By adulating King for his work in the Civil Rights campaigns, we have misrepresented the complexity of those struggles and ignored some of the equally challenging campaigns of his last years.

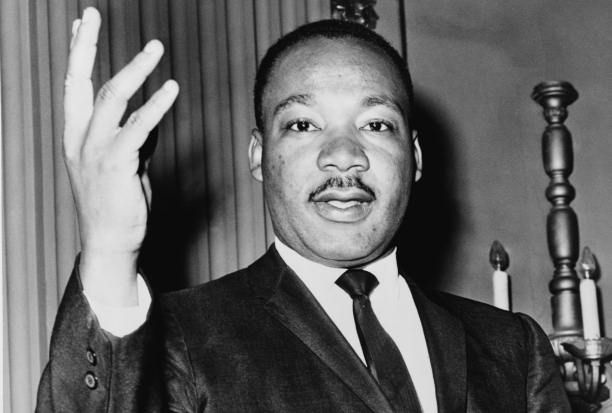

Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1964Martin Luther King is the only African-American honoured by a national public holiday. Decades after his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, the Martin Luther King remembered on such occasions is overwhelmingly the orator of 1963 who mesmerised a nation from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with the declaration 'I Have a Dream'. One of the first national events broadcast live and in full, the March on Washington, has provided sound-bites that have been used again and again. Alongside the images of President Kennedy's assassination in the same year, the King speech has become far more of an icon than a simple historical document.

Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1964Martin Luther King is the only African-American honoured by a national public holiday. Decades after his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, the Martin Luther King remembered on such occasions is overwhelmingly the orator of 1963 who mesmerised a nation from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with the declaration 'I Have a Dream'. One of the first national events broadcast live and in full, the March on Washington, has provided sound-bites that have been used again and again. Alongside the images of President Kennedy's assassination in the same year, the King speech has become far more of an icon than a simple historical document.

In recent years, however, historians have become unhappy with the distorting effect of the King legacy. The first sign of this discomfort, which reflects the misgivings of veterans of the Civil Rights movement, was the insistence that the movement was far more than Martin Luther King, Jr and that its achievements should not be ascribed to one man, however charismatic. More recently, this criticism has been enlarged by those scholars who have focused on the local struggles within which King was an occasional and sometimes marginal player.

This has been particularly the case in studies of civil rights activism in Mississippi and Louisiana. For specialist historians, the television montage of the movement, which has King in the lead role of a thirteen- or fourteen- year epic from 1954-55 to 1968, because of its emphasis on the 'war reports' from Montgomery in 1955-56 to the Selma-to-Montgomery march of 1965, fails to capture vital aspects of what made the movement possible and successful.

In 1995, Charles Payne in his award-winning account of the movement in Mississippi could argue persuasively that 'The issues that were invisible to the media and to the current generation of Black activists are still almost as invisible to scholars'. The King-centric popular literature, which scholars like Payne find especially culpable, is guilty not only of neglecting other actors in the civil rights struggle but of emphasising the first ten years of King's public ministry over the years that followed. There is a need to explore in more detail King's later campaigns from 1966 to 1968.

Looked at closely, King's successful national role was episodic and short- lived. The media did catapult the young preacher into the global spotlight in 1956 as the Montgomery Bus Boycott intensified. But, as the best scholar of King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Adam Fairclough, admits, the organisation's early years from 1957 to 1959 were 'fallow years'. A near fatal attack on King himself by a deranged black woman is commonly overlooked as one of the reasons why he had failed to develop a leadership programme by 1960. Yet there is some merit in the gripes of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) veterans that it was their initiatives in the form of the sit-ins of 1960, the Freedom Ride to Mississippi in 1961, and the voter registration attempts in the Magnolia state that did more to shape the movement than did any action of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. By 1962, for some hard-core activists, King seemed more a media figure than a true leader, getting headlines and donations largely for talk rather than actions.

It is worth noting the time span of just over six years between the settlement of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in December 1956 and the dramatic Birmingham campaign of April-May 1963 to underline the brevity of King's period of critical national influence that followed. This peaked in August 1965 with the passage of the Voting Rights Act and fell away steadily during 1966 with the setbacks of his Chicago campaign and the media's interest in the new protest slogan of 'Black Power'. Even if one stretches King's influence at the national level to February 1967, when his public denunciation of US involvement in Vietnam permanently closed the doors of President Johnson's Oval Office to him, his most powerful period was shorter than a single presidential term and considerably shorter than the public career that preceded it.

At the outset of his period of significant influence King had written the 'Letter from Birmingham Jail' in which he explained why he had led the protest campaign in Alabama's largest city. He explained his strategy of non-violent direct action as being organised 'to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue'. Such a creative tension was necessary to compel change since 'freedom is never voluntarily given up by the oppressor'. Much of the Letter was devoted to explaining the importance of protest to a white moderate audience alarmed by the spectre of social disorder. Such people had to understand the difference between laws that guaranteed justice and a legal system that preserved order. It was the inaction of people of so- called good will, King argued, rather than the activities of racial extremists that sustained segregation and racial discrimination. This emphasis on the political significance of the guilty bystander became even more central to King's thinking in the years after 1966 when he addressed the economies of racism and militarism.

It is misleading to portray the Civil Rights movement as exclusively a southern struggle intent on ending desegregation and disenfranchisement in the South. In the early 1960s national leaders like the trade unionist A. Philip Randolph and black figures within northern radical circles recognised dangerous trends in employment, education and housing discrimination. The famous March on Washington was officially a march for jobs and freedom and, in addition to crowds attracted to the fiery separatist rhetoric of Malcolm X, there were major protest campaigns in Boston, Chicago and other northern cities well before 28 blacks died in the Watts disturbances in August 1965. Nonetheless, King was as ill-prepared to launch an effective assault on ghetto problems in 1966 as he had been to orchestrate an attack on legal segregation in the south in 1957. But, given his belief that a failure to act against a social evil made one complicit in its perpetuation, he had no choice but to offer a programme, especially when it appeared that other Sources of non-violent leadership, notably SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality, were no longer committed to non-violence.

By the same token, while King recognised that speaking out against the Johnson administration's policy in Vietnam would attract enormous criticism, he could not remain silent without giving Sustenance to a gross evil. Biographers report how he was deeply shaken by pictures of Vietnamese casualties of the intensified bombing campaign and decided that in conscience he had to speak out. At New York City's Riverside Church on April 4th, 1967, King denounced his own country as 'the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today'. Linking the deepening crisis in America's ghettos with the escalating military expenditures in Vietnam, he warned the bombs that were dropped in Vietnam would explode at home. 'The security we profess to seek in foreign adventures,' he warned the crowds at an anti-war rally at the United Nations building later that month, 'we will lose in our decaying cities'. Giving credence to this warning, major civil disturbances in Newark, Detroit and other cities that summer resulted in massive destruction of property, injuries and deaths.

In this desperate context, King agreed to attend the National Conference for a New Politics in Chicago in August 1967, which was supposed to provide a programme for radical-social change. Previously derided by militants for maintaining links with the political establishment, King indicated that SCLC planned to end its affiliation with the Democratic Party. Speaking in a manner not heard from a national African-American figure since anti-Communist attacks silenced the socialist educator W.E.B. Du Bois and the singer Paul Robeson in the early 1950s, King denounced capital- ism and urged a guaranteed minimum income. The West, he added, should not oppose but should support Third World revolutions. Deaf to King's radicalism, many in the audience of New Left activists and Black Power militants jeered or walked away. Rejected by the self-declared revolutionaries, and alienated from the Cold War liberals who dominated the Democratic Party, King searched for a new strategy. His public standing was so dubious that black electoral candidates like Carl Stokes, who was elected mayor of Cleveland in 1967, preferred to downplay King's role in their campaigns.

King had never been a master strategist. Others had launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Birmingham and Selma movement, and some of his young lieutenants, notably former sit-in student James Bevel, were more adept tactically. It was Bevel who had recognised the value of recruiting children to march in Birmingham and who urged the use of 'coercive' non-violence to prevent the existing social order from conducting 'business as usual'. Predictably, therefore, the idea for the Poor People's Campaign (to pressurise the federal government to withdraw from war in Vietnam and to intensify instead the War on Poverty), although built logically on the philosophy of non-violent direct action enunciated in the 'Letter from Birmingham Jail', was the brainchild of Marion Wright, a black lawyer with strong ties to the Mississippi movement. Ironically, the plan to have the nation's poor converge on Washing- ton for a campaign of non-violent direct action was also far more similar ' to A. Philip Randolph's original March on Washington movement of 1941 (which protested at African-Americans being excluded from defence employment) than was the 1963 event that had confirmed King's pre-eminence as a race leader. Like the earlier set piece campaigns of SCLC, it would seek to induce sufficient creative tension to compel Congressional action. As King told a BBC correspondent only a week before his assassination in 1968, 'We're going to escalate non-violence and seek to make it as dramatic, as attention-getting, as anything we did in Birmingham or Selma, without destroying life or property in the process.'

In the event King did not live to see the Poor People's Campaign and its failure can at least partly be attributed to the organisational confusion that followed his sudden death.

However, the campaign marked a significant departure from his previous campaigns. Unlike Birmingham or Selma or even Chicago, it did not seek to build on existing local protest activities in their home bases but to take local movements onto the national stage by moving them to the capital. In doing so, SCLC organisers underestimated the resources needed to sustain such a transplanted community. When the campaign occurred, Resurrection City, as the Poor People encampment was called, absorbed much of SCLC's energy.

Whereas earlier campaigns had tried to use the leverage of a federal political system to bring national power to bear against local state and city power, the Poor People's Campaign targeted the Federal Government in the expectation that the disruption of normal practice and the pressure from a sympathetic public audience would revise the Congressional agenda and re-shape policy. The peculiar status of the District of Columbia as the creature of Congress facilitated this focus on the Federal Government, but complicated public perceptions. Non-violent demonstrators were no longer confronting authorities in somebody else's community but in every American's capital city. In previous campaigns, the tension between national embarrassment and local resentment had tended to favour peaceful demonstrators but in 1968, in a context of increasing insecurity and conservatism, they operated mainly against the movement.

The Poor People's Campaign also repeated the same tactical errors that had helped to frustrate the Chicago campaign of 1966 in that it had too many targets. By concentrating on the right to vote in Selma, the SCLC had dramatised the need for federal voting rights legislation. It was unrealistic to suppose that a militant Poor People's Movement could be organised in nine months so as to command sufficient resources to compel the Federal Government to reverse established policy in many different areas. To those who argue that King might have provided sounder guidance in this respect than did his success or, Ralph Abernathy, one can respond that the last year of King's life was characterised by an escalation of his goals rather than a shrewd selection of immediate aims. His decision to go to the aid of the striking Memphis sanitation workers in March 1968 was symptomatic of this tendency. In 1966 the SCLC had struggled to manage the difficulties of handling many local groups in Chicago, yet in 1968, at a time when the factionalism within the movement had intensified, it proposed to unite an even more diverse coalition.

So, what does a focus on the 1966-68 period rather than the 1963-65 period of King's career reveal about him? One argument would be that it provides a vantage point from which to see the weaknesses within his leadership. In essence, he repeated mistakes. He needed to learn more about the ghetto before he could attack it, just as he had needed to know more about the rural Deep South before he could organise effective campaigns there. He needed to adapt his repertoire of non-violent tactics, which had relied heavily on the cumulative and interactive impact of economic pres- sure and media censure, to a new terrain and new objectives. Despite the pressures from unfulfilled expectations and worsening economic and political indicators, King needed to have more realistic tactical objectives. As he himself told a press conference in 1967, he needed a victory, even a limited one, to retain credibility in the context of rival calls separatism.

The ultimate charge in such a critique is one of hubris. King believed that he was the only one who could address the ghetto crisis non-violently and, with equal fervour, he believed that the Nobel Prize and his own Christian ministry had made him an anointed international champion for peace. This led him to dissipate his own and SCLC's energies outside of the South and the immediate needs of African-Americans in that region. At a time when effective implementation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 provided the potential for a genuine political reconstruction, SCLC continued to devote much of its depleted re- sources to Chicago and King himself was prepared to sacrifice his access to the President by his pronouncements on foreign policy.

The criticisms against King seem largely to boil down to a condemnation of the philosophy of non-violent direct action. Consistent with his axiom that 'Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere', King believed that he had to provide an alternative to urban conflagration as a means of signalling the plight of inner-city dwellers. Similarly, being convinced that evil was sustained more by the inaction of others than by the deeds of the wicked, he felt unable to stay silent while the United States pursued a foreign policy that entailed wanton warfare against a people who had not attacked the United States. Rather than lamenting the failure of King to mobilise enough support to end the war in Vietnam or to shift government priorities back to the issues of social and economic justice, it seems more useful to reflect on the accuracy of his analysis.

Was he wrong to stress that uneven distribution of wealth was crucial to the persistence of racial inequality? At a time when indices suggest that the gulf between rich and poor, black and white, is widening in the United States, one would have to accept his diagnosis. If the South that emerged after the Voting Rights Act did not fulfil the hopes of those who dreamed of a more egalitarian and more tolerant America, was this not due more to the failure to re-educate white southerners than to a failure of African- American leadership? Similarly, if King's calls for America to make the elimination of poverty its priority failed to prevent the impoverishment of the unskilled working classes since the 1960s, surely this was due to a lack of moral commitment not from King, but from so many of his contemporaries? Thirty years after his death, King's concept of the guilty bystander still points us to the injustices that we support by our inaction. We each make history by the causes we pursue, but much more commonly by the many times we stand aside.