By the mid-20th century, with footprints left across even the most inhospitable polar regions, many people believed that there was nothing left to discover on Earth. Humans would soon start looking beyond our own planet for new worlds to explore – yet one vast patch on the terrestrial world map remained blank: an immense sea of sand rolling across 250,000 square miles of the southern Arabian Peninsula.

In Arabic, this region is known as Rub‘ al Khali: the ‘Empty Quarter’, sprawling across swathes of modern-day Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Hardy Bedouin tribespeople are its only habitual inhabitants, but somewhere within its enormity, a great metropolis once thrived – the fabled lost city of Ubar, dubbed the ‘Atlantis of the Sands’ by TE Lawrence. At the end of World War II, virtually nothing was known about the Empty Quarter – something that an eccentric English explorer set out to put right.

SON OF THE DESERT:

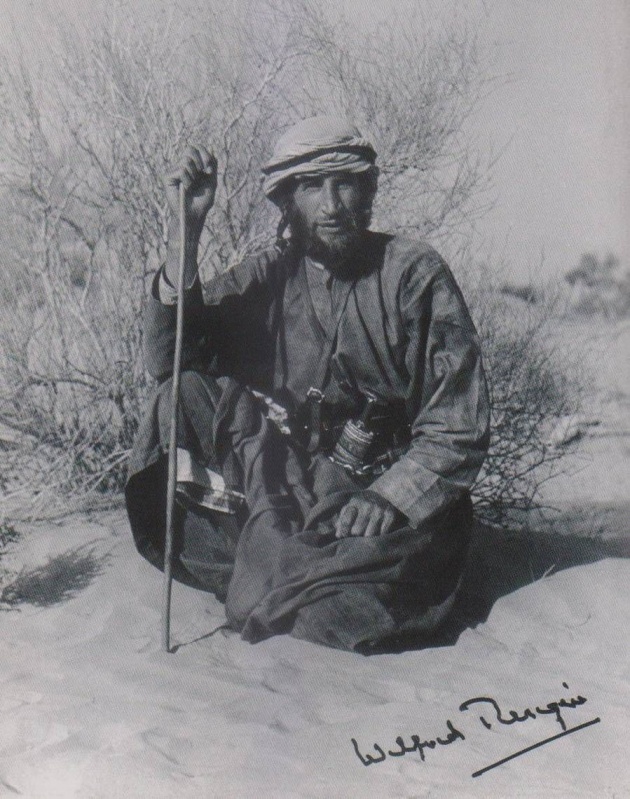

Wilfred Thesiger was born in Ethiopia in 1910, the son of a British diplomat, and spent his early childhood in Africa. Ostensibly the archetypal product of Imperial England’s tweed-clad class, he attended Eton and Oxford, where he earned his Blue as a champion boxer. A noted big-game hunter, he was decorated for bravery during a military career that included a stint with the SAS.

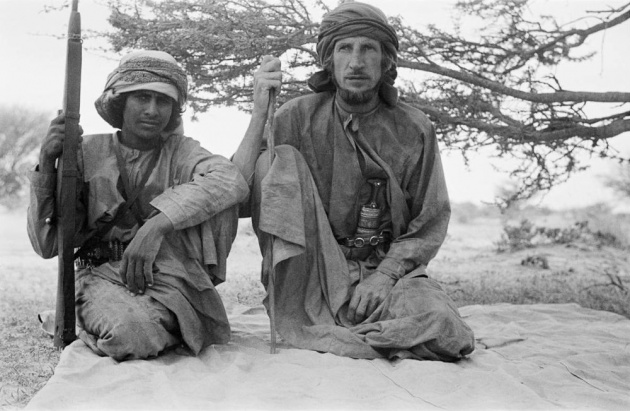

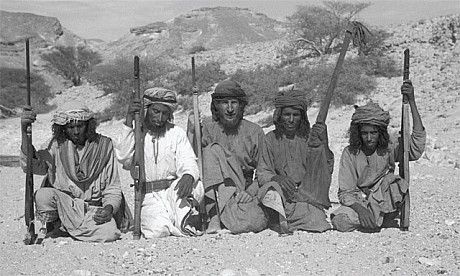

Despite his privileged background, Thesiger’s adult existence was a life less ordinary, largely spent in uncomfortable conditions. He spurned Western society, preferring the company of indigenous guides wherever he was exploring. His adventures took him to live with the Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq, documenting a community that has since been annihilated. He also travelled through Iran, Kurdistan, French West Africa and Pakistan, and lived in northern Kenya, but it’s for his Arabian exploits that he is most remembered – in particular, his double traverse of the Empty Quarter.

Though he did n’t start writing for publication until late in life, and even then with reluctance, he’s regarded as a pioneer of experiential travel journalism. Thesiger’s image collection is an invaluable record of traditional lifestyles that have since become endangered or extinct.

esiger wasn’t the first Westerner to cross Rub‘ al Khali. English civil servant and scientist Bertram Thomas traversed one part of the Empty Quarter during 1930-1, and author, explorer and sometime intelligence officer Harry St John Philby (father of the infamous double agent Kim Philby) traipsed across another in 1932, searching for Ubar, the legendary lost, frankincense-rich city of antiquity.

But it was esiger who first thoroughly explored this last, vast, sand-obscured spot on the world map – twice, in fact. And it was esiger who mapped the few features of this gritty wilderness, including Liwa Oasis (now in Abu Dhabi) and the quicksands of Umm as Samim in Oman.

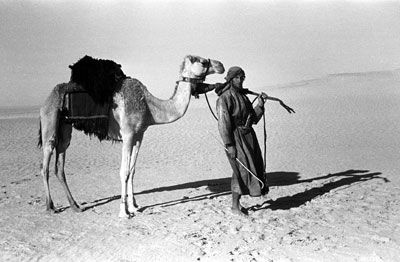

In 1945, the Middle East AntiLocust Unit (MEALU) hired Thesiger to search for locust breeding grounds throughout the region, essentially paying the explorer to roam around southern Arabia, accompanied by Bedouin tribesmen. On expedition, Thesiger travelled only by foot (barefoot, at that) or camel, constantly battling heart-breaking thirst, murderous raiding parties of bandits, quicksands, towering dunes, relentless exposure and the ever-present threat of starvation.

Thesiger undertook multiple trips in Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Oman, and on 25 October 1946, he left Oman’s southern port city of Salalah to attempt a camel crossing of the eastern sands of the Empty Quarter – something no Western explorer had done before.

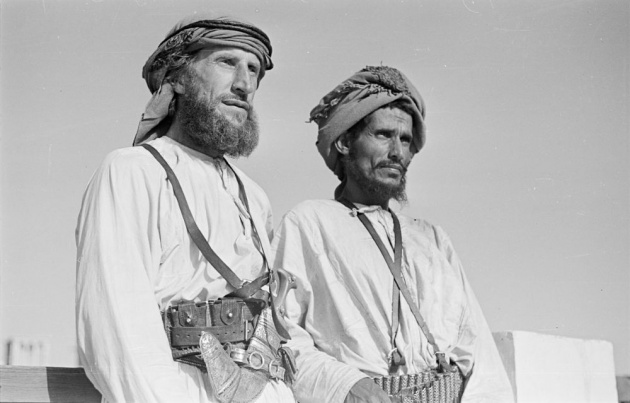

The region was trembling with tribal tensions, but Thesiger was accompanied by several Rashid and Bayt Kathir Bedouin, and had permission from the Wali (governor) of Salalah to travel as far as Mughshin Oasis at the desert’s southern edge. The party crossed the Qarra mountains and traced wadis (dry valleys) to the wells at Ma’ Shadid and Shisr. At the latter spot, Thesiger had secretly arranged a rendezvous with more Bedouin, with the intention of pushing on into the heart of the Empty Quarter.

At Mughshin, however, disaster struck: Mahsin bin Khuzai, leader of the Rashid Bedouin party, fell from his camel and broke his leg. Thesiger had to split the group, leaving the injured man with one contingent and continuing with the rest of the Bedouin into the Ghanim Sands. Thesiger and Sultan bin Ahmad, the leader of the Bayt Kathir Bedouin party, then had a dramatic disagreement. The senior Bedouin demanded the expedition turn around, but four of the party stayed with the Englishman.

Ascending the sand mountains of the ‘Uruq al Shaiba with their camels – the beasts driven to recalcitrance and rebellion by thirst, hunger and exhaustion – was the crux move of this eastern traverse. The party was desperately short of water and, if they failed to drag themselves across these monstrous dunes, almost certain death awaited. For several days, the Englishman lay on the brink of physical collapse, but the skilful Muhammad al Auf negotiated a route and the bedraggled group continued across the Suhul al Kidan and Al Batin sands.

Thesiger skirted the south of Liwa Oasis in mid-December, continuing through Abu Dhabi to reach the border at Wadi al ‘Ayn. Back in Oman, the expedition followed the stony wadis of the Ad Dhahirah and Ad Dakhiliyah regions. At Bai, Thesiger was reunited with the men he’d left behind to care for the injured Mahsin bin Khuzai. Together they crossed the stony desert, passing once more through the Qarra mountains and arriving back in Salalah on 23 February 1947.

A week later, Thesiger was on his camel again, travelling through southern Oman and Yemen. He completed one more trip for the locust-busters that year, to Saudi Arabia, but then ceased working for MEALU. Thereafter, he would bankroll his own expeditions.

ARABIAN FIGHTS:

By December 1947, the Empty Quarter was calling again. He was accompanied on his next expedition by Salim bin Kabina, along with his brother, two other Rashid Bedouin and a pair of Sa‘ar Bedouin guides. Tribal violence was still rife in this, the most desolate environment on Earth. The few oases that exist in the Empty Quarter had seen violent attacks from raiding parties on various groups, while the presence of an English infidel was seen as poisonous by many tribes. Thesiger’s inclusion of the Sa‘ar men was a calculated safety precaution, as members of that tribe had already stated that they would follow his party into the desert and slay them all. The region’s tribes knew Thesiger was in possession of money and good rifles, and two killing parties were also sent in pursuit of his group by a leader of the Dahm people.

Undeterred (and to some extent unaware), Thesiger attempted a western traverse of the Empty Quarter. It was only the speed at which they travelled that saved him from the chasing assassins. The party set off from Manwakh well in Yemen and travelled north-west across the sands of ‘Uruq az Zayza into Saudi Arabia – a huge risk, because the King, Ibn Saud, had already rejected Thesiger’s request to enter the country. Crossing Al Jaladah plain, they reached the Saudi government post of ‘Ayn al Hassi in mid-January. Yam men they encountered expressed hatred of Thesiger, as a Christian, and disgust for his companions.

Shorty afterwards, they were arrested by the Wali of Sulayyil, where Thesiger’s Bedouin guides were bound in chains. The Englishman fretted that their captors would chop off his companions’ hands, but fellow explorer St John Philby, a confidant of Ibn Saud, intervened. The King released them, granting permission for the expedition to proceed, with Philby joining them for a short time.

Thesiger continued north to Layla before crossing the Jawb al Badu to Jabrin Oasis. A harrowing journey to Dhiby Well followed, during which the group endured freezing conditions and constant life-threatening hunger. Negotiating the desolate saltflats of Sabkhat Mutti and passing through Al Dhafra, they eventually arrived in Al Batin sands, turning north from Liwa to reach the coast and Abu Dhabi on 14 March 1948.

BLACK GOLD:

It was here the irresistible black tide washing across the sands of Arabia first lapped the adventurer’s feet. Back in the Empty Quarter in 1946, Thesiger had lain, paralysed with hunger, on a sand dune for three days, experiencing hallucinations of motorised vehicles carrying him to safety. He’d decided then that he “would rather be here starving as I was than sitting in a chair, replete with food, listening to the wireless and dependent on cars to take me through Arabia”.

Yet, the man who opposed oil exploration, fearing it would destroy the Bedouin way of life he so admired, met executives from the Iraq Petroleum Company. He made no secret of his views but, ultimately, chose to work with them to finance his future expeditions.

So, in the end, the man who despised cars sold the information he’d collected and maps he’d made during his travels to the oil industry. In doing so, he helped these companies proceed on the path that would forever alter the face of his beloved Arabia.

WILFRED THESIGER (Exploring Arabia's Empty Quarter)

Posted on at