Above this proclamation is a name and dates of birth and death.

Poignant, yes, but also startlingly unique. Hers is probably one of the very few tombstones planted above the millions of dead in this country, that expresses an emotion.

That is just not how it is done in Pakistan.

Traditionally, when a marker has to be put up, it will carry a name, a date of birth and a date of death, along with a few religious inscriptions. That’s about it.

Rarely will any other detail of life be mentioned. Rarer still is any expression of sentiment.

Rites upon rites mark the first 40 days after a death, but the tombstone remains void of emotion. Almost all departed souls are dearly loved.

Why then, the reluctance to express it?

This is a land of raging feelings.

Drivers will scream, weddings will be week-long affairs, politics will be passionate, friends will be for life, neighbours will be nosy, religion will be second to none, cricket will be second only to religion.

Each citizen carries a lifelong pass to an emotional roller coaster entirely his own. But one trip to a graveyard is enough to dispel this image.

Who is buried under these depressingly sterile nameplates?

Are these the same people who in life knew not a single moment of staid conventionalism, for whom being alive was synonymous with being opinionated?

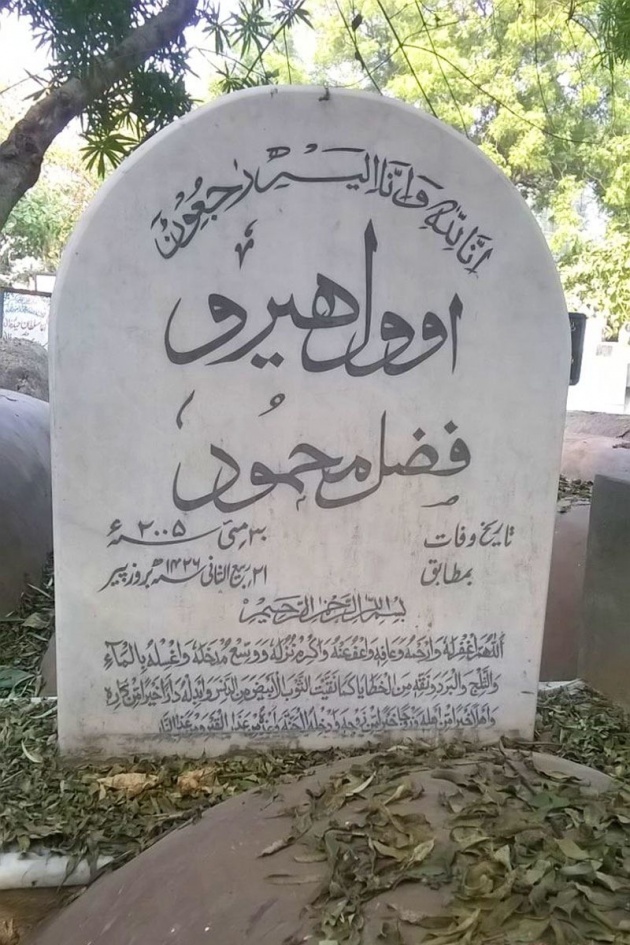

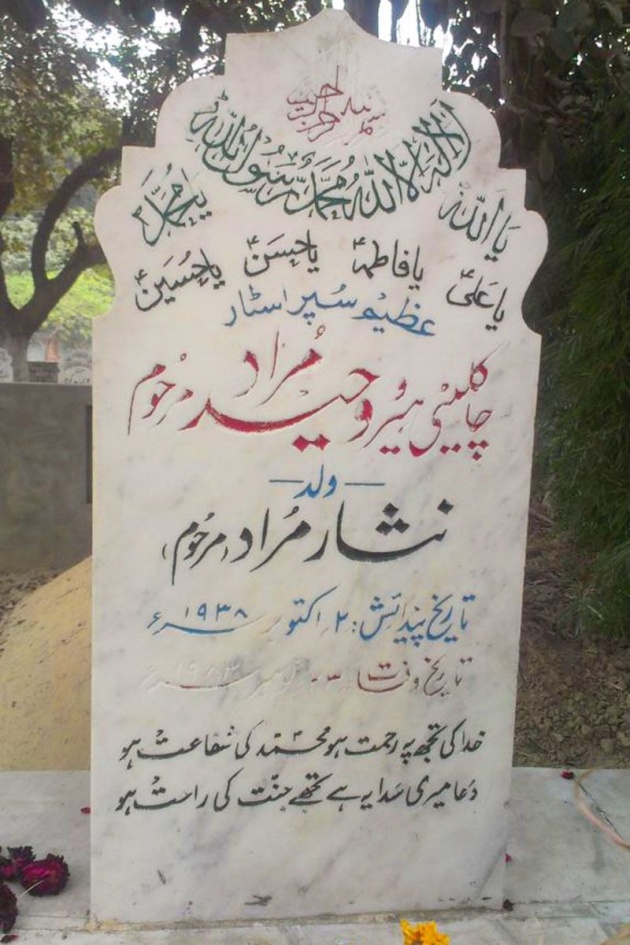

Many famous people of course do not fall into the above category. As in life, so in death, their fame is on display, marking them as different from ordinary folks.

Waheed Murad’s tombstone lets us know with no ambiguity that this was the “Great Superstar”, the “Chocolate Hero”. Fazal Mehmood’s has “Oval Hero” engraved on the back, the sound of those 12 fallen wickets still echoing five decades later. Allah Wasai, a queen to the last, is buried as “Noor Jahan, Malika-e-Tarannum”. Manto famously wanted his epitaph to be a challenge to God’s writing skills, but his relatives decided to make do with a less controversial message.