The previous blog was a summary of the first section of Chapter Eight in Richard Walter’s “Essentials of Screenwriting” focusing on character development in screenwriting; this blog is a summary of the next section which focuses on the importance of evoking a sympathetic audience for characters in screenwriting.

In this section, Walter discusses how to construct a character in a script that captures the sympathy of the audience through several examples. The fundamental principle to evoke sentiments of understanding and pity in the audience is to make the character relate to the audience in some way. In Treasure Island (Lawrence Edward Watkin, adapting the Robert Louis Stevenson Book), the antagonist, Long John Silver, is portrayed as a wicked, peg-legged old man who holds the protagonist, young Jim Hawkins, hostage and threatens his life; however this side of the villain is compromised when British sailors find him and pursue him as he desperately struggles to escape from the shore in a dinghy, pitifully slipping on his wooden leg in the sand as he attempts to launch it. At the end, he does escape with Hawkins’ help, much to the audience’s delight; as Walter puts it, “[this] provides [the audience] with a glimmer of hope for our own undeserved salvation”. The connection mentioned here, between the audience’s own desires and interests and Silver’s act of surrendering his wickedness as well as his deliverance from punishment, encourages understanding and tolerance in the audience. Walter lists many other examples in which characters captivate the compassion of the audience through similar methods; he also provides examples that illuminate the importance of such characters.

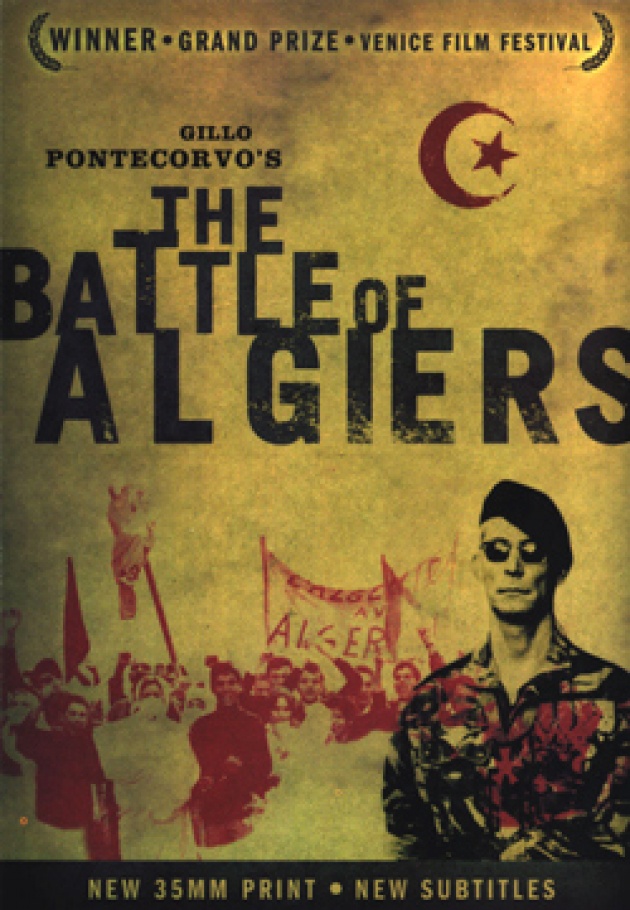

Walter provides a wealth of historical and current evidence shedding light on the importance of characters that encourage pity or understanding in the audience. As far back as the ancient Greek era characters that attracted a sympathetic audience were desirable and significant playwrights went to great lengths to create these characters. Sophocles, for instance, constructed Oedipus as a protagonist who kills his father and commits incest but is unaware of his origins until after he has committed the associated crimes, evoking pity and sympathy in the audience. A comparison between modern day Z (Jorge Semprún, adapting the Vassili Vassilikos novel) and The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, Franco Solinas) demonstrates that the sought after characters in ancient theatre are very much the same as today’s desired characters in screenwriting. The Battle of Algiers is the superior of the two because the characters command, to varying degrees, the understanding of the audience by portraying the villains, the French establishment, as being not born evil but the product of their upbringing and the protagonists, the Algerian independence fighters, as being imperfect heroes who commit such blunders as murdering innocent children. Each of the examples Walter delivers, some that are not mentioned here, adds further merit to characters that inspire a sympathetic audience in screenwriting.

Essentially, Walter describes how characters’ behaviour evokes sympathy in the audience in screenwriting and provides examples illustrating the importance of these characters. The next blog will be a summary of the last major point he discusses in relation to characters in screenwriting, that is, the necessity of avoiding stereotypes.

Written by Amelia Nakone