By Bob Granath

NASA's Kennedy Space Center, Florida

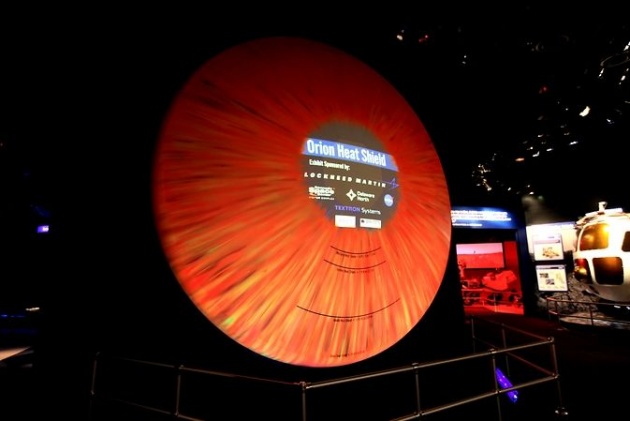

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex recently opened a new exhibit featuring a full-scale mockup of the agency's Orion spacecraft heat shield. The new capsule is designed to take humans farther than they’ve ever gone before and is scheduled for its first unpiloted test flight.

Earlier this year, engineers and technicians with Orion's prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, installed the largest and most advanced heat shield ever constructed on the crew module of the spacecraft. Tests of this crucial component is one of the primary goals of the upcoming flight test.

According to Sarah Hansen, communications coordinator for the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, the new display was designed to give guests a perspective on the size of the heat shield.

"The exhibit does a good job of showing how Orion's heat shield is so much larger than the ones used for Mercury, Gemini and Apollo," Hansen said.

The heat shield of the Apollo command module was 12 feet, 10 inches in diameter across the base. By comparison, Orion's heat shield has a 16.5-foot diameter.

The display is in the "Exploration Space: Explorers Wanted" area of the visitor complex with information on how the heat shield will protect the spacecraft during the heat of re-entry.

"The exhibit was built by Lockheed Martin with support from Textron, the heat shield's manufacturer; Delaware North, Ivey's Construction and Britts Air Conditioning," said Hansen.

The result is an exhibit that includes videos depicting Orion's assembly and simulations of its fiery re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere.

"The exhibit has a real 'wow' factor to it," Hansen said. "Our guests are coming away excited about the upcoming Orion launch."

NASA's Orion is mounted atop a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket at Space Launch Complex 37B at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. It is set to lift off Dec. 4 at 7:05 a.m. EST on a 4.5-hour, two-orbit flight. In addition to the heat shield, the test will evaluate systems such as avionics, attitude control and the parachutes.

During the second orbit the Delta IV Heavy's second stage will boost Orion 3,600 miles above the Earth. That will allow the spacecraft to hit the atmosphere with a high-energy re-entry at about 20,000 miles per hour.

The Orion crew module is the only portion of the spacecraft that returns to Earth. Its primary structure is made of aluminum and aluminum-lithium, with additional heat protection in the form of 970 tiles covering Orion’s back shell. The back shell tiles are almost identical to the ones that protected the bellies of the space shuttles as they returned from space.

Temperatures will climb highest at the bottom of the Orion capsule, which will be pointed into the heat as it returns to Earth. The heat shield is built around a titanium skeleton and carbon-fiber skin that gives the shield its shape and provides structural support for the crew module during descent and splashdown.

A fiberglass-phenolic honeycomb structure fits over the skin, and each of its 320,000 cells are filled with a material called Avcoat. That surface is designed to burn away, or ablate, as the material heats up, rather than transfer the heat back into the crew module. At its thickest, the heat shield is 1.6 inches thick, and about 20 percent of the Avcoat will erode as Orion travels through Earth’s atmosphere.

On this first flight, Orion will face temperatures near 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit during its return to Earth. That’s about 80 percent of the peak heating it would see during a return from lunar orbit in which temperatures could reach 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit. That is heat enough to give engineers on the ground confidence in the heat shield design for future missions.

Orion will eventually be boosted on missions beyond low-Earth orbit by NASA's Space Launch System to destinations such as an asteroid and Mars.