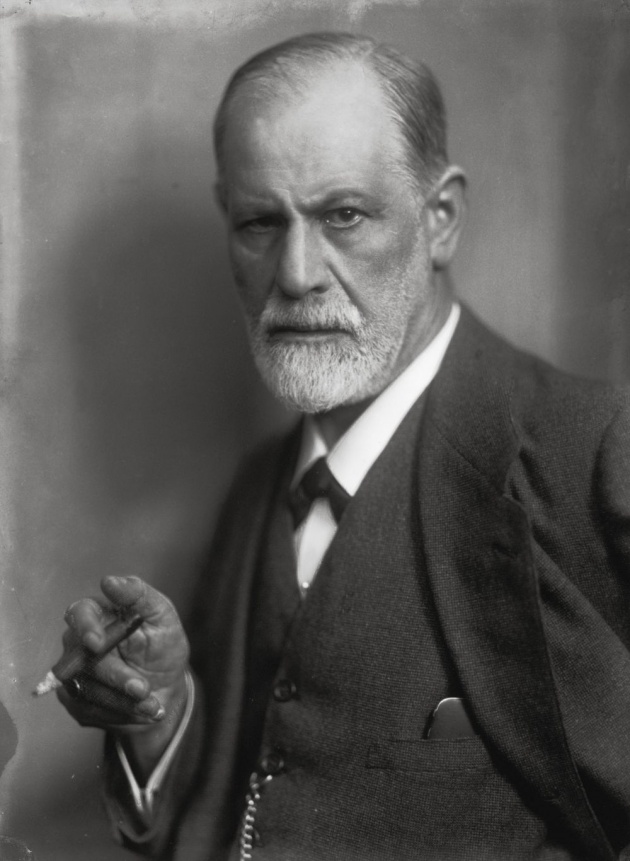

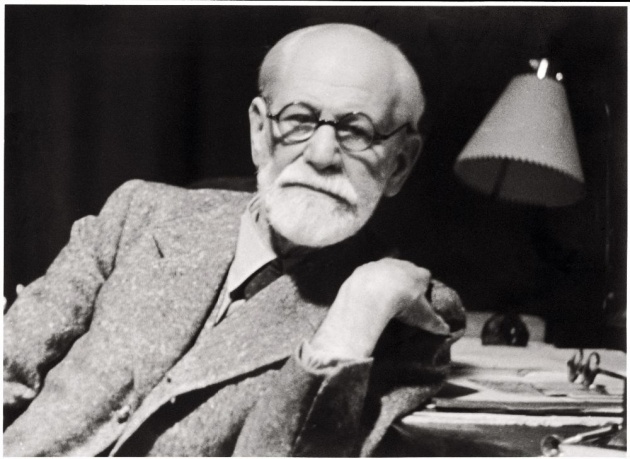

It was also around this time that Freud appeared to give up what had been a 12-year-long cocaine addiction, having extolled the virtues of the drug – “a magical substance” – in 1884 in a paper called ‘Uber Coca.’ Curiously, this was also the year that Freud’s father died. Around three decades later he himself underwent treatment for an array of psychosomatic disorders where he came to realize the strong hostility he had felt towards his father. Freud later wrote that, “the study on coca was an allotrion” (an idle pursuit that distracts from more serious responsibilities).

During this self-analysis, he also confirmed that he recalled childhood sexual feelings for his mother, seemingly giving credence to his controversial Oedipal theory, which he began exploring in 1897. Freud initially seemed obsessed with the idea that most of his patients had suffered sexual trauma at some point in their lives – and those who were reluctant to talk about this alleged abuse were displaying signs of ‘resistance.’ He later changed his mind (as he was liable to do) and decided that, in fact, these were just fantasies – ‘infantile wishes’ as described in his notorious Oedipus theory. The gist of that theory is that young boys harbor repressed desires to possess their mothers and replace their fathers, while girls feel desire for their fathers and jealousy toward their mothers. This is compounded by the boy’s alleged castration anxiety, and the girl’s supposed penis envy.

It’s surprising this theory did n’t meet more opposition, and Freud could count some of society’s most respectable figures among his followers, giving him authority with the masses. Marie Bonaparte (a great-grand-niece of Napoleon), for example, helped to establish his theories in France. It seems that at some point she gave serious consideration to sleeping with her son and wrote to Freud for his advice. “It’s not always harmful,” he replied. Although whether that was his true belief, or he was driven by a desire to keep a wealthy and influential follower happy, is up for debate.

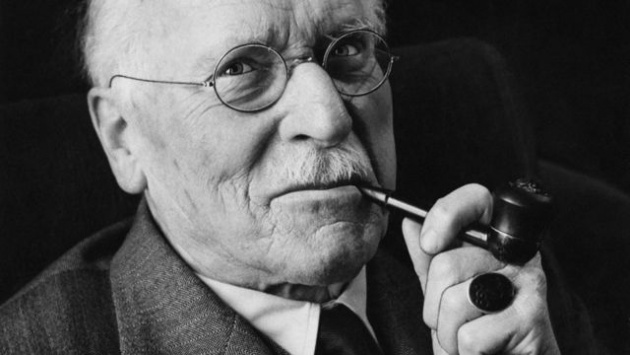

Nonetheless, Freud’s work had attracted the attention of the wider psychology community, and in 1906 psychologist Carl Jung reached out to Freud when he found his word association tests provided evidence for Freud’s theory of repression. The pair met a year later and allegedly talked for 13 hours straight. Theirs was a tricky relationship, though, with Jung once writing to Freud: “Let me enjoy your friendship not as one between equals, but as that of father and son”, which caused alarm for the elder psychologist whose theories orbited around the sinister Oedipal theory.

Despite another wise fulfilling relationship, tensions between Jung and Freud persisted. Jung believed Freud’s theories to be too reductionist, and was unable to accept that the main drive in life was sexual. Freud was dismissive of Jung’s broader approach, and skeptical of his interest in paranormal and psychic phenomena, while Jung was troubled by the thought that Freud placed his personal authority above the quest for truth. It was clear that Freud had little tolerance for colleagues who diverged from his psychoanalytic doctrines, and in 1913 the relationship between the two came to an end. This stubbornness was also apparent in his attitudes toward religion; Freud allegedly forbade his Jewish wife Martha from lighting candles on the Sabbath, claiming religion was “mere superstition.”

Objectively, it would be easy to dismiss Freud as something of a quack. Speculation abounds that he fudged his experiments, his data was drawn from a small group of Viennese women and his own ‘self-analysis’ and, perhaps most crucially, none of his theories were ever peer reviewed – nor could they be, since his methodology rested on speculation and subjective insights. He tapped into the huge attraction of a theory that promised every individual the key to their own hidden secrets, not to mention, for the first time ever, a theory of human nature, and at the center of his work was the most intriguing and thrilling of all taboos: SEX. As Karl Kraus put it many years ago, psychoanalysis itself became the poison it purports to cure.

While many of his more questionable theories have been widely discredited, Freud’s work has nonetheless played a crucial role in our understanding of the human mind. While he did n’t invent the concept of the ‘unconsciousness’, he did bring its importance to the fore, and had Freud been around today he would likely take great interest in the work of contemporary neuroscience, since it provides compelling evidence for unconscious mental processing.

Unorthodox as his ideas were, Freud has been recognised as a catalyst for a greater curiosity about the nature of human personality – something even he couldn’t fully master. In 1939, he died of cancer, having been unable to gain control of his tobacco smoking – a typical ‘oral fixation’, the theory of which, ironically, formed the cornerstone of his life’s work.

SIGMUND FREUD (The Man Who Changed The Face Of Modern Psychology) (Part 2)

Posted on at