Image credits: Exhibition title by Naotalba

Recently, I noticed a new exhibition for the summer at the Museum of London Docklands, titled Roman Dead: Death and Burial in Roman London. Prompted by the discovery, in 2017, of a Roman sarcophagus near Harper Road (Southwark), this exhibition aims at exploring how people dealt with death and burials, as well as how they lived, back when London was still called Londinium.

Location

When: May 25 to October 27, 2018, at the Museum of London Docklands (www.museumoflondon.org.uk) on West India Quay (Canary Wharf).

The closest Tube stations are Canary Wharf (Jubilee line and DLR), West India Quay (DLR), and Westferry (DLR).

Image credits: Grave goods and bones, by Naotalba

The Art of Dying

The whole exhibition offers insights as to how Romans in Londinium approached death. Therefore, it obviously has its share of actual skeletons and funeral items.

Funeral rites

The Romans believed that the souls of the dead lingered between the world of the living and the world of their ancestors. During this transition period, the deceased's family was considered as unclean, and only proper funerary rites could cleanse them. The burial rites were normally performed between two and seven days after death. They were very different depending on the person's status. Poor families could only afford private burials, while wealthy ones had processions and musicians, and a nine-day long feast.

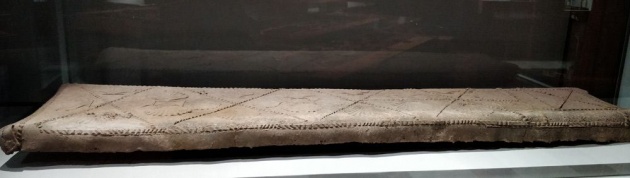

Image credits: Sarcophagus lid by Naotalba

Burials and pyres

The Romans first favoured cremation, as a way to transform and purify the body. However, by the third century AD, this had changed, and people in Roman London were most often buried. One reason is that cremation at the time involved placing the body on a funeral pyre. So much timber (700 to 900 kgs of wood per pyre!) was expensive, and thus reserved for important personalities.

Most people were laid to rest underground, but some of the wealthiest inhabitants had their own mausoleums (small buildings containing sarcophagi and grave goods), or had their burial site marked with large monuments instead of small tombstones. Such monuments attracted attention and helped the living better remember the dead.

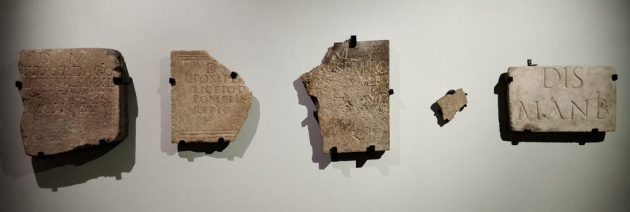

Image credits: Tombstones by Naotalba

Grave goods

The exhibition offers a variety of grave goods on display: jewellery, urns, everyday objects...

Why were these goods left in graves? To reflect the deceased's personality? To help them travel in the afterlife (shoes and food)? The reasons remain, at times, unclear. Some objects were very expensive at the time, which shows that the Roman population in Londinium also had its share of wealthy people. Also, many items found in ancient cemeteries weren't made on what would become British soil, but brought from various places throughout the Roman Empire.

Image credits: Expensive millefiori glass dish via https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk

Skeletons

In the middle of the exhibition area lay the skeletons of several Roman Londoners, both adults and children, also excavated in the London area. Some could be almost entirely pieced back together, others clearly were incomplete.

Image credits: Skeleton by Naotalba

Note that the 2017 sarcophagus and its occupant are, of course, also displayed.

Children

A part of the exhibition I found really interesting, albeit disturbing, was how Londinium people (following Roman practice) dealt with the death of their children. For starters, due to high infant mortality in general, a child wasn't named before they were 9-day old. And they were only considered as fully developed after their started teething. Stillborn babies, and babies who died before their sixth month, were seldom buried in cemeteries. Instead, their remains lay in tiny crates, sometimes in gardens or under house floors.

Image credits: Remains of a baby's skeleton found in a crate, by Naotalba

Even now, we're unsure whether this showed a lack of care, or a way of keeping the child close.

One of the tombs revealed the remains of an adolescent male and two children, buried together. But we don't know if they died at the same time, or if that was a family tomb.

Image credits: Adolescent and two children, by Naotalba

Mystery burials

A few burials remain unexplained, like decapitation burials, where the deceased's heads were placed somewhere else in the grave. The reasons are unknown—those heads were only cut after death. Was this out of reverence, or to prevent the spirits of the dead from coming back?

Image credits: Decapitation burial by Naotalba

In other cases, people were buried with iron shackles at their legs or wrists, placed there after death, too. Perhaps the aim here was also to prevent them from walking back to the living world?

Scientific analysis

Since we've found so few remains in London, there is still much we don't know, and a lot we had to reconstruct through scientific methods.

(The exhibition shows several videos explaining the analysis processes in more details. I shot a few, but had to edit out sound due to noise. Fortunately, they all have subtitles.)

Video credits: Why do we study human remains? filmed by Naotalba

For instance, we can analyse aDNA (short for 'DNA sampled from an ancient source'), or study teeth and bones to find out a person's diet. This leads in turn to other discoveries: minerals in bones also tell us about where a person grew up.

Below, you can see the examination of the Southwark skeleton discovered in 2017:

Video credits: Examining the skeleton, filmed by Naotalba

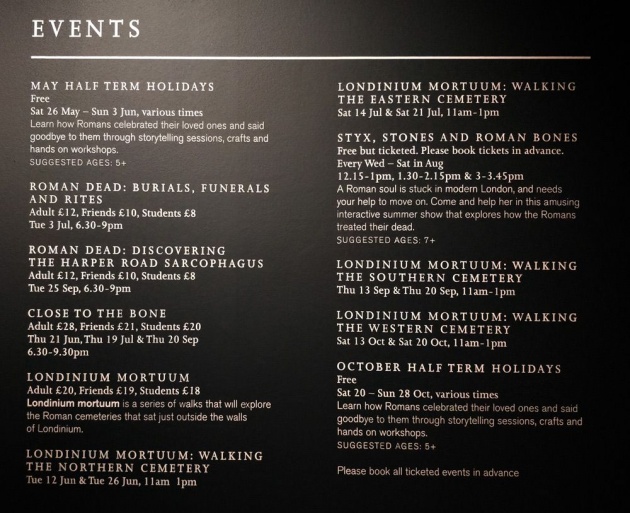

Other events

The museum is holding events on the Roman Dead theme throughout the summer and fall. If you're in London, or planning to go there at the time, they may be of interest.

The following picture includes the whole list of events:

Image credits: Events by Naotalba

I'm feeling quite partial towards the Styx, Stones and Roman Bones event. It looks fun, and I'll be on holidays at that time, so why not?