Senegal prepared Monday to begin the trial of former Chadian dictator Hissene Habre, 25 years after he fled there following an eight-year bloodsoaked reign of terror at home.

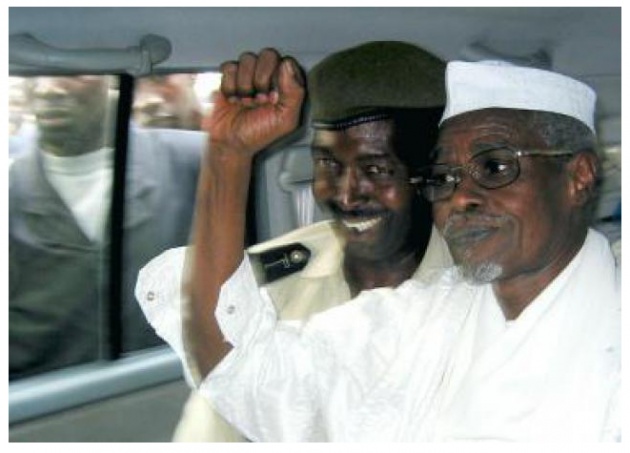

Once dubbed “Africa’s Pinochet”, the 72-year-old has been in custody in Senegal since his arrest in June 2013 at the home he shared in an affluent suburb of Dakar with his wife and children.

Rights groups say 40,000 Chadians were killed between 1982 and 1990 under a regime propped up by fierce crackdowns on opponents and the targeting of rival ethnic groups he perceived as a threat to his stranglehold on the central African nation.

Delayed for years by Senegal, the trial will set a historic precedent as until now African leaders accused of atrocities have been tried in international courts.

Senegal and the African Union signed an agreement in December 2012 to set up a court to bring Habre to justice.

The AU had mandated Senegal to try Habre in July 2006, but the country stalled the process for years under former president Abdoulaye Wade, who was defeated in 2012 elections.

Habre was also wanted for trial in Belgium on war crimes and crimes against humanity charges after three Belgian nationals of Chadian origin filed a suit in 2000 for arbitrary arrest, mass murder and torture.

Macky Sall, Wade’s successor who took office in April 2012, ruled out extraditing Habre to Belgium, vowing to organise a trial in Senegal.

“This is the first case anywhere in the world—not just in Africa—where the courts of one country, Senegal, are prosecuting the former leader of another, Chad, for alleged human rights crimes,” Reed Brody, a lawyer at Human Rights Watch (HRW) told AFP.

Justice in Africa

Brody said it was also the first time that the concept of “universal jurisdiction”—that a suspect can be prosecuted for their past crimes wherever in the world they find themselves—had been implemented in Africa.

“So there are a lot of historical aspects to this. But, for me, the most important kind of thing is that it is the survivors who have pushed for 25 years,” he added.

Habre will be judged by the Extraordinary African Chambers, set up by Senegal and the African Union in February 2013 to prosecute the “person or persons” most responsible for international crimes committed in Chad during Habre’s rule.

The trial will be heard by two Senegalese judges and one from Burkina Faso, who will serve as president of the process.

The chambers indicted Habre in July 2013 and placed him in pre-trial custody while four investigating judges spent 19 months interviewing some 2,500 witnesses and victims and analysing thousands of documents.

Around 100 witnesses will testify during hearings expected to last around three months, although 4,000 people have been registered as victims in the case.

Habre has said he does recognise the court’s jurisdiction and vowed that he and his lawyers will play no part, although under Senegalese law he could still be forced to turn up.

“When we began this case, when we started working with the victims—I stated in 1999 -- one of the victims said to Human Rights Watch ‘since when has justice come all the way to Chad?’,” Brody told AFP.

“The African Union saw the importance of being able to show that you can have justice in Africa,” he added.