Ephraim Mizrakhi woke Zadok Cohen at 10:00 a.m. on April 16, 1983, the Sabbath. It had been a long night, with a new moon, and Ephraim had found it hard to stay awake while making his rounds. He had just patrolled the entire L.A. Mayer Museum, strolling past the vases and rugs, the darkened halls and the locked doors that kept the museum’s more valuable pieces safe. Then he went for a quick walk around the outside of the building, checking for unwanted visitors, but he saw nothing amiss. Soon it would be time for Zadok to open the doors, and for both of them finish their shifts. They would run through one final patrol at 10:30, twelve hours after their last night patrol, and then unlock the doors at 11 a.m.

Zadok stretched in his chair and yawned, glancing at the clock on the wall. The museum had closed at two the previous afternoon, in time for Shabbat, and they had been free to do as they pleased. Through the night, on a small television in the guard station, he and Ephraim had watched the Robert Redford film Jeremiah Johnson, about a hermit in the Rocky Mountains who fights against an onslaught of Crow Indians. The museum was quiet, an oasis high above the tumult of Jerusalem’s Old City; they usually did one or two rounds and then dozed in the office, confident that no intruder would disturb their sleep.

Now, Zadok walked past the staircase leading to the lower level and moved toward the family gallery, the room full of old clocks. Most mornings, he could hear them ticking, their strong springs still going after a night’s work. He knew that the family gallery held hundreds of horological marvels, and that most were in perfect condition. Sometimes they were a bit off, depending on the weather, but he could usually set his watch by them. The collection, people whispered, was estimated to be worth about $7.5 million.

As Zadok paused outside the gallery, he craned his head to listen. Silence. Maybe they had wound down. He stood there a few more minutes. No ticking. He put his key into the lock and turned. The heavy bolts slid back, and the door swung open. He caught a whiff of fresh air that gusted from the open window above the shattered glass cabinets and broken display tables. He rushed back up the stairs to the guard post, calling for Ephraim to contact Rachel Hasson, the museum curator.

Ephraim, after taking in the scene for himself, described it over the phone to Hasson: locks broken, trash scattered on the floor. The guard couldn’t say exactly what was missing, but it was clearly most of the collection. Hasson, “shocked” by what she heard, asked about the queen, the most important watch in the group. Zadok re-created the scene in his head, but he couldn’t remember seeing the watch amid the jumble of glass and wood.

Hasson phoned the keeper of the watches, Ohannes Markarian, then drove the few kilometers from her home in Rehavia, north of the museum. The then thirty-nine-year-old Hasson had started working at the museum in 1967, while it was still under construction, but even after all these years, her familiarity with the family gallery was limited. Her background was in Islamic art, and her mission was to bring Arab art to Israel. The watches, to her, had always been an afterthought. When she arrived, Markarian was already in the family gallery, running a tally of the missing pieces. He hid his eyes, for as they swept across the broken expanse of empty exhibits, they began to tear up.

If Breguet had been reincarnated, it might have been as Ohannes Markarian, the portly, bespectacled watchmaker who had maintained the L.A. Mayer collection for a decade before losing it on that morning in April.

In Armenian, Markarian’s language of birth, he was called a hanchar, a word that translated to “a genius who took great care of the talent that God gave him.” In Israel, for at least twenty-five years, he was considered the one man who could fix a timepiece and never have it break, a claim that his many satisfied customers repeated after leaving Jerusalem with their newly cleaned and tightly wound watches.

He was born in Istanbul in 1923. His family had survived the Armenian genocide, and after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the Markarians left Turkey. They settled in Jerusalem when Ohannes was four. At fifteen, he began his training in Old Jaffa, where he learned the prerequisites for watchmaking from a “very old man” who taught him carpentry, goldsmithing, and toolmaking. As he grew older and became more established in the watchmaking world, he realized that all of the ancillary techniques he learned from his master helped in his craft. Carpentry helped him rebuild broken clock cases, while goldsmithing taught him to be scrupulous with his materials. He learned to make very small things and very large things, and also learned to create his own tools when there were none to be found in the impoverished Old City.

He was talented at math and science and maintained high enough marks so that when he graduated he could have studied to become a doctor. But that type of training would have required him to leave the country. His grandfather, however, still bore the mental scars of the Armenian Genocide and said, “I have lost one family in Turkey. I’m not losing this one in Jerusalem.” Ohannes stayed put, instead becoming a doctor to old clocks.

At seventeen, he moved to Jerusalem’s Old City and apprenticed with a series of watchmakers who still kept stalls there. The winding passages of the ancient neighborhood were, like Breguet’s Place Dauphin, chock full of experts in every field. Markarian was able to refine his craft by working on ancient clockwork and modern wristwatches alike. There were two other watchmakers in the Old City at the time and they guarded their business jealously, an attitude still encountered there today. When I wandered into a watch repair shop by the Tower of David one summer afternoon to ask about Markarian’s old shop, the proprietor pretended not to know the location and then said “I’m the only Markarian you need,” as if the name of the master watchmaker now described a profession in itself.

As a teenager, Markarian turned his love of clockwork into a paid position with the British High Command, where he maintained office clocks and other delicate mechanical instruments used by the British authorities in Palestine. During World War II he worked for the British Army repairing naval and artillery instruments.

At twenty-five, he opened his own store in the Old City, on Christian Quarter Road, in a small, rounded stall with a large front room, a 10-by-20-foot rear storage area, and a small corner containing a restroom. Here he cared for and maintained a number of ancient clocks and watches brought to him by distraught curators. And here he kept his replacement parts – a collection that would soon engulf the entire shop – as well as all of his notes. He was a bookworm and meticulous note-taker, examining each piece of a watch and noting its design and problems in a series of notebooks. This habit helped him rebuild the watch when it was time to put all of the pieces together, and it also gave him an intimate understanding of every gear and cog in some of the greatest watches ever made.

He also helped maintain the bronze artifacts at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and recorded, in his head, a rich history of Jerusalem that he would expound upon from his small shop or over long lunches with friends and admirers. He amassed a personal collection that ran from thirteenth-century carriage clocks to modern quartz pieces. He began wearing a ring of watch keys on his belt, and as his business – and belly – grew he added more and more keys, resulting in a jingling, heavy collection that he carried with him at all times.

The two rival watchmakers in the Christian Quarter tried to keep up with Ohannes, but “everyone realized he was better than them,” said his daughter. Markarian became known as a horological miracle worker. A relative claimed that “when he fixed a watch once, it never needed repairs again,” and he was considered a master of mathematics, engineering and art. Those skills, coupled with his experience in metalwork, enamel and woodwork, encompassed everything he needed to know to be a master watchmaker.

His reputation expanded from his little shop and into the wider world. Slowly, business trickled in from Paris and London, then America and Asia. He was very protective of his watches, treating them like tiny, broken birds requiring a calm, careful hand. When he received a new watch for repair, he would spend hours – if not days – brooding over his bench. He sometimes brought his work home with him, but often left priceless horological masterpieces in his little shop. He trusted his neighbors implicitly, and knew they would deal quickly with anyone attempting to steal his broken treasures. When he finished with a watch, he would say, simply, “I made it tick again.” He said this thousands of times over his long career. When nearby shopkeepers came in to swap stories and gossip, if they saw him working at his bench they would quickly scamper off rather than risk his wrath at being disturbed.

In 1970, Vera Salomons hired him to prepare her father’s watch collection for viewing at the L.A. Mayer Museum, and from its opening in 1974, Markarian presided over the family gallery, maintaining watches so precious and delicate that he was often loath to wind them. But he visited at least twice weekly to wind, oil, and dust off the specimens. Many of them, Markarian said, kept time as well as a “brand new Seiko.”

With the esteemed Breguet expert George Daniels, Markarian created a color catalog of the Salomons Collection. Published in 1980 in West Germany, the 318-page book featured notes and images for every item, from the mechanical “Singing-bird in a cage,” a nearly life-sized bird that twittered and tweeted with the turn of a clockwork key, to the crown jewel, the watch they called the Queen.

On the morning of the theft, Markarian arrived at 11:39 — he was characteristically precise in noting when events transpired — as the sun was high over the pale stone of the museum. He ran to the family gallery and was horrified. The room had been ransacked, but he was surprised by how orderly it still was, even amid the chaos. There was little broken glass, just pita-sized circles cut out from the vitrines and placed carefully on the floor. Some empty food wrappers, Coke cans, and cigarette butts lay there, too, along with something that looked like a blanket, but nothing else was amiss. It was as if someone had come in, made very specific choices about what to take, and then calmly departed with the haul of a lifetime and one of the biggest watch heists in world history.

He saw where a line of modeling clay had been placed along the inside edge of the room’s door to prevent the guards from seeing light inside. The clay was devoid of fingerprints. A piece of black cardboard lay below a window that was slightly ajar. A seventeenth-century French table had been broken, probably when the thief dropped a bag onto it as he jumped down into the room from the window. The damage was limited but the theft complete. Markarian could hardly believe it; a large portion of the contents of the family museum, which had survived undisturbed for nearly a century, had vanished overnight. He walked wistfully past the holes and stands that once held the watches and clocks he had maintained for over a decade. He brushed his hand over the empty spaces and idly thumbed the curatorial notes that remained.

Moments later, the head of the museum board, Dr. Gavriel Moriah, arrived and surveyed the damage. Right away, he saw that the most magnificent pieces were gone: A singing bird gun (a clockwork novelty by the Roche Brothers, which played a jaunty tune on tiny whistles when wound and fired); a Swiss-made automaton of a walking woman; and almost all of the Breguet timepieces, including the Sympathetique, which used a main clock to wind and set a perfectly matched pocket watch, and, most devastatingly, the Queen. In all, the thief had taken one hundred watches, four oil paintings, and three antique books.

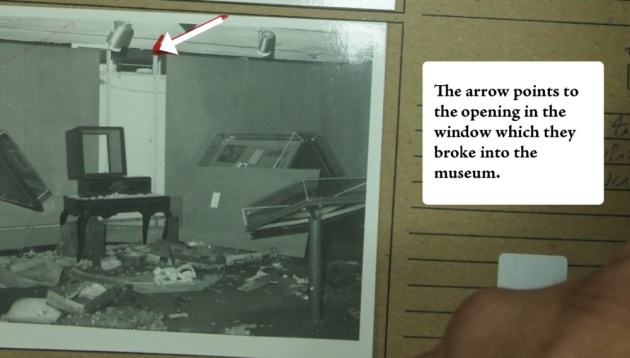

The police had been called, and the first officers on the scene found leftover strips of cloth that had apparently been used to bind the clocks for packing. The officers were amazed that anyone could have gotten the clocks out through the window, let alone that a human being could have slid through the tiny opening undetected. “Only people with a thin build could enter that narrow window,” an officer reported later, matter-of-factly.

An air mattress lay unfurled on the floor, probably used to cushion the fall of the equipment pushed through the small window. A can of Coca-Cola and a bag of sandwiches lay unfinished near one of the cases, and a bag nearby contained long-handled pliers and a heavy hammer. A rope ladder, probably a spare, was still in its original packaging.

By the size of the job, it looked to the police as if at least three men had been involved. That they were able to make off with over half of the collection in the course of an evening suggested that they had gathered all of the clocks together first, then quickly moved them out through the window. One man would have been inside, pushing the bags out, another outside, grabbing them, and a third one sitting in the car waiting for the getaway.

Felix Saban, Deputy Commander of the Jerusalem police, soon arrived with a mobile forensics van. His team traced the thieves’ steps from the side of the museum, where they must have parked, to the bent bars in the fence, to the climb through the thin window leading into the clock room. They began dusting for fingerprints, but this effort quickly proved fruitless — the room was already full of prints, and the thief had been unusually careful. The police were also surprised to find a listening device: a microphone by the door, attached to a wire running to an amplifier and a pair of headphones that the thief used to listen for the sound of footsteps through the door; there were some prints on the cable, but they were too fragmentary to be useful. Later, as the legend of the theft grew, some police officers would report seeing a half-eaten ham-and-cheese sandwich on the floor, seemingly a taunting gesture given the location and heritage of the museum. In truth, it was quite difficult, if not impossible, to get sliced ham in Jerusalem.

“This theft was more daring than sophisticated,” Ezekial McCarthy, the spokesperson for the Jerusalem police, told a Sunday newspaper. “The burglars knew the place well and did not leave themselves open to surprise. It is possible that they visited the exhibit several times and they may have also walked in with a catalog in hand and took only what was ordered by their higher-ups. They chose an amazing collection of watches and left a number of uninteresting ones, which suggests a selective knowledge.”

Another clue came from the tags stolen. Most of the watches and clocks had English and Hebrew curatorial notes, but the thieves had taken only a few, leaving behind the notes for paintings they took and some of the clockwork. This led police to believe it was a planned job, probably commissioned by a dealer in Europe. “They stole what was on their list, and would have been expecting payment for those items,” said a police officer. “The extra stuff [like the paintings] was, well, extra.”

On further investigation, the police discovered that, almost ten years after the museum’s opening, its directors were still bickering over what kind of security system to install. As a result, there was almost no security at all. The Jerusalem Post reported that “there was a single alarm for the entire building and this had never worked from the day it was installed.” Without the alarm active, the museum had security “about equivalent to that of a medium-sized kindergarten in an old neighborhood,” as one investigator said.

News of the theft spread quickly through the watch world and beyond. The Swiss watch industry was already suffering a major downturn and consolidation. Japanese quartz watches had decimated the market for low-cost mechanical watches. Smaller houses like Breguet, which had been in continuous business for two centuries, were out of money, and investors were swooping in to buy them in what amounted to a fire sale. Stories about the break-in appeared in the New York Times and the International Herald Tribune. Watchmakers were put on high alert; Interpol scrambled to monitor all prominent collectors moving in and out of Israel.

Gavriel Moriah, the museum board chairman, was certain that the thieves could not be working for a collector. “There’s no such thing as a collector who keeps his most prized possessions in a safe and never shows them to anybody,” he said. “A collector collects for gratification, and part of that gratification is to be able to show them off.”

An Associated Press story, which appeared the week after the theft, pegged the stolen collection’s value at $5 million and mentioned the most famous of the missing watches only in passing, describing it as built of “gold, crystal and glass.”

Ohannes returned home on Sunday after almost twenty-four hours of nonstop work. He fell, exhausted, into one of the kitchen chairs. His wife, after hearing the story of the break-in, stood quietly looking at her husband.

“You won’t have a job, now,” she said, finally. “What will you do?”

He shook his head. “They’re accusing me of the theft,” he said. The police had taken every staffer’s fingerprints, including his, but, for obvious reasons, his were the prints that showed up the most in the family gallery.

His daughter, Araxi, remembers the weekend vividly.

“He was very, very upset. I didn’t understand at the time, because I was too young. Nobody spoke to him in the house,” she said.

Mrs. Markarian told the children to play quietly. “Keep away from your daddy, he is very upset. The watches and the clocks have been stolen and they think he stole them,” she told them. Araxi’s sister Silva laughed.

“Why would he ever steal them? He’s the one who loves them the most!”

After the theft, Markarian did the best he could with the remaining timepieces, continuing to visit weekly to wind them. The museum loaned two of the clocks, one made by Hinton Brown of England in 1770, to the presidential palace, where they would presumably be safer.

Markarian gave tours of the remaining collection by appointment only, and one visitor remembers him sighing when he pulled open a drawer containing the boxes that once held some of horology’s most beloved masterpieces. He ran his hand along the indentations in the soft red silk where the watches once lay and then shut the drawer firmly, as if trying to forget the loss of his beautiful charges.

He missed all of the watches but the watch that pained him the most, the watch that would later be valued at $11 million dollars and hold the world, for a time, in a thrall, was the Queen, the eighteenth century’s most complex artifact, a watch of such beauty and precision and freighted with such tragedy that it would later become known simply as the Marie-Antoinette.