It is a brave film reviewer who writes off the talents of a once-bold auteur. On the basis on NYMPHOMANIAC, a four-hour, eight-chapter, two part film by Lars Von Trier, I am prepared to do it. It is the signature dish of a chef who uses ingredients past their sell-by date. It is at once self-indulgent, self-referential, vulgar, crass, distasteful and without serious intent. I concede that it is playful and betrays some element of craft. If I were Sam Taylor-Wood, I might concede that after Chapter Six of this film, a screen version of FIFTY SHADES OF GREY might be pointless. Then again, I thought that anyway. The purpose of this review is to negate the need to see Mr Von Trier’s movie; you may do so at the risk of tedium.

NYMPHOMANIAC is the first film by Mr Von Trier not launched at a major film festival. Until 2011, when he presented MELANCHOLIA, he had an open invitation to Cannes. However, in a Question and Answer session with the world’s press, he expressed some sympathy with Hitler. He did not so much poop where he ate, but emptied his entire innards, vital organs and all. This made him persona non grata, for which he probably has a stamp on his passport. MELANCHOLIA was, in the end, a fairly dreary affair, its conceit being that America, represented by 24’s Kiefer Sutherland could not save the world from a meteor, should one ever head towards us. l agree! It counts as hubris on our part if we think we can survive a cataclysmic event outside of our control. In MELANCHOLIA, such an event is a perfect reason not to consummate one’s marriage – that is between characters played by Kirsten Dunst and Alexander Skårsgard. The true subject of the film is obsolescence. Once a director embraces this, all storytelling is pointless.

Von Trier does of course miss the point of art, which is not just to acknowledge the things outside of our control, but to discuss how we conduct ourselves knowing that we cannot solve every problem. In order to live, it is necessary for us to forget that there are things we cannot stop. Rather we should simply concentrate on our choices. We attempt to be strategic – identify a high-level goal and try to achieve it. But with a slight remove, even the strategic can seem tactical, a small mitigation. Human history may at some point view socialism in this light.

NYMPHOMANIAC is a step backwards, a retreat from the abyss of obsolescence. It is a very 19th Century film about a woman, Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) who is found by a stranger, Seligman (Stellan Skårsgard) in an alley, bloody, bruised, no doubt with internal damage. Given a cup of tea and a bed, Jo is encouraged to speak, though when we see the pale drink poured by Seligman, you doubt its restorative qualities. She describes how she is a Bad Person. Already, we are outside the realm of recognisable human behaviour. If I had been the victim of violence, my body would be in a state of shock and I would be suspicious. A person who is lost tells their story; a person who is injured wants to take stock in their own sweet time.

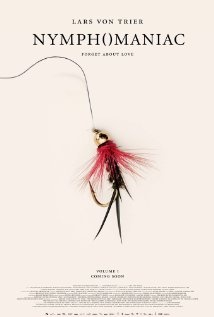

You have to suspend disbelief watching a Von Trier film; luckily for him, Hollywood and escapist literature in general has trained us for this. She presents her story in a self consciously literary way, taking inspiration from the room in which she has found herself. So Seligman is an accomplished fly-fisherman; Joe’s first Chapter is ‘The Compleat Angler’. She is, foremost, the nymphomaniac of the title. She recalls how she experienced sexual pleasure at a young age, pretending to be a frog, lying on the flat of her stomach on a wet bathroom floor, sliding around. At fifteen, she requests the loss of her virginity. A young man, Jerôme (Shia LaBeouf) relieves her of it in eight strokes, 3 + 5. Just to emphasize the point, the numbers are superimposed on the screen during the sex act (discreetly filmed, I might add, since there are conventions about filming under age sex). From then on, the young Joe (Stacy Martin) wants to have sex frequently and often. She and a friend board a train without a ticket and cruise the carriages for men to seduce. The two girls compete for a bag of sweets – candy-coated chocolate buttons – as to who can have sex with the most men. Joe loses on numbers, but gains extra points for seducing a man who is highly resistant to the idea of sex with a schoolgirl; he is saving his sperm for his ovulating wife and rushing home to her for the purpose of impregnation.

‘So you see,’ says Joe. ‘I’m a bad person.’ Seligman plays the apologist role, the middle European narrator figure who explains the female heroine by presenting her context - Gustave Flaubert justifying Emma Bovary, for example. Joe narrates her own story. In the context of cinema hers is experience mediated by the male listener, so it might just as well by narrated by the man, who chooses what is important – what do I relate to – and what to ignore. Seligman, whilst admitting he is a virgin (remember: please stow your disbelief in the overhead compartment) accepts the idea of women as sexualised pleasure seekers. So he doesn’t question her rejection of motherhood.

Joe repeats the mantra that ‘the secret to sex is love’; at which point we start to get bored. There are over three hours to go! In her second chapter, she gets an office job and has sexual relations with her boss, Jerôme, the very man who introduced her to 3 + 5; numbers in the Fibronacci sequence, no less. Joe has no office skills, yet in a later scene successfully parks a car (we see a diagram of the angle of approach). Please do not attempt to subject the film to logic.

I have not told you that Joe loved her father (Christian Slater) whilst thinking her mother (Connie Nielsen) was a ‘cold hearted bitch’. Why did I forget to mention this? Because it is a cliché and invites disqualification! Father is a doctor and loves trees. He talks ash. Joe is tremendously impressed and likes being told the same story again and again. A dull story does not get any more interesting in the re-telling. Joe is eventually abandoned by Jerôme when his uncle returns to work – he runs a printing company. She then takes multiple lovers.

The only chapter that has any sort of life is entitled ‘Mrs H’. Most of the characters are referred to as single initials, J, B and so on. You might conclude they bear some relation to values in an equation, though Von Trier doesn’t go that far. H is played by Hugo Speer, a married man with three young boys, who usually leaves in time for Joe’s Seven O’Clock appointment. Joe tries to end the relationship; he has no intention of leaving his wife, so, that’s it. But then H decides to move in. Joe does not protest; she keeps an open house. Then Mrs H (Uma Thurman) and her three young sons arrive at the flat, ostensibly to demonstrate to H the value of what he is giving up. She represents collateral damage, evidence of Joe’s amorality, though Joe at no point encouraged H to leave his wife; hers was not a challenge, rather a statement of fact. Thurman represents rage of the woman powerless to retain a loving relationship; her righteous anger displaces everything. It is raw. It is real. In the context of Von Trier’s cinema, it is futile.

I always thought that Von Trier was an exponent on the cinema of cruelty, itself derived from the Theatre of Cruelty of the early 20th Century. Suffering is shown without relief; this is the only point. It is demonstrated in the fourth chapter, ‘Delirium’ in which Joe’s father suffers a painful death. It is preceded, as Joe approaches the hospital where he is receiving ‘treatment’, by a quote from Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’. Joe’s father is meant to represent the idealised man, destroyed by forces he cannot control. He doesn’t have any recognisable condition, rather yells a lot, requires restraint and soils his bedclothes. It is a parody death sequence, one which has its origins in Act Four of any drama – there is always a tragic event to spur the hero on. It leads Joe to think she has found the perfect solution to her sexual desire – three men – in the chapter entitled ‘The Little Organ Book’, set to a Bach fugue. It ends with an announcement that Joe has lost all feeling below the waist. The audience had lost all feeling at the end of Chapter Three.

Volume II has three chapters and is far more violent and unpleasant than its predecessors, though its chapters are more like mini-movies, as in a portmanteau film. In Chapter Six, ‘The Eastern Church and the Western Church (and the silent duck)’ Joe recalls a hallucination of herself aged twelve framed by the Whore of Babylon and the most famous nymphomaniac in history - she’s floating. Seligman is of course appalled; she seems to be mocking Christianity, though I must confess that I couldn’t see it myself. After a brief interlude in which Joe recalls how she shoved several spoons up her vagina over lunch – an addition to the ‘classic restaurant scenes’ of cinema to add to Meg Ryan’s faked orgasm in WHEN HARRY MET SALLY – it describes how Joe becomes involved with ‘the dangerous men’. Here, the film becomes at first racially insensitive and then unpleasant. Joe wants to have sex with a man whose language she does not speak and gets a linguist to approach an African man on a street corner. He gives her the address of a hotel. However, he brings a friend. By this time, Joe is now played on screen by Charlotte Gainsbourg. The point of this scene is to have Joe/Gainsbourg framed by the erect penises of two African men arguing with each other in an unspecified language. We notice the length of their penises and the literally self-absorbed conversation; African men reduced to the primitive. I wasn’t offended by the naked penises, rather Von Trier’s reductionism. After all, he could have chosen to dignify the men with subtitles, to give them their voice – like Mrs H in Chapter Three. He chooses not to do so.

In order to recover her orgasm, she goes to a specialist (Jamie Bell) who, after initially trying to put her off, gives her the name of a dog (Fido) and subjects her to beatings, at one point administering forty lashes; Seligman complains that he got his reference to the Romans wrong. They administered lashes is threes. That’s why Christ only received thirty nine lashes. There is no point to this observation. Here, the film descends into FIFTY SHADES OF GREY territory. The specialist administers beatings but will not have sex with his patients. He gets them to make their instruments of torture.

At this point, Von Trier re-stages a sequence from one of his earlier movies, ANTI-CHRIST. The memorable opening features Gainsbourg and Willem Dafoe having sex as their young son leaps to his death. This time, Joe, now married to Jerôme, leaves her young son, Marcel at home alone while she waits for her beating. The boy, attracted by snow, runs to the ledge, but this time is saved. The sequence is meant to show how much Von Trier has mellowed; the children don’t have to suffer for their parents’ carelessness. You don’t believe it. Joe walks out on her husband and son on Christmas Day and never sees her child again. She kisses her specialist, but he doesn’t respond.

In Chapter Seven, ‘The Mirror’, she attempts abstinence and goes to a sex addicts anonymous support group. She tears down anything that reminds her of sex, but still she masturbates. In the final chapter, ‘The Gun’, she sets up her own business as a debt collector – actually she extorts money from men. In one scene, she breaks a man down by describing a walk in the park and the sound of swings; the man is attracted by children, specifically a young boy. The shame of his paedophiliac desire prompts him to cough up money.

There then follows the most dubious dialogue exchange in the whole movie. Von Trier’s thesis is that as children our perversity is polymorphic; we can be sexually satisfied by anything. Through childhood and adolescence, our desires are distilled into ‘acceptable’ forms. Paedophilia is presented as a ‘natural’ desire; Seligman praises men who know they are paedophiles but do not act upon it. ‘They should be championed as heroes.’ I felt this was Von Trier talking. If a paedophile doesn’t act on that desire, rather something else, doesn’t that desire take over? Therefore they are not paedophiles. Also when we think of paedophiles, we think of them practising it (or watching porn) rather than suppressing desire. A cinephile has to watch films to love them; a bibliophile reads books and so on. So there is no such thing as a passive paedophile; and why should the desire be natural anyway? The discussion has a place in a film about sex addiction but I think Von Trier needs to concentrate more on the addiction part; how we convince ourselves that we need a thing and that thing alone, which is surely part of social conditioning.

Joe isn’t getting any younger and takes on a protégée (Mia Goth) who has a deformed ear and is lousy at basketball. She becomes a mother figure, then a lover. She brings a gun to a job; bad mistake. In bourgeois dramas guns always go off by the end; NYMPHOMANIAC has a particularly trite ending, conducted in darkness (a black screen); the film opens and closes with the withholding of light.

NYMPHOMANIAC is undoubtedly the work of an erudite filmmaker, but it never comes to any great conclusion. Joe does not identify with Seligman and does not show him any compassion; she confirms her status as a bad person. What did we learn? People are what they say they are – steer clear. I don’t think that’s true. Self-understanding is an illusion. If Von Trier thinks he knows himself, he should stop making films.

Reviewed at Institut Français, South Kensington, Saturday 22 February 2014, 18:15 screening, simulcast at 74 UK cinemas.