Hepatitis

|

I |

INTRODUCTION |

Liver

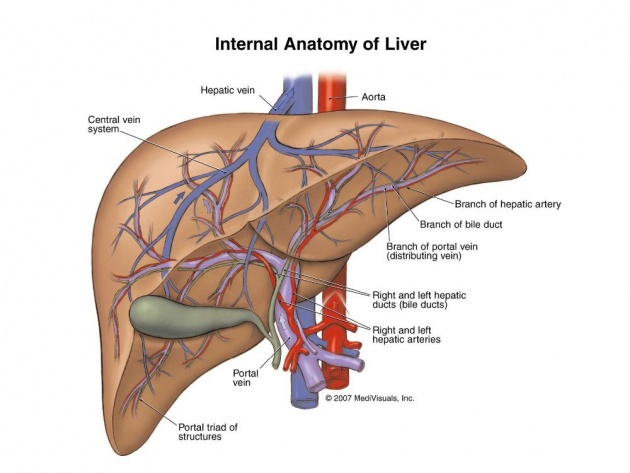

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver. The liver has many functions, among them the secretion of bile, a solution critical to fat emulsion and absorption. The liver also removes excess glucose from circulation and stores it until it is needed. It converts excess amino acids into useful forms and filters drugs and poisons from the bloodstream, neutralizing them and excreting them in bile. Hepatitis affects the liver’s ability to perform these life-preserving functions.

Hepatitis, inflammation of the liver caused by viruses, bacterial infections, or continuous exposure to alcohol, drugs, or toxic chemicals, such as those found in aerosol sprays and paint thinners. Hepatitis can also result from an autoimmune disorder, in which the body mistakenly sends disease-fighting cells to attack its own healthy tissue, in this case the liver. No matter what its cause, hepatitis reduces the liver’s ability to perform life-preserving functions, including filtering harmful infectious agents from the blood, storing blood sugar and converting it to usable energy forms, and producing many proteins necessary for life.

Symptoms of hepatitis vary significantly depending on the cause and the overall health of the infected individual. Some cases of hepatitis have few, if any, noticeable symptoms. When symptoms are present, they may include general weakness and fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, fever, and abdominal pain and tenderness. Another symptom is jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes that occurs when the liver fails to break down excess yellow-colored bile pigments in the blood.

In acute hepatitis, symptoms often subside without treatment within a few weeks or months. About 5 percent of cases develop into an incurable form of the disease called chronic hepatitis, which may last for years. Chronic hepatitis causes slowly progressive liver damage that may lead to cirrhosis, a condition in which healthy liver tissue is replaced with dead, nonfunctional scar tissue. In some cases, cancer of the liver develops.

|

II |

TYPES OF VIRAL HEPATITIS |

Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) lives in feces in the intestinal tract. It is spread when infected individuals do not wash their hands after using the toilet and then handle food, or when a person changes an infected infant’s diapers and then handles food before washing his or her hands. People who eat this contaminated food run a high risk of becoming infected. The virus also spreads when drinking water is contaminated with raw sewage. When people use contaminated water for drinking, as ice, or to wash fruits or vegetables, they run the risk of contracting HAV. Eating raw or partially cooked shellfish harvested from water contaminated with raw sewage can also lead to HAV infection.

Experts estimate that more than 50,000 people are infected with hepatitis A in the United States each year. Individuals with hepatitis A can spread the disease to others as early as two weeks before symptoms appear. In addition to the general hepatitis symptoms, such as nausea, fatigue, and jaundice, hepatitis A may also cause diarrhea. There is no treatment for hepatitis A. Most people will recover on their own without any serious aftereffects, although a few severe cases may require a liver transplant.

Hepatitis B Virus

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) lives in blood and other body fluids. HBV is transmitted from person to person through unprotected sexual intercourse with an infected person, or through the sharing of infected needles or other sharp instruments that break the skin. Babies born to an infected mother have a 90 to 95 percent chance of contracting HBV during childbirth. If a baby is infected, the virus remains in its body for many years, silently attacking liver cells and eventually leading to cirrhosis or, in some cases, cancer of the liver. Even though an infected baby may show few or no signs of infection, the infant continues to be infectious and can pass the virus on to others. In up to 10 percent of HBV infections, patients develop chronic hepatitis B.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes inflammation of the liver. The virus is recognizable under magnification by the round, infectious “Dane particles” accompanied by tube-shaped, empty viral envelopes. Manifestations of this condition include jaundice and a flulike illness, while chronic infection can lead to serious pathologies such as cirrhosis and cancer of the liver.

Although it has many different causes, hepatitis most often results from infection by one of several hepatitis viruses. All hepatitis viruses are contagious, but each is passed from person to person differently.

Experts estimate that there are more than 70,000 new hepatitis B infections every year in the United States. Drugs used in the treatment of hepatitis B include adefovir dipivoxil, interferon alfa-2b, pegylated interferon alfa-2a, lamivudine, and entecavir. Liver transplants may be beneficial to infected patients, but the virus remains in the body after transplantation surgery and may eventually attack the new liver.

Hepatitis C Virus

The hepatitis C virus (HCV), identified in the mid-1980s, is a slowly progressing infection that is primarily spread by intravenous drug users. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), anyone who received a blood transfusion prior to 1992, before an accurate routine blood screening was established, may be infected with this virus. HCV can also be spread through the sharing of toothbrushes, razors, and contaminated needles with an infected person; through unprotected sex with an infected person; and from mother to child during childbirth.

An estimated 30,000 cases of hepatitis C develop each year, and although some resolve spontaneously, 55 to 85 percent of all cases progress to chronic hepatitis. Most of the 3.9 million people with chronic hepatitis C in the United States do not look sick and may not even know they are infected. In 1998, a new combination of drugs was approved to treat hepatitis C. The therapy, a combination of interferon and the antiviral drug ribavirin, is currently the treatment of choice and rids the body of the virus in 40 to 80 percent of cases.

Hepatitis D Virus

Hepatitis D virus (HDV), found in blood, is transmitted through the sharing of infected needles or through sexual contact with an infected person. HDV is a parasite of HBV, using the B virus to reproduce itself and survive in the body. Only those infected with HBV are susceptible to HDV infection.

Hepatitis E Virus

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) lives in feces and is transmitted through contaminated food or water. Hepatitis E is found primarily in countries with poor sanitation.

|

III |

DIAGNOSIS |

Jaundice

Many types of hepatitis cause jaundice, a yellow discoloration of the skin, the mucous membranes, and the whites of the eyes. The yellow color is caused by an excess of bile pigments in the blood. The liver usually breaks down bile pigments, but when liver function is impaired by hepatitis, bile pigments in the blood build up and cause jaundice.

If the diagnostic symptoms of hepatitis—including an enlarged and tender liver, jaundice, and fatigue—are present, a physician may order tests to evaluate liver function, such as a blood test for excess levels of the bile pigments that cause jaundice. If liver malfunction is confirmed, the doctor may perform an ultrasound examination to exclude the possibility of gallstones or cancer. The doctor may take the patient’s medical history and ask about recent high-risk activities to further isolate possible viral or chemical causes. When the probable cause has been identified, the doctor may order specific laboratory blood tests to distinguish between different forms of hepatitis. The doctor may also order a liver biopsy, a procedure in which small samples of the diseased liver tissue are examined under a microscope to determine the extent of the liver damage.

|

IV |

PREVENTION |

Safe and effective vaccines are available to prevent hepatitis A and B infection. The CDC recommends that all travelers be vaccinated against HAV at least one month prior to traveling to developing countries with poor sanitation. The CDC recommends vaccination against HBV, which will also prevent HDV, for all newborn babies, infants, adolescents, and people in jobs that put them at risk for hepatitis, such as health workers. In the United States, the number of public school vaccination programs and other programs to vaccinate high-risk individuals is increasing. People who have not been vaccinated but are exposed to hepatitis may benefit from injections of immune globulin, a mixture of proteins in blood serum. Immune globulin injections can prevent hepatitis A and B infection if they are given within two weeks of exposure.

There are currently no vaccines available to prevent infection with HCV and HEV. The best protection against these viruses is to avoid high-risk activities, including preventing exposure to body fluids of infected individuals, and always washing hands after using the toilet or changing an infant’s diapers.