Rudyard Kipling was right about many things. But he was wrong when he wrote his famous line in The Ballad of East and West that “East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” I know he was wrong because I’ve seen the two meet many times. And this time I saw East and West meet last Thursday at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

A famous Afghan Proverb from “Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs” is “Yak teer wa doo neshawn." In Dari it's یک تیر و دو نشان and it means "One shot and two targets." In English we say “To kill two birds with one stone.” But as with many Afghan Proverbs, the meaning is the same in both languages: two things for the price of one.

It was “Yak teer wa doo neshawn” last week when The George Washington University’s Afghan Student Association invited me to Washington, DC to sign books and give a talk on “The Making of Zarbul Masalha.”

Zarbul Masalha book talk sponsored by George Washington University's Afghan Student Association

The book talk and signing had been planned for some time. But by sheer luck, the Afghanistan National Institute of Music’s renowned Afghan Youth Orchestra was beginning their first-ever U.S. tour at the Kennedy Center the night before the Zarbul Masalha book event. I couldn’t miss such a milestone for Afghans and Afghanistan. The free concert at the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage on February 7 turned out to be so popular that the theater was standing room only. Fortunately, Zarbul Masalha’s new literary manager, Suzannah Simmons, was able to arrange advance tickets for the two of us and we got in with excellent seats.

I don’t know much about the details of making music. But I know what I like when I hear it. As Suzannah and I spoke with some young Afghan fans of Zarbul Masalha before the concert, I learned that Suzannah is classically trained in guitar, cello and piano – and studied music theory for a year at St John’s College. This was almost too good to be true. Foreign cultures and music are both languages that must be learned. I speak Dari (Afghan Farsi) and the language of Afghan culture. I had just learned that my literary manager speaks the language of music. So we could translate the two languages for each other.

I don’t know much about the details of making music. But I know what I like when I hear it. As Suzannah and I spoke with some young Afghan fans of Zarbul Masalha before the concert, I learned that Suzannah is classically trained in guitar, cello and piano – and studied music theory for a year at St John’s College. This was almost too good to be true. Foreign cultures and music are both languages that must be learned. I speak Dari (Afghan Farsi) and the language of Afghan culture. I had just learned that my literary manager speaks the language of music. So we could translate the two languages for each other.

The curtain rose, and the Afghan Youth Orchestra began bringing East and West together in a stunning performance of Antonio Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” with an absolutely unique blend of classical Western and Afghan instruments.

The following is a conversation between “Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs” author Edward Zellem and Suzannah Simmons of StrengthN Communications. The forum is the Kennedy Center and the crossroads of Afghan culture with one of the West’s best-known symphony masterworks - Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons.”

----------

Edward Zellem: What a fantastic musical experience. Suzannah, let’s talk about the Afghan Youth Orchestra’s performance of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons from two different angles - Afghan culture and western classical music theory. I don’t know much about music theory, but I do know that Vivaldi wrote The Four Seasons in four parts. He titled them “Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter.”

Suzannah Latané Simmons: Edward, it is truly a pleasure and honor to have the opportunity to discuss this compelling performance with you, as you have combined East and West in your own life and have quite a working knowledge of Afghan culture!

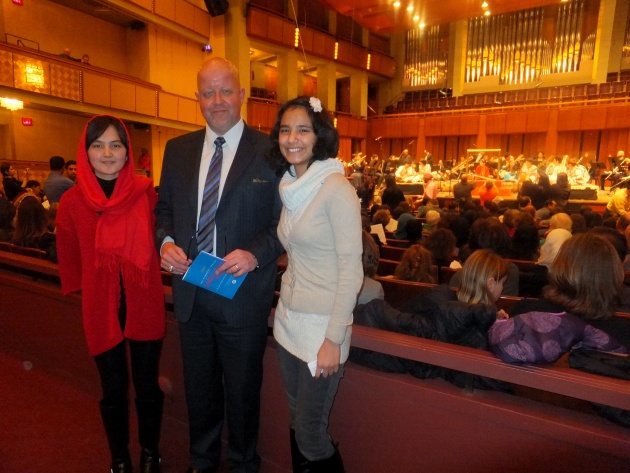

With Afghan Proverbs fans Mahsheed and Fatima

You are correct that Antonio Vivaldi’s most famous work is broken into four parts. Specifically, they are referred to as concertos. Within each concerto, there are three movements whose rhythms are fast, slow, fast, respectively. Each concerto in The Four Seasons is different and symbolizes Earth’s seasons. The impact of the performance is in using specific rhythms, harmonies, and pitches to evoke feelings and images that reflect each season. Vivaldi's original arrangement for The Four Seasons was with a solo violin, string quartet, and bass.

What is interesting about the Afghan Youth Orchestra’s performance of The Four Seasons is not only that it has combined the sounds of East and West, but it has also brought in the unique culture and instruments of Afghanistan. Specifically, we hear violin, cello, viola, oboe, trumpet, xylophone, and guitar (Western instruments) impactfully combining with the rubab (string), sitar (string), ghichak (string), tanbur (string), tabla (percussion), dhol (percussion), dilruba (string), and sarod (string). This is the first time I have seen such a beautiful marriage of such different instruments.  Afghan Youth Orchestra musician with rubab

Afghan Youth Orchestra musician with rubab

EZ: So in the first movement of The Four Seasons, the Afghan Youth Orchestra re-imagined Vivaldi’s Spring concerto at a Nowruz (Persian New Year) festival in the Bagh-e Babur (Garden of Babur), and at the ruins of former King Amanullah’s Darul Aman Palace. Both are in Kabul and I’ve visited each of them several times. So I was very moved by the musical representation of them. The orchestra's rendition of Spring also reminded me of the Afghan Proverb, “Ba yak gul bahaar na-meysha” به یک گل، بهار نمیشه (One flower doesn’t bring spring). How did they do that musically, and with what instruments?

SLS: Let me try to explain how the instruments invoked the feelings of not only spring, but also the celebration of the Persian New Year in Afghanistan. The trumpet announces the arrival of the season, but it is the solo plucking of the Afghan string instruments that creates the sound of birds. Moreover, the eastern tone of the Afghan instruments mentioned above brings us out of the West and into an Eastern sentiment. Additionally, the rhythm of the concerto starts out slowly, but builds just as we see a few blossoms at the beginning of spring exploding towards the end of the season. Thus, the original 12/8 rhythm of the concerto becomes a fast 7/8 or Afghan “mughuli” rhythm which turns into an even faster 8/8 rhythm with the rubab and sitar.

EZ: I loved what they did with Vivaldi’s second concerto, Summer. It was fast-paced and stirring as they represented the weather of an Afghan summer.

SLS: I agree! The first movement of the concerto felt like the heat of summer, as I am sure you can relate to after living in Afghanistan. The xylophone, clarinet, and ghichak ominously warn of what I imagine is the typical summer storm. For the second movement, the strings of the sitar playing a static melody give a sense of the calm before the storm while the guitar interruptions mimic thunder. Again as in all four concertos of The Four Seasons the first movement is fast, the second movement is slow, and the last movement is fast. We feel the calm before the storm in the second movement of “Summer", with the actual onset of the storm in the third movement. The third movement's solo performances of the rubab and sarod gave a lot of weight to the storm, and were complemented by the powerful interjections from the orchestra.

A buzkashi game

EZ: My favorite part of the performance was when they played the last movement of the “Autumn” concerto to evoke a buzkashi game in Afghanistan. I’ve seen buzkashi played live. It’s a thrilling, fierce, high-speed game played on horseback. It’s somewhat like the game of polo, but is far rougher and uses a headless goat carcass instead of a ball. It’s the Afghan national sport - wild, very traditional and famous. Suzannah, can you explain how the Afghan Youth Orchestra played a buzkashi game musically with Vivaldi? Amazing.

SLS: Well, the Buzkashi game was musically translated by the trumpet, violins, cello, sarod, rubab, and ghichak. The trumpet announces the start of the game, with the Afghan instruments then picking up speed and playing elements of a traditional song called “Katagani” that Afghans associate with buzkashi. The sarod and rubab volley back and forth like Afghan horsemen competing in the game. However, there is a symbolic winner in the sound of the ghichak. Very appropriately, the ghichak is a native Afghan instrument. To celebrate the winner, the National Anthem of Afghanistan, “Surud-e Milli,” closes the third movement of Autumn. What a victorious end to a spirited and lively “game!”

The Four Seasons ends with the final movement of the Winter concerto, re-imagined as Salaam (Peace)

EZ: And then the Afghan Youth Orchestra finished The Four Seasons with the Winter concerto. I especially liked the first movement’s musical representation of Badakhshan, an isolated province in Afghanistan’s high northeast. Then they segued into a beautiful rendition of Winter’s second movement that they have renamed “Khanna” (home). What are your thoughts on how they played those?

SLS: The ghichak was the perfect instrument to start Badakhshan, the first movement of Winter. Consisting of only two strings, when plucked alone the ghichak can sound cold and icy. As winter can feel isolating and lonely, having a solo for Khanna (the second movement) was a great choice. Not only was the solo performed with emotion and talent, but the juxtaposition of one of the youngest members carrying out the solo was moving and heartfelt. In closing Khanna, the tempo speeds up and the whole orchestra joins in. Winter doesn’t feel lonely anymore. Poignantly, the last and final movement, Salaam (Peace) is closed by the sounds of the rubab, the national instrument of Afghanistan. It’s an instrument with a 2000-year-old history.

Afghan Youth Orchestra musicians with sitars

EZ: Suzannah, thanks so much for helping me interpret the language of music and what happens when two musical languages and cultures meet. It was one of the most memorable concerts I’ve ever seen. I thought it showed the tremendous value of interpreting one culture’s musical tradition through the lens of another culture’s tradition. Both sides benefit and expand their musical horizons.

Kipling’s “twain” CAN in fact meet, and East and West can raise each other to a new level, if both sides cooperate and are open to each other. I think that’s a powerful metaphor for what the future of Afghanistan can and should be. As the Afghan Proverb says, “Dil ba dil raah darad.” دل به دل راه دارد (Heart to heart there is a way). Any final thoughts?

SLS: Thank you for choosing me to join you! I have so many thoughts from this inspiring performance. I think about these Afghan children. Although they come from a beautiful country, they have lived through tremendous tragedy, poverty, and war. Despite this, they play their instruments with focus and peace. It brought tears to my eyes to feel the power of their music, witness the dedication of their work, and hear their notes playing in friendly harmony with a few young adults and children from the Maryland Classic Youth Orchestras.

I hope that the Afghan Youth Orchestra’s U.S. tour will help bring more compassion and awareness for the positive side and the warm culture and people of Afghanistan, and that it will help motivate Americans to continue to reach out and help this amazing country and its people.

Twitter: @afghansayings

More of Edward Zellem's interviews with Afghan celebrities and thought leaders are coming soon.

More of Edward Zellem's interviews with Afghan celebrities and thought leaders are coming soon.

To be notified of new interviews, updates and articles, please visit here and click the green "Subscribe" button.