The evening of Thursday 1 December 1955 saw Rosa Park finish her day’s work as a seamstress at a department store in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, and walk to the bus stop. As an African American, Parks had to abide by strict rules of racial segregation, known as ‘Jim Crow’ laws, enforced throughout the American South. On city buses, the first 10 rows of seats were reserved for whites no matter how crowded the bus might be. And drivers had the power to order blacks sitting toward the back of the bus to give up their seats for whites.

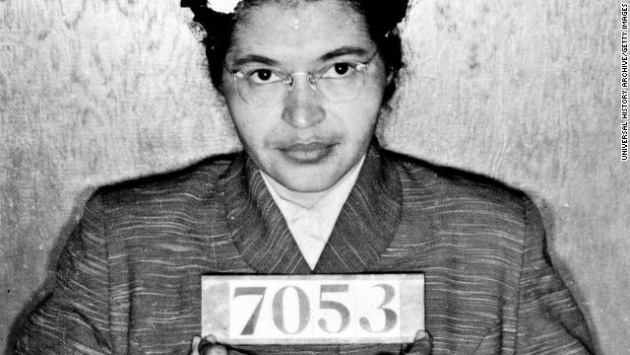

Parks, a well-educated 42-year-old woman, boarded the bus and sat down just behind the whites-only section. She watched as the vehicle filled up until no more seats were available. When a white man then boarded and stood in the aisle, the driver demanded that all four black passengers in her row give up their seats. Reluctantly, three of them did as they were told. But Parks did not move. It was n’t because she was tired, she later recalled, but because she “was tired of giving in”. Having watched blacks suffer daily indignities on Montgomery’s buses for years, Parks had made up her mind long before that evening: if she was asked again to relinquish her seat for a white person, she would refuse. She was arrested and charged with violating segregation laws.

It was n’t the first time a black passenger had suffered such a fate. But this time the incident triggered a vigorous response from black leaders, who called for a one-day bus boycott to demand better treatment. They did n’t know it at the time, but the Montgomery Bus Boycott would last 381 days and start a new chapter in the struggle for black equality in the United States. Although the boycott did not directly bring about desegregation – that could only be achieved in the courts – it was the first time southern blacks had mobilized enormous masses effectively to fight Jim Crow laws. Indeed, by providing the blueprint for non-violent action across the South, and placing a charismatic young preacher called Dr Martin Luther King Jr in the national spotlight, the Montgomery Bus Boycott gave rise to the African American Civil Rights movement.

TAKING A STAND:

Montgomery’s black citizens had been growing increasingly angry about their treatment on the city’s buses for years. It was n’t just segregated seating. Black passengers often suffered verbal abuse and physical threats. In 1949, for example, Jo Ann Robinson, a teacher who had recently joined the local Women’s Political Council, stumbled o the bus in tears after the driver had drawn his arm back as if to strike her for sitting in the whites-only section.

In 1953, Robinson was among black leaders who met with city socials to demand better seating arrangements and treatment. As a result, the mayor instructed the bus company to stop at every corner in black neighborhoods. But that was the only concession. A year later, the US Supreme Court ruled that segregation in the nation’s public schools was unconstitutional. The decision had no bearing on the bus situation, but it moved Robinson to write to Montgomery’s white mayor, William ‘Tacky’ Gayle. For the first time, she mentioned the possibility of a bus boycott.

Meanwhile, several black riders had been convicted for sitting in seats reserved for whites. In March 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat in the black section even when police arrived. Colvin was dragged from the bus kicking and screaming, and charged not only with violating segregation laws, but also assault and battery for resisting arrest.

Edgar D Nixon, founder of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Fred Gray, one of two black lawyers in the city, had been waiting for an opportunity to take the issue of bus segregation to federal court. They hoped to show that segregated buses were illegal under the US constitution. But they needed an ideal test case – someone who could withstand intense scrutiny. They considered Colvin but decided she was too young and too unpredictable. Two months later, Nixon and Gray found the perfect standard bearer when Rosa Parks, a softly spoken woman who was already involved in Civil Rights work, was arrested.

Parks agreed to fight the charges, even though she knew it might put her family in danger. at same night, across the city, Jo Ann Robinson and friends were printing thousands of leaflets calling on the black community to stage a one-day bus boycott the following Monday, the day of Parks’s trial. Over the weekend, black preachers called on their congregations to support the protest.

Still, it was a big ask. Most African-Americans could not afford a car, so how would they get to work? Even worse, they would face intimidation and violence. is was the land of the Ku Klux Klan, who thought nothing of terrorizing, beating or even murdering blacks who dared challenge segregation.

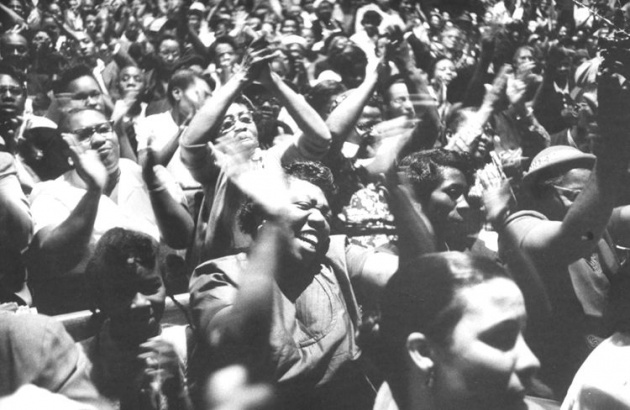

The black citizens of Montgomery were ready, though. And on Monday 5 December 1955, the city’s buses were empty but for a few white passengers. The boycott had begun.

TO BE CONTINUED...

ROSA PARKS (Part 1)

Posted on at