uttered by Streep, the words don’t seem empty as they might if Violet was completely disengaged from her surroundings.

My biggest problem with the drama was the safe deposit box that holds the Weston family’s money and jewellery. I didn’t exactly follow Violet’s speech in which she describes what happened to it, but there is the suggestion that she claimed it before her husband got to it; that she did not come for him and consequently he killed himself. If you consider the hiring of Johnna as decisive, you might conclude as I did that Beverly hired a maid precisely because he knew he could not stand it anymore. There is no hint of this in Shepard’s performance – he dwells on the line ‘life is long’ as noted by TS Eliot. ‘A lot of people thought it, but he was the only one who wrote it down.’ There is the suggestion that the film deals with universal truths – men are sexually irresponsible and born cheaters, with the exception of Mattie Fae’s husband, Charles (Chris Cooper). The drama doesn’t feel universal because it never seems grounded in the everyday.

The sister who lives the most fantastical life is Karen Weston (Juliette Lewis) who ‘brings a date to her father’s funeral’ (Dermot Mulroney). The man is obviously a philanderer, married three times before – Violet fixes him with an accusing stare. The guy flirts with Barbara and Bill’s 14 year old daughter, which is a big no-no.

Truths are told and Violet is left almost alone. I never felt Wells knew how to shape the drama. Was it about how white American mid-Western ‘plains’ families are messed up; how they have no right to moral superiority. Or was it simply a more particular story with elements of Greek tragedy. The original play was some four hours long, but I felt that the film, which is half that length, should have been inspired by the play rather than an adaptation. The difference is in working out the through-line: who is our viewpoint character; what is different about the ending. Was Beverly’s death purposeful neglect and final punishment for an act several decades ago that went unpunished? The performances, good as they are, don’t clarify the meaning of the text. AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY isn’t a lousy movie, rather one that needs a re-edit.

Reviewed at Curzon Mayfair, Screen Two, Curzon Street, London, Sunday 9 February 2014, 12:30 screening