Moawia Eldeeb grew up with his family on a village farm bordering the Nile, growing rice in the summers and vegetables in the winters. It was the way things had been for years, decades even.

But when Eldeeb’s brother was born with a rare genetic condition called ectodermal dysplasia, everything changed immediately. Because of the condition, Eldeeb’s infant brother couldn’t sweat. And given Egypt’s humid climate, this meant a certain and swift death.

His father, who had been applying every year for a green card for the past 15 years, fortunately had won one in the lottery. Roughly two weeks after Eldeeb’s brother was born, they left everything they had ever known behind.

“We had no option but to move right away. We knew we had to come to the U.S.,” he said. “We went to New York and we were like, let’s figure life out.”

In the beginning, Eldeeb went to school for a few weeks. But the family needed money, so he started working 12-hour shifts at a pizza shop to earn about $20 a day in Astoria, Queens. During the New York’s sweltering summers, they all took turns giving his little brother constant showers.

Eldeeb working in a Queens pizza shop as a child shortly after immigrating to the U.S.

“We couldn’t even make rent and my dad had a hard time finding work,” Eldeeb said. They had to return to Egypt briefly for a year before coming back again.

The work shifts kept Eldeeb from attending middle school regularly.

Then, in high school, bad luck hit again. The house his family was living in burned down after a repairman, who was smoking a cigarette while fixing the boiler, accidentally instigated a massive explosion and fire. They ended up in a Red Cross shelter.

This is where things could have gone from bad to worse. But there were benefits from being in a shelter.

For the first time in a long time, the family didn’t have to worry about rent. Food stamps were paying for things to eat. And Eldeeb could start to think about other things like school.

He started going to a free gym in Harlem. He was a scrawny kid from Queens, but others took him under their wing and taught him how to lift and work out.

“People motivated me and encouraged me,” he said. “That was the first time I felt like I was getting better. It was the first time I felt like I was achieving anything in life.”

He started to catch up on school by watching Khan Academy videos. He said he finished every video that was available at the time, and then started going to Saturday and Sunday school on the side.

He finished 11th and 12th grade in a single year, then went to Queens College and got an applied math degree in 2 1/2 years. He heard about a transfer program to Columbia and made the switch to study computer science. Along the way, he also went throughCoalition 4 Queens, a non-profit that Google and Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian recently backed to teach low-income residents of Queens how to code.

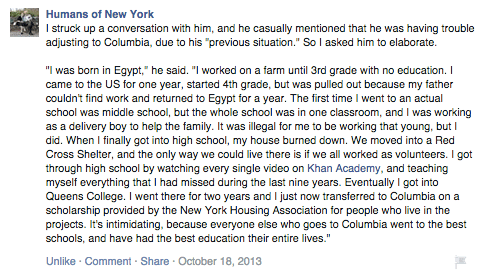

Columbia was intimidating at first. That fall, Humans of New York photographer Brandon Stanton, caught Eldeeb in the subway and took the photo below.

A lot of his classmates had no idea about Eldeeb’s past. But once that Humans of New York photo went viral, they began to help him out.

Throughout his entire time in college, Eldeeb would work as a personal trainer, using the skills he learned in that Harlem gym to coach others and make extra money.

In Columbia’s computer science program, Eldeeb would also end up meeting his co-founder Joshua Augustin, who was studying computer vision.

Because personal training had been so transformative for Eldeeb, he wanted to figure out a way to make it more accessible to everyone else. In big cities like New York and San Francisco, trainers can cost $100 or more an hour. It’s prohibitively expensive.

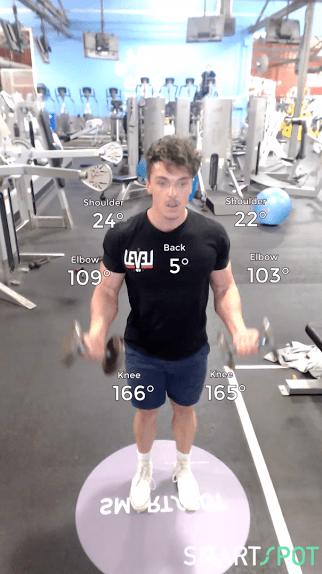

Using Augustin’s computer vision talents, they built a set-up that mixes a Kinect camera and a large flatscreen TV. It records your work out and can point out when your angles are off or if your posture is misaligned. It also has timers so you can track and control how long you rest between reps.

More importantly, Smartspot keeps video logs so that if you want a personal trainer to review your progress, you can do it more affordably. Personal training, like hair cuts, is a non-tradable service. That means you have to find a provider where you are, and your schedule has to align with theirs.

From a practical level, this means that personal trainers have to charge high hourly rates during peak times after work in order to compensate for the lack of work during the middle of the day.

With Smartspot’s systems, Eldeeb and Augustin think that this would make it easier for people to rely on trainers from other parts of the country or even the world to review their progress, correct their technique and motivate them. (Kind of like how another YC-backed company 7 Cups of Tea allows anyone to seek online counseling or therapy from anywhere.)

They sell the equipment for $2,500 to gyms. Gym members can use it for free, but if they want additional personal training, they can pay a fraction of the cost of a normal personal trainer to have one review their workouts and coach them on technique.

At the Potrero Hill gym I met the pair at, about 60 percent of the membership had used Smartspot.

“When I was a personal trainer, I could see how almost everyone else in the gym was doing the exercises wrong. They couldn’t afford a trainer, and the whole dream here is to make training more affordable to the American population.”

The pair are demo-ing Smartspot at Y Combinator today. Eldeeb’s parents don’t really have any idea what Y Combinator is, nor did they know what Columbia University was.

“My dad has been supportive of me with exercise my whole life,” Eldeeb said. “Even though he has no idea what I’m doing right now or how to make a company in America, he believed that I could go do it.”