If you’ve been following the buzz around artificial intelligence lately, you may have gotten the impression that machines will soon take over the world and destroy it.

Hollywood is fueling the debate with the latest Marvel movie, Avengers: Age of Ultron, and Columbia Pictures’ Ex Machina — two films about what bad can happen when machines go rogue and utilize big data to render an unpleasant judgment on humanity, either because machines are so task-oriented and void of any reasoning or because the humans they are learning from are corrupt themselves.

Some of the tech world’s most prominent visionaries have weighed in on the issue, with seemingly uncharacteristic beliefs: Microsoft founder Bill Gates shared concerns about the threat artificial intelligence will pose to humanity, and theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, who relies heavily on machine learning and artificial intelligence to communicate, argued that it could spell the end of the human race.

Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk even likened AI to “summoning a demon.” Well, there was that time arobot vacuum tried to suck up a woman’s head as she was sleeping on the floor, as well as the various times GPS led people off a cliff, into traffic and into large bodies of water. So, it’s clear that there are many cases in which machines can work better for us, but are we overreacting to the supposed threat of technology?

After all, this isn’t the first time brilliant minds and alarmists predicted dystopia and got it wrong. Fifteen years ago, many feared that all computers would fail during the transition between December 31, 1999, and January 1, 2000, creating all kinds of chaos and possibly bringing on the apocalypse — and somehow we’re still here.

As former Chief Architect for Lockheed Martin’s Visual World Labs, I studied the relationship between humans and machines for many years; and from my view, the central issue of the 21st century is not machines taking over, it’s how to achieve the right balance between humans and automation to optimize outcomes.

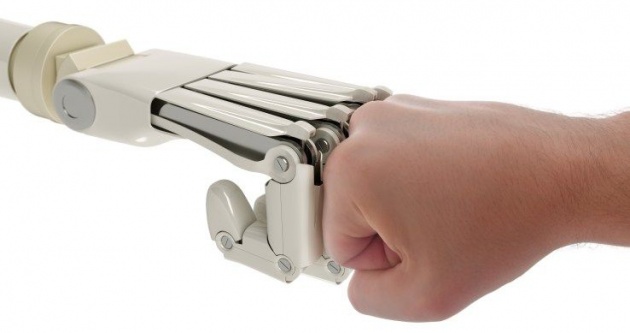

The most valuable resource we have in the universe is intelligence, which is simply information and computation; however, in order to be effective, technological intelligence has to be communicated in a way that helps humans take advantage of the knowledge gained. The optimal way to solve this problem is a combination of human and machine intelligence working together to solve the problems that matter most.

Soothing cultural anxiety is crucial to a foreseeable future with AI and machine learning; however, two of the biggest factors preventing this are fear and miseducation. People simply don’t know enough about how artificial intelligence and machine learning can benefit us; and from what they do know, the future looks like an epic battle scene between Skynet and Terminator. Now is the time to separate fact from fiction and explore the ways machine and human intelligence can and is working for us.

We’ve seen a good example in Google’s self-driving car, a six-year trial and initiative aimed at solving the age-old problem of auto collisions. The program’s director, Chris Urmson, shared in a recent blog post that of the 20+ cars driven by a team of safety drivers on the road, there were only 11 accidents across 1.7 million miles. Google maintained that the cars were not the cause of the accidents nor did any injuries occur.

In fact, the experiment allowed them to better understand patterns of minor accidents, which are rarely reported. They discovered that minor accidents occur more often on city streets than freeways, drivers are prone to different mistakes while driving at night versus during the day, rear-end accidents are most common and intersections are among the most dangerous places on the road. More importantly, they were able to use this knowledge to predict when an accident is likely to occur and avoid it.

The transition from propeller-driven aircraft to jet aircraft also gives us a good example of a defining moment in the balanced dance between the combined effort of human and machine.

Pilot training up through World War II focused primarily on pilot decision-making, eyesight and their physical skills operating the throttle, stick and pedals together. It wasn’t until we evolved to jet aircraft that the pace of human decision-making and the increased complexity of automated systems required a paradigm shift in training.

As jets began to replace propeller-driven aircraft, pilots were slow to accept their new role as a manager of the system, insisting on having complete control over every system in the machine, which resulted in a larger number of fatalities in early training, despite the fact that jet engine systems were more reliable and safer.

The core problem was that human brains had not had an upgrade since the Pleistocene epoch, yet jets required human decisions at more than triple the tempo of propeller-driven aircraft. The key to successfully flying a jet aircraft was learning what to outsource to the automated systems and what to retain for human management.

F35 pilots have taken this to a new level as each pilot is now equipped with their own “F35 brain” and when assigned an aircraft, the aircraft receives the brain specific to that pilot and their mission. So, each aircraft operates differently, tuned to each pilot’s preferences, and to the specific mission for that pilot.

The F35 helmet includes the ability to link the pilot with the sensors around the plane that allow the pilot to actually be able to “see through” the aircraft as if it were Wonder Woman’s invisible plane. Some F35 pilots have described the aircraft as an extension of themselves and some have even described dreams where they feel like they are fused with the machine.

We use words like “super-proprioception” to describe this feeling of man and machine combining with a fluid interface to enable new capacities that man alone or machine alone would not be able to accomplish. This is the harbinger of the new superhuman age. Hans Moravec describes this new age not as a threat to human dominion of the planet, but to a new age where we are fused with the exo-cortical extensions of ourselves to become “ourselves in more potent form.”

The future is bright as we’re starting to use what knowledge we do have to solve problems that save lives as with the use of micromappers to speed up response time and efficiency of disaster relief in Nepal. In all of these cases, we see that machine technology works best when it is informed by human behavior.

This is the ideal future of machine learning, where data is extracted only to benefit those it is extracted from, where machines don’t replace humans, but rather rely on human intelligence to translate patterns and behaviors into information that can change the world for the better.

Soothing cultural anxiety of AI and machine learning is paramount to its future. We can’t be too scared by unrealistic scenarios being proffered by some of our greatest minds or Hollywood, to prevent us from working in just the right mix of AI and machine learning to solve very real problems.

The good news is we’re getting there. Jet aircraft innovations are much more well-received, and a recent survey of U.S. consumers revealed that two-thirds would consider a self-driving car. nd while there are still legitimate concerns, we’ll begin to see a more harmonious balance of human and machine as we continue to dismantle fear, build trust and showcase the big-picture impact.