Signs and symptoms

Hypertension is rarely accompanied by any symptoms, and its identification is usually through screening, or when seeking healthcare for an unrelated problem. A proportion of people with high blood pressure report headaches (particularly at the back of the head and in the morning), as well as lightheadedness, vertigo, tinnitus (buzzing or hissing in the ears), altered vision or fainting episodes.[2] These symptoms, however, might be related to associated anxiety rather than the high blood pressure itself.[3]

On physical examination, hypertension may be suspected on the basis of the presence of hypertensive retinopathy detected by examination of the optic fundus found in the back of the eye using ophthalmoscopy.[4] Classically, the severity of the hypertensive retinopathy changes is graded from grade I–IV, although the milder types may be difficult to distinguish from each other.[4]Ophthalmoscopy findings may also give some indication as to how long a person has been hypertensive.[2]

Secondary hypertension

Some additional signs and symptoms may suggest secondary hypertension, i.e. hypertension due to an identifiable cause such askidney diseases or endocrine diseases. For example, truncal obesity, glucose intolerance, moon face, a hump of fat behind the neck/shoulder, and purple stretch marks suggest Cushing's syndrome.[5] Thyroid disease and acromegaly can also cause hypertension and have characteristic symptoms and signs.[5] An abdominal bruit may be an indicator of renal artery stenosis (a narrowing of the arteries supplying the kidneys), while decreased blood pressure in the lower extremities and/or delayed or absentfemoral arterial pulses may indicate aortic coarctation (a narrowing of the aorta shortly after it leaves the heart). Labile or paroxysmal hypertension accompanied by headache, palpitations, pallor, and perspiration should prompt suspicions of pheochromocytoma.[5]

Hypertensive crisis

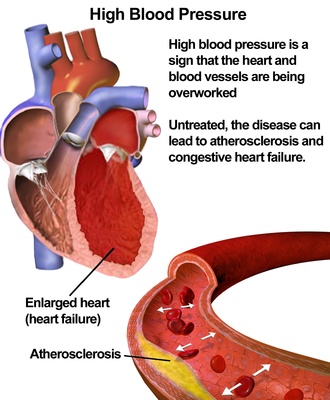

Severely elevated blood pressure (equal to or greater than a systolic 180 or diastolic of 110—sometimes termed malignant or accelerated hypertension) is referred to as a "hypertensive crisis", as blood pressure at this level confers a high risk of complications. People with blood pressures in this range may have no symptoms, but are more likely to report headaches (22% of cases)[6] and dizziness than the general population.[2] Other symptoms accompanying a hypertensive crisis may include visual deterioration or breathlessness due to heart failure or a general feeling of malaise due to renal failure.[5] Most people with a hypertensive crisis are known to have elevated blood pressure, but additional triggers may have led to a sudden rise.[7]

A "hypertensive emergency", previously "malignant hypertension", is diagnosed when there is evidence of direct damage to one or more organs as a result of severely elevated blood pressure greater than 180 systolic or 120 diastolic.[8] This may includehypertensive encephalopathy, caused by brain swelling and dysfunction, and characterized by headaches and an altered level of consciousness (confusion or drowsiness). Retinal papilloedema and/or fundal hemorrhages and exudates are another sign of target organ damage. Chest pain may indicate heart muscle damage (which may progress to myocardial infarction) or sometimes aortic dissection, the tearing of the inner wall of the aorta. Breathlessness, cough, and the expectoration of blood-stained sputum are characteristic signs of pulmonary edema, the swelling of lung tissue due to left ventricular failure an inability of the left ventricle of the heart to adequately pump blood from the lungs into the arterial system.[7] Rapid deterioration of kidney function (acute kidney injury) and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (destruction of blood cells) may also occur.[7] In these situations, rapid reduction of the blood pressure is mandated to stop ongoing organ damage.[7] In contrast there is no evidence that blood pressure needs to be lowered rapidly in hypertensive urgencies where there is no evidence of target organ damage and over aggressive reduction of blood pressure is not without risks.[5] Use of oral medications to lower the BP gradually over 24 to 48h is advocated in hypertensive urgencies.[7]

Pregnancy

Hypertension occurs in approximately 8–10% of pregnancies.[5] Two blood pressure measurements six hours apart of greater than 140/90 mm Hg is considered diagnostic of hypertension in pregnancy.[9] Most women with hypertension in pregnancy have pre-existing primary hypertension, but high blood pressure in pregnancy may be the first sign of pre-eclampsia, a serious condition of the second half of pregnancy and puerperium.[5] Pre-eclampsia is characterised by increased blood pressure and the presence of protein in the urine.[5] It occurs in about 5% of pregnancies and is responsible for approximately 16% of all maternal deaths globally.[5] Pre-eclampsia also doubles the risk of perinatal mortality.[5] Usually there are no symptoms in pre-eclampsia and it is detected by routine screening. When symptoms of pre-eclampsia occur the most common are headache, visual disturbance (often "flashing lights"), vomiting, epigastric pain, and edema. Pre-eclampsia can occasionally progress to a life-threatening condition called eclampsia, which is a hypertensive emergency and has several serious complications including vision loss, cerebral edema, seizures or convulsions,renal failure, pulmonary edema, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (a blood clotting disorder).[5][10]

Children

Failure to thrive, seizures, irritability, lack of energy, and difficulty breathing[11] can be associated with hypertension in neonates and young infants. In older infants and children, hypertension can cause headache, unexplained irritability, fatigue, failure to thrive, blurred vision, nosebleeds, and facial paralysis.[11][12]

Cause

Primary hypertension

Primary (essential) hypertension is the most common form of hypertension, accounting for 90–95% of all cases of hypertension.[1] In almost all contemporary societies, blood pressure rises with aging and the risk of becoming hypertensive in later life is considerable.[13] Hypertension results from a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors. Numerous common genetic variants with small effects on blood pressure have been identified[14] as well as some rare genetic variants with large effects on blood pressure[15] but the genetic basis of hypertension is still poorly understood. Several environmental factors influence blood pressure. Lifestyle factors that lower blood pressure include reduced dietary salt intake,[16][17] increased consumption of fruits and low fat products (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH diet)), exercise,[18] weight loss[19] and reduced alcohol intake.[20] Stress appears to play a minor role[3] with specific relaxation techniques not supported by the evidence.[21][22] The possible role of other factors such as caffeine consumption,[23] and vitamin D deficiency[24] are less clear cut. Insulin resistance, which is common in obesity and is a component of syndrome X (or the metabolic syndrome), is also thought to contribute to hypertension.[25] Recent studies have also implicated events in early life (for example low birth weight, maternal smoking and lack of breast feeding) as risk factors for adult essential hypertension,[26] although the mechanisms linking these exposures to adult hypertension remain obscure.[26]

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension results from an identifiable cause. Renal disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension.[5]Hypertension can also be caused by endocrine conditions, such as Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism,acromegaly, Conn's syndrome or hyperaldosteronism, hyperparathyroidism and pheochromocytoma.Other causes of secondary hypertension include obesity, sleep apnea, pregnancy, coarctation of the aorta, excessive liquorice consumption and certain prescription medicines, herbal remedies and illegal drugs.