Since 1848, when Kempsey National School became the first school to join the government education system in New South Wales, another 7,396 schools have opened during the system's 150 years. Some have flourished, others have languished, while most, having served their purpose, have closed. As only 2,243 government schools (including 23 Environmental Education Centres) were open in 2007, it can be appreciated that many more schools have disappeared than are currently open. Yet these 5,151 closed schools form as much a part of the history of education in this State as do the open schools. What has been done, therefore, is to provide a list of every government school in the State since 1848 together with its operational details and approximate location.

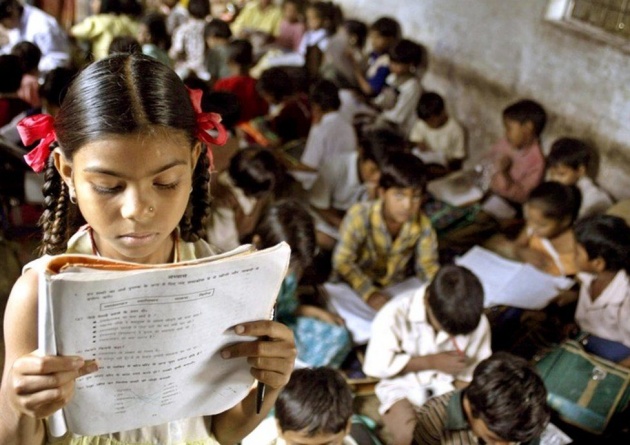

If all government schools had been like Kempsey National School, a plain elementary school, it would have made their listing so simple that other sections of this website, such as the Glossary of Types of Schools and the Changes of name would have been unnecessary. A table or two would have sufficed to show the development of the school system since 1848, with a few notes to explain why the numbers rose or fell at particular times. As it happened, over 30 different kinds of government schools have been in existence at one time or another, each with a specific purpose. Some have catered for children isolated by distance; others have been created in order to separate children according to their age, sex, race, mental and physical abilities, or vocational aspirations.

Definition of a government school

A government school is here defined as one under the control of the Board of National Education (1848-1866), the Council of Education (1867-1880), the Department administering education since 1880 (see Administration of education in Facts and Figures section), or one under another government department. Private, subsidised and denominational schools, even when they received government aid and were subject to some form of government control, are not included unless such schools were later absorbed into the government school system, in which case they have been dated from the time they were taken over by the government authority.

The purpose and development of the different types of schools

Given the complexity of the government school system over the period, it is necessary to explain, at least briefly, the purpose and development of the different types of schools. What follows, then, is more a history of schools than of education: changes in pedagogy, educational psychology, teacher training, and the other strands that together make up the history of education have been touched on only when they throw light on the development of the various types of schools.

Links between the State and the Anglican Church

Had the colony established in New South Wales in 1788 followed British precedent, the education of the 'lower orders' would have been left entirely to the churches or other agencies. In a struggling convict settlement, however, voluntary resources were inadequate for such a task, and from early in the colony’s history the governors granted State assistance, especially to the Church of England, to establish and maintain schools. The link between the State and the Anglican Church became so strongly forged that in the 1820s a corporation was formed by royal letters patent and given one-seventh of all New South Wales land for the maintenance of the Anglican Church and 'the education of the Youth in New South Wales'. Other Christian denominations in the colony fiercely challenged the notion of an Anglican religious and educational monopoly. Their hostility, together with political changes in the mother country which allowed greater freedom for Catholics, and growing objections to the alienation of large tracts of colonial land with no possibility of their development led to the dissolution of the corporation.

'Common school' system

Thus in the early 1830s Governor Bourke was faced with the problem of promoting education in a way which did not favour any particular Christian denomination. His first thought was to grant aid proportionately to each denomination, but he soon realised that the establishment of three or four schools in every small community in the colony to cater for the various denominational groupings would be an extremely wasteful and socially divisive system. Bourke decided to introduce a "common school" system along the lines of the Irish National System he had seen at work in Ireland, where Catholic and Protestant children attended the same schools. At these schools pupils received an elementary education, and the problem of different religious backgrounds was overcome by the use of a book of scripture readings; in addition, local clergy had access to their flock during school hours to give instruction in specific doctrinal matters.

Protests

Bourke's proposal was stoutly rejected by the Protestant sector of the population, Anglican clergy in particular, on the grounds that the use of scripture extracts was tantamount to a ban on the use of the whole Bible in schools; that in itself was unforgiveable, and it appeared to Protestant Bible reading minds too much of a concession to the Catholic party. The Irish National System, despite the obvious need for such a system, was put to one side and a pound for pound subsidy allowed to each denomination for the cost of schools.

Subsidies

In the late 1830s Governor Gipps came to the same conclusion as Bourke had come to some years earlier in regard to the unnecessary duplication of schools under a denominational system. Believing that Bourke's proposal had been unacceptable to the Protestant denominations because it included Catholics in the same system, Gipps proposed a common school system for Protestant children and a continuation of the subsidy for Catholic schools. As before, Anglican hostility to the scheme, this time because it excluded the teaching of specifically Anglican doctrine, led to its withdrawal.

The establishment of a public education system

During the 1840s there was a weakening in the power of the Anglican Church to resist the introduction of a government system of schools. A report of a select committee in 1844 pointed out that, because half of the colony's children of school age were not under instruction, the denominational system of schools had failed; it recommended the introduction of the Irish National System. In addition the severe depression in the 1840s reduced the Church's contributions to such an extent that even on a pound for pound basis it was difficult to maintain existing schools, and almost impossible to establish new ones in the rapidly expanding country areas. A compromise was arrived at whereby the Anglican Church withdrew its opposition to the Irish National Systemon the condition that government subsidies for denominational schools were continued. Consequently, in September 1847 the Legislative Council placed £2,000 on the estimates for the establishment of schools similar to the National Schools in Ireland. In January 1848 Governor Fitzroy appointed the Board of National Education to undertake the task of creating the necessary government schools and establishing a public education system; simultaneously, Fitzroy appointed the Denominational School Board to handle government subsidies to church schools.