The government in those days grew obsessed with keeping Fatima Jinnah from expressing her views with freedom. Radio Pakistan once ceased broadcasting while Ms Jinnah made her speech on Quaid-e-Azam’s death anniversary. Qudratullah Shahab writes on page 432 of his book Shahabnama (1986):

After Quaid-e-Azam’s demise, rulers of the time did not give the deserved respect and status to Miss Fatima Jinnah. Two death anniversaries of the Quaid had passed, but Fatima Jinnah would not address the nation only because the administration would ask for her speech to be reviewed before broadcasting. This she never accepted. The rulers were afraid she would criticise the government or say things which shouldn’t be said.

Finally, in 1951, when the administration agreed to her demand, she went on air. It was Mr. Jinnah’s third death anniversary. During the speech, at one point, the transmission was stopped for some time. It then resumed after a while. It was later known that the parts of her speech in which she was criticising the government were censored and she did not get to know this during her speech.

There was a huge hue and cry over the matter. Newspapers the next day were full of condemnations and criticism. Although the Radio Pakistan administration kept insisting that the pauses in the transmission were due to technical reasons – specifically power outages – no one believed them. Everyone thought Miss Jinnah was deliberately censored from saying the things she intended to bring up.

Fatima Jinnah was not only Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s sister, but his guardian and political companion too. After Jinnah died, she was looked upon by people as a natural successor to her brother. But, there were forces against that idea, and they ensured that her voice was suppressed through various means, even literally, as explained below.

The government in those days grew obsessed with keeping Fatima Jinnah from expressing her views with freedom. Radio Pakistan once ceased broadcasting while Ms Jinnah made her speech on Quaid-e-Azam’s death anniversary. Qudratullah Shahab writes on page 432 of his book Shahabnama (1986):

After Quaid-e-Azam’s demise, rulers of the time did not give the deserved respect and status to Miss Fatima Jinnah. Two death anniversaries of the Quaid had passed, but Fatima Jinnah would not address the nation only because the administration would ask for her speech to be reviewed before broadcasting. This she never accepted. The rulers were afraid she would criticise the government or say things which shouldn’t be said.

Finally, in 1951, when the administration agreed to her demand, she went on air. It was Mr. Jinnah’s third death anniversary. During the speech, at one point, the transmission was stopped for some time. It then resumed after a while. It was later known that the parts of her speech in which she was criticising the government were censored and she did not get to know this during her speech.

There was a huge hue and cry over the matter. Newspapers the next day were full of condemnations and criticism. Although the Radio Pakistan administration kept insisting that the pauses in the transmission were due to technical reasons – specifically power outages – no one believed them. Everyone thought Miss Jinnah was deliberately censored from saying the things she intended to bring up.

The speech would not have damaged the government’s image as much as this act of cowardice did.

On October 7, 1958, martial law was imposed in Pakistan. Commander-in-Chief and self-proclaimed Field Marshal Ayub Khan was appointed the Chief Martial Law Administrator. The premier Mr Iskandar Mirza had done all this in order to maintain his hegemony on power. However, on the 24th of the same month, Ayub Khan robbed Iskandar Mirza of all his powers and set up a military government in the country.

Some of Ayub’s political advisors suggested to him that he should become the President of the country. And so, the ruling Convention Muslim League nominated him as a candidate. Opposition parties nominated Miss Fatima Jinnah to contest presidential elections against Ayub Khan. At first, she was reluctant, but she soon gave in to the idea.

The elections were held in January 1965. The opposition lobby believed that Miss Jinnah would sweep the elections. The results, according to the Election Commission, were on the contrary. Ayub had won. Pakistan was defeated.

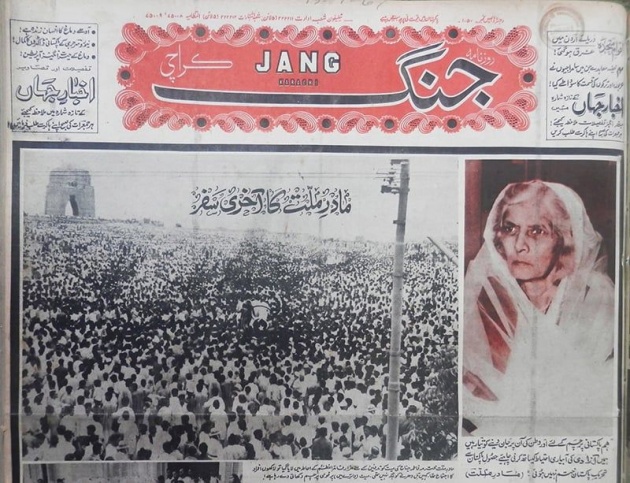

It was perhaps as a result of the acrimony developed during the election times, that the establishment made serious efforts to oppose Ms Jinnah's will – in which she asked to be buried next to her brother. There were serious efforts to bury her instead in the Mewashah Graveyard of Karachi.

I am producing here a rough translation of an excerpt from the book Maadar-e-Millat Fatima Jinnah (2000), by Agha Ashraf (page 184):

Miss Fatima Jinnah had expressed it while she was alive that after her death she be buried next to her brother. Now the problem was where to bury her, since according to Mr Abul Hassan Isfahani sahib, the government did not want bury her next to Mr Jinnah (M. A. H Isfahani’s interview, January 14, 1976). The government had to face tough opposition over the idea. Commissioner, Karachi was intimated that if Fatima Jinnah was not laid to rest next to the Quaid-e-Azam there will be unrest.